Posts tagged ‘movies’

Enjoy The Silence: 2013 Silent Film Festival

It’s July, the fog has swamped the city, and the Silent Film Festival (SFF) returns this week to San Francisco. Spanning an action-packed four days, the lineup includes classics, gems, and newly restored discoveries from locales around the world including Bali, Japan, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, England, Russia, and the United States. This year’s festival features legendary stars such as Louise Brooks (Prix de Beaute), Greta Garbo (The Joyless Street), Harold Lloyd (Safety Last!) and Douglas Fairbanks (The Half-Breed) and famed directors including G.W. Pabst and Yasujiro Ozu.

In contrast to the high-tone glamor found in the movies above, The House on Trubnaya Square is a sprightly little Soviet comedy that follows the misadventures of a cleaning lady in Moscow. As the cleaning lady rises through the ranks of the workers’ movement, the film satirically exposes the foibles of feudalism, capitalism, and socialism alike. As to be expected from the land of Eisenstein, the movie features great editing, along with excellent camerawork, choreography, and story structure, as well as a cheeky performance by Vera Maretskaya as the cleaning lady swept up in the social movements of the time.

Another notable program is the premiere of the recent restoration of The Last Edition, an entertaining yarn shot in San Francisco in 1924. The movie looks at corruption in the newspaper publishing business, in which an unscrupulous publisher takes advantage of an overly trusting pressman. The populist film sides with the workingman against the corrupt bosses, reflecting the sentiments of the Wobblies and other early 20th-century labor organizations. The movie is especially fun for its local flava, as much of it is shot at the Chronicle Building at 5th and Mission Street and concludes with an exciting chase through the streets of San Francisco, passing by recognizable landmarks including the newly rebuilt City Hall. The film also features huge mechanical presses, typesetting trays, switchboards and rotary phones, and other industrial age machinery that will gun the engines of your inner steampunk.

Also part of the festival is a presentation by John Canemaker on well-known newspaper cartoonist Winsor McKay that includes of illustrations from Canemaker’s bio on McKay as well as a screening of several of McKay’s brilliant animated films. Best known for his long-running comic strip Little Nemo, McKay’s animations are masterful, deft, and magical, ranging from the whimsical Little Nemo and Gertie the Dinosaur through the dramatic, realistic Sinking of the Lusitania. My personal favorite is How A Mosquito Operates, in which a prodigious bug repeatedly sinks its very sharp stinger into a sleeping man’s nose, its protuberant abdomen swelling with blood after each bite.

The Silent Film Festival is a rare opportunity to see these movies in all their big-screen glory, and it’s markedly more fun than watching DVDs by yourself at home. As per usual, all SFF screenings (at the gloriously appropriate Castro Theater) include live accompaniment.

San Francisco Silent Film Festival

July 18-21, 2013

Castro Theater

429 Castro Street (near the intersection of Castro and Market Street)

San Francisco, CA 94114

415-621-6120, castrotheatre.com

Blood Embrace: The Hitchcock 9 at the Castro Theater

Summer is nigh, and to whet your appetite for the upcoming Silent Film Festival (July 19-21), the Castro Theater and the SFF are showing the Hitchcock 9, the British Film Institute’s series of nine recently restored silent films by the master of suspense. While some are significant mostly to completists bent on viewing every film in Hitchcock’s oevre, the series also includes classics such as Blackmail and The Lodger, which are required viewing for British film followers, silent movie aficionados, and Hitchcock fanciers alike.

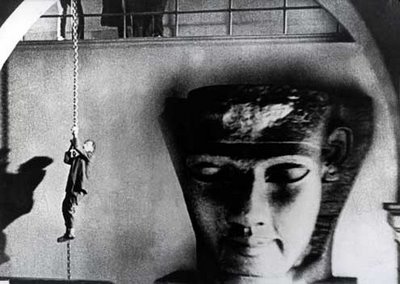

The series opens with the silent version of Blackmail (1929), which Hitchcock simultaneously directed as a talkie. Although Hitchcock had only began his directing career 1923, Blackmail is a fully formed Hitch film complete with transference of guilt, significant objects (knife and glove), expressionistic lighting, and a climactic chase scene at a landmark location, here the British Museum of Art, as well as the first of many Hitchcock cameos that would follow in his career. Demonstrating the director’s growing mastery of the cinematic language, the first half of the film has very few intertitles, as Hitchcock confidently reveals the narrative through evocative compositions and lighting, unusual camera angles, and other filmic devices. Every scene is a gem, utilizing vignetting, mirrors, shadows, and camera movement to underscore plot points or to emphasize a character’s state of mind. At one point, after the heroine has wandered the streets in a dazed fugue, she spies a neon sign that subliminally changes from a cartoon of cocktail shaker to silhouette of a stabbing knife. In another scene, Hitchcock tightly frames three pairs of hands in a pantomimed exchange, followed by a tilt up to the characters’ faces, thus underscoring the trio’s fraught relationship. The film’s climax at the museum includes an iconographic shot of a man descending a rope next to a huge sculptural face, presaging the Mount Rushmore chase scene in North By Northwest. It’s pretty impressive to see the progress in visual and thematic style between earlier films in the BFI series and Blackmail, as Hitchcock demonstrates that he was well on his way to mastering the cinematic form.

The Ring (1927) includes more early Hitch shenanigans. The story involves a love triangle between two pugilists and a carny girl and the film also includes familiar Hitchcock motifs such as the significant object, here a heart-shaped arm bracelet, plus lots of fun camerawork, double-exposures, and other tricksy manuevers that foreshadow Hitchcock’s later cinematic virtuosity. Set in the world of carnivals and circus people, the milieu recalls Hitchcock’s midcentury classic, Strangers On A Train, with its fascination for the macabre underbelly of the amusement park. Also illustrating a theme that would reappear in Hitchcock’s later work, The Ring explores the all-consuming power of lust, passion, and jealousy as the two rivals pound on each other in the boxing ring, thus externalizing their overwhelming desire for the female object of their affections.

The series also includes more obscure work such as the rom-com Champagne, and the Noel Coward adaptation, Easy Virtue. As is standard for Silent Film Festival presentations, all screenings will include live accompaniment.

June 14-16, 2013

Castro Theater

It Takes Two: 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival & San Francisco Global Vietnamese Film Festival

Spring has sprung and two film festivals are popping up this weekend here in the Bay, offering a bunch of Asian and Asian American films to pick from.

The 2013 edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival kicks off this week with a huge menu of movies from all over the planet. And the bienniel San Francisco Global Vietnamese Film Festival offers a more select but equally outstanding bill of fare.

I previewed a couple films that are a good indicator of the range and quality of the offerings this year at the SFIFF. Kenji Uchida’s Key Of Life is a fun and quirky, somewhat absurd comedy that follows a suicidal actor and a hitman who switch lives after the hitman loses his memory and the actor impulsively takes on his identity. Veteran actor Teruyuki Kagawa (Tokyo Sonata) is outstanding as Kondo, the confounded hitman, playing both bewildered amnesiac and serious-as-a-heart-attack assassin with equal conviction. Also fun is Ryoko Hirosue as Kanae, a nerdy girl desperately seeking a man to marry before her terminally ill father dies. Masako Sakai plays Sakurai, the suicidal actor who’s the third of the trio of main characters, as a hopeless slacker, yet one who rises to the occasion when in dire circumstances. Director Uchida, who’s an alumnus of San Francisco State’s Cinema Department, keeps the story briskly moving along and brings a droll touch to the twisty plot, but it’s the small details that really make this movie stand out, such as Kondo gamely donning Sakurai’s slightly too small, very nerdy clothes.

A wholly enjoyable movie to watch, Key Of Life is full of plot switchbacks that keep you guessing throughout, and the resolution of the three main characters’ various dilemmas is sweet, satisfying, and very funny. The movie is all about second chances and making the most of opportunities once life swerves from its expected route, and it’s one of the most pleasurable filmgoing experiences I’ve had in a while.

A very different kind of movie is Kalyanee Mam’s A River Changes Course, which won the World Cinema Documentary Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. Mam’s film is quite beautiful and moving in its examination of the corrosive effects of global capitalism on a rural Cambodia family. In the encroachment of what the farmers call “the companies,” or the multinational corporations that are buying and developing the land, the movie details a vicious cycle of forests cut or burned down, rice failing to grow due to drought, villagers contracting intestinal diseases from contaminated water, and the overfishing of the river, leading to families splitting up and the disruption of traditional ways of life.

No one smiles in this movie. After the farmers fall into debt from taking out loans to buy seed, women are forced to take factory jobs in the city sewing baby clothes for US$60 a month, and sons have to leave home to work for “the Chinese” in distant cassava fields. The film makes an strong statement about the destruction of lives and environments in Cambodia—lamenting the deforestation of the land one woman says, “We are not afraid of wild animals any more, we are afraid of people cutting down the forest.” Yet the movie does so with a delicate touch, never becoming polemical or preachy. Director Mam instead allows the grim faces of the displaced farmers and the tiny gestures of everyday life to tell the tale, as young kids endlessly gut and cut the heads off of dozens of small fish, small girls tote infant sisters to and from the fields, and endless rows of women in red bandannas bend over iron gray sewing machines in a garment factory.

The film doesn’t over-romanticize the hardships of village life, but it points out the difference between the villagers working for themselves versus toiling for “the companies,” and as such is an indictment of the destructive human cost of global capitalism’s implacable march.

Also this weekend is the San Francisco Global Vietnamese Film Festival at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco. A much more intimate affair than the SFIFF, the festival nonetheless includes outstanding work including Norwegian Wood, Tran Anh Hung’s adaptation of the popular Haruki Murakami novel, Tony Nguyen’s Enforcing The Silence, a documentary exploring the political rifts within the Vietnamese American community, and several short films including Viet Le’s “sexperimental music video” Love Bang!

San Francisco International Film Festival

April 25-May 9, 2013

various venues

tickets and schedule here

San Francisco Global Vietnamese Film Festival

April 26-28, 2013

Roxie Theater

3117 16th Street

San Francisco CA 94110

Sour Times: How To Survive A Plague film review

As I watched our President sworn in for his second term this week I was pleased to note that in his inauguration speech he gave a shout-out to the Stonewall riots and made encouraging noises about marriage equality. Though subtle and fleeting, it was a definite indicator of the mainstreaming of the LGBT movement.

This is especially evident after seeing David France’s stunning new documentary, How To Survive A Plague, which focuses on the early days of the AIDS crisis in the U.S. The contrast is stark between President Obama’s careful but inclusive mention of LGBT rights and the Reagan/Bush administration’s rampant homophobia and indifference to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 90s. France’s film specifically looks at the efforts of ACTUP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) in New York City as that grassroots organization sought to increase awareness of the epidemic and to pressure the government to develop treatments for the disease.

As one who lived through those times the film was very hard to watch in several spots, bringing back memories of the countless early deaths that devastated the gay community, here in San Francisco as well as in New York City and around the world. Though it’s very New York white middle-class male-centric (hello, Haiti?) it’s nonetheless a well-made and impressive piece of filmmaking. The documentary traces the stories of several young, mostly HIV-positive men who take up the struggle after the U.S. government fails to address the epidemic (then-President Ronald Reagan didn’t publicly utter the word “AIDS” until 1987, more than six years after the first case was diagnosed). The film follows several of these newly minted activists as they pressured the government, the medical establishment, and the pharmaceutical companies to search for effective treatments for AIDS.

The genesis of ACTUP coincided with the widespread use of the camcorder and the film is comprised primarily of historical camcorder footage interspersed with modern-day interviews. Although it took my digitally acclimated eye a little while to adjust to the unsharp VHS and Hi8 footage, the softer, fuzzier images are very evocative of the time and ultimately become a visual signifier for the era. Though not as crisp and clear as modern-day digital recordings, the footage is nonetheless powerful and moving as it documents seminal moments such as ACTUP’s infamous 1989 St. Patrick’s Cathedral “die-in,” the confrontation between ACTUP member Bob Rafsky and then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton (who gives as good as he gets, by the way), and the capping of extreme homophobe and all-around dickwad Senator Jesse Helms’ house in a massive canvas jimmy hat. The handheld, lo-fi quality emphasizes the immediacy of the footage and one archival sequence in particular, where dozens of protestors fling the ashes of loved ones who have died of AIDS onto the White House lawn, becomes astoundingly powerful in its intimacy.

Director France skillfully weaves together historical footage of the often-contentious ACTUP meetings (one featuring fire-breathing playwright Larry Kramer lambasting the bickering factions), various demonstrations, interventions, and acts of civil disobedience, and more personal footage of several significant participants, following them to their eventual fates. Sadly, for many including performance artist Ray Navarro, this means death from AIDS-related illnesses. After witnessing Navarro gleefully skewer the religious right as he performs as Jesus in early ACTUP demonstrations, it’s painful and poignant to watch his last days captured on video as he succumbs to blindness and delirium. The film follows other individuals who meet similar fates and, after watching video footage of them playing with their children at birthday parties or speaking out eloquently against ignorance and homophobia, their deaths are deeply felt losses. The film effectively captures the horror of the era as seemingly healthy young men are articulate and strong one day and are frail and dying of opportunistic infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma the next.

Some may argue that the movie is just another rehash of the ACTUP/Larry Kramer/New York City mythology that’s way too focused on a small group of gay white men to the exclusion of the rest of those affected by AIDS. To be fair, there are a couple women activists included (but their stories aren’t followed to the extent of the men in the movie), Latino artist and DIVA-TV member Ray Navarro has a featured role, and some of the b-roll includes images of African American men. Would the film have been a more inclusive and representative picture of the AIDS epidemic if there had more Haitians or females or people of color included? Sure. Would that make it a better, more powerful film? Not necessarily, it would just make it a different film. As it stands, the emotional and visceral impact is there, the craft is there, and the storytelling chops are there. Despite its somewhat narrow worldview, the movie makes a strong case for grassroots organizing and for standing up to institutional indifference, hostility, and outright discrimination, and for that it’s a significant and important piece of work.

I Want Candy: Hong Kong Cinema & the 3rd I South Asian Film Festival

This weekend the Bay’s got another embarrassment of filmi riches from a pair of dueling Asian film festivals. This year’s editions of Hong Kong Cinema, and the 3rd I South Asian Film Festival both offer a ton of tasty movie treats.

The 3rd I festival, which starts Sept. 18, runs six days and features over 20 films from 9 different countries including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, The Maldives, Canada, South Africa, UK and USA. Among the highlights is Jaagte Raho (Stay Awake), from 1956, starring my new favorite actor Raj Kapoor and co-directed by Amit Maitra and famous Bengali theater artist Sombhu Mitra. Jaagte Raho’s story follows Kapoor as a thirsty man from the country that arrives in the city longing for a drink of water. He ends up trapped in an apartment block where he’s mistaken for a thief, spending a long, sleepless night being relentlessly chased by the misguided tenants. As he hides out in various apartments he discovers the corruption and deceit amongst the residents, with adultery, gambling, drunkenness, counterfeiting, greed, and theft among their unsavory traits.

Although his earlier films featured him as an angsty young romantic lead, in Jaagte Raho Raj Kapoor iterates his naïf-in-the-big-city persona that he repeated many times in his later years. Here he’s all wide eyes and pleading gestures as the country bumpkin, a stark contrast to the duplicitous, licentious lot pursuing him.

This is great stuff, sly and satirical, that cleverly exposes the hypocrisy of the corrupt tenants. It’s shot in shimmering black and white with a crack soundtrack with lyrics by Shailendra and music by Salil Choudhary, including the rollicking drunken ramble Zindagi Khwaab Hai. The legendary Motilal is outstanding as an inebriated bourgeois who takes in the destitute Kapoor, in an homage of sorts to City Lights—however, Jaagte Raho’s booze-driven hospitality has a much more twisted outcome than does the Chaplin film. The film concludes with a lovely cameo by Nargis, once again representing the moral center of the movie. This was the final film to star Kapoor and Nargis and coincided with the breakup of their long-time offscreen affair as well, so it’s especially bittersweet to see the famous lovers together for the last time. Jaagte Raho was a box office flop when it was first released, but it’s since been recognized as a classic. Interestingly enough, along with Meer Nam Joker, which also bombed when it first came out, Kapoor cites this as his personal favorite film.

Also of note at the 3rd I festival: Decoding Deepak, a revealing look at the modern-day guru that’s directed by Chopra’s son Gotham; Runaway (Udhao), Amit Ashraf’s slick and stylish indictment of the link between politics and the underworld; Sket, which looks at a vengeful girl gang in an East London slum; the experimental documentaries Okul Nodi (Endless River) and I am Micro; this year’s Bollywood-at-the-Castro rom-com Cocktail; and the short film program Sikh I Am: Voices on Identity.

This year’s edition of Hong Kong Cinema, the San Francisco Film Society’s annual showcase of movies from the former Crown Colony, has a bunch of outstanding product. The program includes a three-film retrospective commemorating the 1997 handover: Peter Chan Ho-sun’s Comrades: Almost A Love Story, which stars Leon Lai and Maggie Cheung as friends almost with benefits from two different sides of the HK/China border; Made In Hong Kong, Fruit Chan’s debut that’s a redux of the venerable Hong Kong gangster movie and which stars the young and skinny Sam Lee in his first role; and The Longest Nite, one of Johnny To’s nastiest crime dramas, with impeccable performances by Lau Ching-Wan and Tony Leung Chiu-Wai as (of course) an immoral cop and a vicious criminal.

These three classics are hard acts to follow but several of the other films on the docket manage to hold their own. Both Pang Ho-Cheung’s Love In The Buff, an excellent romantic dramedy with Miriam Yeung and Shawn Yue as the make-up-to-break-up lovers (full review here) and Ann Hui’s most recent feature, A Simple Life, starring Andy Lau and Deanie Ip as a man and his amah, (full review here) had extended runs in San Francisco earlier this year so this may be the last chance to see then on the big screen in the Bay Area.

Also good is Johnny To’s new romantic comedy Romancing In Thin Air, which To co-wrote with longtime creative partner Wai Ka-Fai and the Milkyway Image team. Set mostly at a vacation lodge in an idyllic high-altitude locale in China, the story concerns two romantically wounded individuals grappling with the peculiarities of their damaged relationships. Sammi Cheng is her usual charming self as the female lead, but although he’s likeable enough, Louis Koo as a Hong Kong movie star (!) is a bit lacking in charisma and doesn’t bring a bigger-than-life sensibility or the self-effacing humor that Andy Lau or a more engaging performer might have done.

Although the plot is seems at first to be fairly straightforward, the film gradually reveals Milkyway’s trademark weirdness. The story of Sammi’s missing husband, lost in the dense high-country woods for seven years, is a bit creepy, though I do like that when the husband courts Sammi he turns into a clumsy doofus. The film also includes a very meta movie-within-a-movie conceit and makes several sly jabs at the Hong Kong film business.

Less good are Derek Yee’s The Great Magician, a rambling and messy movie that’s a criminal waste of Lau Ching-Wan, Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, and Zhou Xun (full review here), and Roy Chow’s Nightfall, a turgid and ridiculous film that similarly wastes good performances by Simon Yam and Nick Cheung. I really wanted to like this movie, a wannabee intense and serious thriller, not least for its slick and attractive cinematography. But despite a gripping and violent opening scene the movie has some great gaping holes in logic and alternates between chatty exposition and absurd set pieces. Still, Nick Cheung is very good as a haunted convict with anger management issues, though Simon Yam is somewhat less good as the cop unraveling the mystery. Yam doesn’t have quite the emotional depth of Francis Ng or Lau Ching-Wan and so the payoff at the end of the film is weaker than it might have been. Michael Wong is quite bad as an abusive father, with a shrill, one-note performance and his annoying habit of speaking English at the most illogical moments. I kept imagining what Anthony Wong might have done with this part. The violence is a notch more gruesome than most mainstream Hong Kong films, especially in the opening fight sequence—looks like someone’s been watching Korean movies for tips on emulating their gory tendencies.

All in all, San Francisco Asian film fans are going to have to make some hard choices this weekend—not that that’s a bad thing by any means.

3rd i’s South Asian Film Festival

September 19-23, 2012, Roxie and Castro Theaters, San Francisco

September 30, 2012, Camera12, San Jose

September 21–23, 2012

New People Cinema, San Francisco

Shot By Both Sides: Chen Kaige’s Sacrifice

Sacrifice, Chen Kaige’s new movie, is now playing in San Francisco and while it’s a quality production, it seems a little dated, as well as being not quite up to the standard of past Chen flicks. But since Chen directed the epic masterpiece Farewell, My Concubine (1993), the bar for his films is pretty high. Sacrifice is certainly at least as worthwhile a watch as, say, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and most likely less insulting to your intelligence.But Sacrifice feels like a relic, caught between the old-timey expectations of international arthouse audiences and the contemporary realities of today’s Chinese film market.

My first encounter with Chen came back in the 80s when I saw Yellow Earth in New York City’s Chinatown. Chen, along with his fellow 5th generationist Zhang Yimou (who was also Yellow Earth’s cinematographer), had just busted out internationally and Yellow Earth was a huge departure from the social-realism of the Mao era. Beautiful and visually lush, with a cogent critique of China’s political and social climate, the movie was a worldwide arthouse hit and set the tone for Chinese films of the time. Chen went on to even more acclaim with Farewell, My Concubine, which famously combined Beijing Opera, 20th century Chinese history, and the divine histrionics of the immortal Leslie Cheung.

Since then Chen has directed a slew of films, though none as popular or critically beloved as FMC. Sacrifice follows in the footsteps of Chen’s most renowned flicks, but perhaps due to this it feels staid and outdated. It’s also to Chen’s disadvantage that his reputation precedes him as the director of the masterly FMC, since his films will be inevitably compared to that classic for the rest of his career.

Sacrifice is based on The Orphan of Zhao, the earliest Chinese play to be staged in Europe, and its storyline is an intricate hash of intrigue and revenge in feudal China. Set during the runup to the Warring States period, the movie follows Cheng Ying, a doctor who is caught up in court machinations. Ruthless warlord General Tu’an mercilessly slaughters his rival, General Zhao, and all 300 of Zhao’s close relatives save one, an infant son born during the chaos of the purge. Due to various byzantine plot twists, identity swaps, and other confusion, Cheng raises the surviving Zhao baby undetected in Tu’an’s court.

The first half of the movie gallops along pretty well, with court intrigue and carnage keeping things running at a brisk pace. But the film’s middle section is awfully slow and the film bogs down considerably at this point. By the end of the movie the pace picks up again, but it’s a long slog through the talky exposition in the middle section. Wang Xuiqi (who starred in Yellow Earth back in 1984) is awesome as the badass Tu’an and Ge You is also outstanding as Cheng, the doctor ground up in the court’s political gears. The secondary characters, however, are less interesting—pretty boy Huang Xiaoming (here with a decorative facial scar) is extraneous and a bit ridiculous and Fan Bing Bing adds another flower vase role to her resume. The final fight scene has some emotional heft since the characters’ relationship is well-established prior. Not so for the significant deaths earlier in the film, since those characters and their relationships are ciphers.

The costumes, art direction, and cinematography are top-notch, but throughout the film Chen makes some janky directing and editing decisions. The identity reveal of a key character is pretty botched, and Chen somewhat clumsily employs flashbacks, dissolves, and intercutting, as well as a repeated fade-to-black motif that’s more distracting than insightful.

Sacrifice is not a bad film per se but it seems a bit old-fashioned given the current state of Chinese cinema. Here in the U.S. audiences seem to think that Chinese movies are all about ponderous costumed historical allegories like Sacrifice, but in China itself the scene is pretty different, with this year’s most popular Chinese-language films to date being Wu Er-Shan’s big-budget fantasy Painted Skin 2, the WWII action comedy Guns N’ Roses, and Mission Incredible: Adventures On The Dragon’s Trail, an animated movie about a goat.

Personally, I’m much more intrigued with Caught In The Web, Chen’s latest film now playing in Asia, that looks at China’s exploding online culture, but it probably won’t see the light of day here in the U.S. for months, if at all. One of Chen’s few modern-day movies, Caught In The Web feels timely and of-the-moment and is probably way too contemporary and edgy for the staid international arthouse demographic that follows Chen. There’s nothing inherently wrong with Sacrifice, and it’s the kind of stately historical Chinese costume drama that U.S. distributors love, but its aesthetic feels as stuffy as a Merchant-Ivory melodrama in the age of Cloverfield.

UPDATE: Looks like Caught In The Web will be playing at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, which is great news. Here’s hoping it leads to more Stateside screenings—are you listening, SFIFF?

Wonderwall: 2012 San Francisco Silent Film Festival

I love a good film festival and this year’s San Francisco Silent Film Festival was one of the best. Held at the legendary Castro Theater, the festival showcased several brand new or recently restored prints of classic and obscure films from Germany, China, the U.S., Sweden, and beyond. Probably due to the popularity of The Artist, winner of last year’s Best Picture Oscar, the festival was packed morning, noon, and night.

In this age of DVDs and online streaming the SFSFF understands the need to offer a value-added film viewing experience. All of the shows at the fest had live accompaniment, ranging from glorious piano and Wurlitzer stylings to full-on ensemble performances from crack film orchestras. Wings, the opening night film, was screened not only with live music but with a live foley setup providing sound effects in the theater as the film unspooled. The screening of Georges Melies’ classic short, A Trip To The Moon (recently featured in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo), included live narration by Paul McCann from the director’s notes on the film, adding a droll note to the whimsical film.

I started my long weekend o’ film viewing with Little Toys (1933), starring the legendary Chinese performer Ruan Lingyu, who died by her own hand at the tender age of 24. Between 1927 to her death in 1934 Ruan appeared in nearly 30 films during the golden age of Chinese filmmaking, famously playing lovelorn prostitutes, and other down-and-out characters. In Little Toys she’s a toymaker in rural China who is swept up by the events of the day, including the Sino-Japanese War, the advent of capitalism, and the urbanization of China. The film, by left-leaning director Sun Yu (who ironically was later denounced by Mao Zedong), is an interesting critique of the inhumanity of war and the ways in which ordinary people are harmed by violent political conflict.

The festival also included films featuring two very different silent era actresses. Mantrap (1926), starring the awesome Clara Bow, screened with impeccable live accompaniment by Stephen Horne on piano, flute and accordion. I’d never seen Clara Bow in action before and, as directed by her then-inamorato Victor Fleming (The Wizard of Oz; Gone With The Wind) she’s fun and charismatic, with darting eyes and a sly, impish grin. The pre-code storyline of a notorious flirt who dazzles her husband and his friend, as well as most of the other men in the movie, is refreshingly non-judgmental—as Michael Sragow observes in the program notes, “the film doesn’t punish the character for her sexual independence, it salutes her for it.”

Saturday night’s centerpiece film featured another silent-screen goddess, the ever-stunning Louise Brooks starring in Pandora’s Box. The festival screened a gorgeous new restoration that confirmed director G.W. Pabst’s mastery of light and shadow, emphasizing the moody chiaroscuro that makes this film a classic. We’d meant to attend the 10pm show of The Overcoat immediately following Pandora’s Box, with music by the surprise-a-minute Alloy Orchestra, but delays in loading in the Mattie Bye Orchestra for the Pabst film pushed The Overcoat’s start time past 11pm. With plans to see the 10am show the next day we regretfully took a pass on the Russian expressionist movie and headed for home.

Sunday morning bright and early, less than ten hours after the late-night screening of The Overcoat, a full house turned out to see Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (1920), as the mild-mannered Don Diego who turns into the sexy crime-fighting Zorro. As noted by Fairbanks biographer Jeffrey Vance, Zorro’s underground hideout, his dual identity, and his form-fitting all-black outfit, cape and mask were a clear influence on Batman creator Bob Kane. In Zorro, Fairbanks of course flaunts his toned booty, fencing chops and parkour skills—more surprising are his well-honed comic chops as the foppish Don Diego. The film isn’t very cinematically innovative but once Fairbanks gets going the movie picks up steam. The climatic chase scene, with Fairbanks running, jumping and climbing his way across the scenery, is a lot of fun.

Capping the weekend’s screenings was Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman (1928), his last great feature film and his first as an MGM contract player. As a UCLA undergrad I was crazy for Buster Keaton, seeing all of his independent features and several shorts. I even watched The Navigator on a flatbed at the UCLA film archives since, back then at the dawn of time, Keaton’s movies weren’t available on home video. I’d never seen The Cameraman, though, so I was happy to that it was part of this year’s festival. Although MGM’s dictatorial studio brass was already on its way to fatally hampering his career, Keaton turned out a near-perfect movie in The Cameraman, which follows a callow young photographer in his attempts to break into the newsreel business. Along the way he woos a pretty girl, shatters many windows, leaps effortlessly onto moving vehicles, and gets caught in the middle of a full-scale tong war. Unlike many movies from the era, the film’s portrayal of Chinatown and its habitués is fairly unsensational, though I wonder if the tongs really would have had several full-on machine guns to go with their machetes and six-shooters.

All in all the festival was quite fun and invigorating. It’s always a treat when vintage movies get the royal treatment, and the SFSFF displays the utmost care and sensitivity in presenting its programs. In an age when media is often made to be watched on a cell phone, it’s great to see films produced for and projected on the all-mighty big screen.

Night and Day: More Hong Kong International Film Festival

Besides Love In The Buff and Beautiful/My Way, I also saw a few other films during my stay in Hong Kong, at both the Hong Kong International Film Festival and the Hong Kong Asian Film Financing Market (HAF). HAF is the biggest trade show in Asia for television and film distribution buying and selling, so I spent a couple days wandering the halls of the massive Hong Kong Convention Center checking out the latest product from all over Asia.

One day I caught the press conference for Painted Skin 2, where pretty male and female starlets Aloys Chen Kun and Yang Mi appeared along with director Wuershan. Wuershan’s last film, The Butcher, The Chef, and the Swordsman, followed the psychedelic journey through time and space of a fateful meat cleaver, and which earned him the chance to direct PS2, which comes out this summer. The presser was all in Mandarin so I didn’t catch any of the fluff, but the trailer looks pretty fun and the costumes and art direction promise to be as fantastical as Wuershan’s last movie. I’m afraid that I didn’t recognize Yang Mi as one of the stars of Love In The Buff, which I’d just seen the day before, in part because she’s so generic looking. I didn’t stick around for the press conference for The Bullet Vanishes, even with the lure of the possible appearance of star Lau Ching-Wan, but apparently only Jaycee Chan, Yang Mi, and a couple other starlets were in attendance so I don’t think I missed much. On my way out I came across a random TVB press conference with yet more starlets, this time in period dress, promoting an indeterminate historical drama.

HAF and HKIFF both screened a slew of movies that have yet to see release in the U.S., so I tried to catch as many of those as I could. Himizu, Sion Sono’s new movie, is a hot mess, yet at times it’s also visionary in its extreme and unflinching critique of the human condition. The film uses post-tsunami Fukashima as a metaphor for the decline of humanity, as seen through the eyes of hapless teen Sumida and his admirer, fellow child-abuse survivor Chazawa. Sumida is the forlorn son of an abusive gambler and a neglectful mother who run a crappy boathouse on the outskirts of town. Enduring several beatdowns from his useless dad, the loan sharks chasing him, and various random gangsters, Sumida eventually takes matters into his own hands, with the help of Chazawa, the rich girl crushing on him who’s also got some weird family issues. Though overly long and in desperate need of a more disciplined narrative structure, the film is nonetheless engaging and in several scenes quite gripping. Shota Sometani and Fumi Nikaidou are very good as the oppressed teens, with Sometani in particular bringing a fierce intensity to his role as the beaten-down yet not defeated protagonist who struggles to find a moral center.

The Second Woman, Carol Lai’s thriller, stars Shawn Yue and Shu Qi as Nan and Bao, two lovers who perform together in Chinese theater troupe. Their relationship is complicated by the presence of Bao’s identical twin Hui Xiang, who is also a wannabe actress. When Hui Xiang secretly subs for Bao during a performance the hijinks ensue. The Second Woman clearly aims to replicate the backstage psychological drama of The Black Swan in its use of the theatrical milieu and its Freudian (or is it Jungian?) identity confusion. It’s a handsome and expensive-looking production but all too often relies on really loud and sharp blasts of music, dark objects suddenly falling from offscreen, and other hoary cinematic devices to provoke the viewer’s jumpiness factor, rather than truly creepy or frightening events. It doesn’t help that Shu Qi’s twin characters don’t have a lot of distinguishing features, with the exact same hairstyle, wardrobe, and facial expressions. As the fulcrum of the love triangle Shawn Yue doesn’t have much of the charm that he exhibited in Pang Ho-Cheung’s Love In A Puff/The Buff. The movie is a tepid attempt at psychodrama that the lacks narrative tension or engaging characters that would give the film some force.

I had high hopes for The Great Magician, since it was directed by Hong Kong stalwart Derek Yee (Lost In Time; C’est La Vie, Mon Cherie: One Nite In Mongkok) and stars the A-list cast of Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Lau Ching-Wan, and Zhou Xun. The film is set in the 1920s during the Republican Era in China and has high-tone production values and art design by Oscar-nominated Chung Man-yee. It’s a glossy picture with all kinds of talent and an interesting premise, but in the end it falls flat, suffering from an inability to maintain a consistent filmic tone (is is a comedy? a romance? a satire? an action movie?).

The movie also feels about thirty minutes too long, and here again I must lament the decline of the 90-minute Hong Kong action movie. When Hong Kong directors worked within an hour and a half running time they finely tuned their narrative structures to cram the story and action into that rapid-fire time length. Now that Chinese-language films have begun to creep toward the 2-hour mark it seems like many Hong Kong productions start to tread water around the 45-minute mark in order to fill up the screen time, to the detriment of pacing and action and without compensating by more advanced character development. Such is the unfortunate case in The Great Magician–if the movie had been tightened up by 25% the flaws in its execution might have been reduced by the sheer energy of its breakneck pace (which has many times been the case in even the most celebrated Hong Kong films). Here the unforgiving two-hour run time stretches the unfocused storyline and the movie’s mugging and sight gags start to repeat themselves, ending up in a flaccid, badly paced, expensive looking spectacle. There’s no excuse for an action comedy starring Little Tony, Lau Ching-Wan, and Zhou Xun putting me to sleep, which this film did, which is a criminal waste of underused talent.

If I’d been able to I could have easily seen many more films than these at HAF and the film festival, but since my visit was limited to a week I felt like I should spend some time outside in the sunshine instead of lingering in darkened rooms all day. Clearly I underestimated by not booking many more days (or weeks!) in Hong Kong, but alas, my responsibilities in the U.S. called me back home. Here’s hoping for another, longer trip some time in the near future.

Don’t Stop Believin’: An Interview with Filmmaker Ramona Diaz

Don’t Stop Believin’: Everyman’s Journey, Ramona Diaz’s new documentary about classic-rock band Journey’s Filipino-born lead singer Arnel Pineda, premiered last month at the Tribeca Film Festival and showed here as the closing night film at the San Francisco International Film Festival. After attending the closing-night show, which also included Arnel and his bandmates live in person, I had the chance to chat with Ramona (who also directed the excellent documentary Imelda, about the former first lady of the Philippines), where she discussed the camera as confessor, converted haters, and the difficulty in finding late-night noodles in San Francisco.

BeyondAsiaphilia: I saw the movie on a DVD screener and then watched it again at the Castro last night, which is a really different experience. The film really works with the crowd. I loved how everyone cheered at the end as if they were at the concert.

Ramona Diaz: Yes, that happened at Tribeca, too. Even with jaded New Yorkers. The crowds have been incredible. It’s nice because you never know how a movie is going to be received.

BA: In Imelda you do a great job making Imelda Marcos a really fleshed-out person, for better or worse. How did she react to the film once she saw it?

RD: She tried to get a restraining order in the Philippines–she sued us in the Philippines but we won, so she let it go. When she saw the New York Times review she how people saw her. It was scary because you don’t want to have to pay all that money but we won. Luckily we got a lot of pro bono work from human rights lawyers who helped us out.

BA: So it’s interesting that you also have Arnel Pineda as an icon, but you personalize him in the same way.

RD: Well, you try to personalize someone and make them flesh and blood, or what’s the point? But when I met him I knew that he was golden. He’s a great narrator of his personal life in whatever language, although he’s more comfortable in Tagalog. The film is a happy story but inside that story is an angst-ridden artist trapped in a fairy tale. He addresses that in the language. Filipino audiences get it—it’s not even a word, it doesn’t translate—he’s kind of sarcastic about it. He knows that things don’t last. It’s a function of his personal experience and what he did to survive on the streets. He can talk about it in a real and fresh way.

BA: Where did you first meet him?

RD: I met him to the when Journey was rehearsing for the tour. I went to shoot a trailer to prove to the band that they had a story. The camera loves him and he returns the love to camera. I’m glad we made the movie in his first year because it would’ve been a very different film in the second year with the band. Now he has a personal assistant—in the first year the camera was his confessor.

BA: Was the fact that you’re Filipino helpful in the process of making the film?

RD: Yes, I was the only other Asian face in the whole band (entourage) and it really helped that he could talk to me. My crew was also very low-key and he got to trust them. Jim Choi was fantastic—he did sound and camera.

BA: You talk about how the band adopted this nation. I like how the Filipino fans are featured in the movie in an interesting way. They’re really present in the film.

RD: They just became more and more present as the tour progressed.

BA: So they found about him gradually?

RD: Oh, yes. With Filipinos word gets around!

BA: So where did you shoot that scene where all of the Filipinos are there with the t-shirts and signs and everything?

RD: That’s at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles.

BA: That’s just a wonderful moment in the movie because he seems so surprised.

RD: Yes, Arnel was just looking for a signal and he was totally surprised at all of the people there to see him. And yet he stood there and signed everything for a good half hour. He might not do that nowadays—now he has a roadie to protect him.

BA: Does he do that now, now that he’s more used to it?

RD: Not so much any more. It’s not a good idea to prolong those things. He has to save his energy for the stage and performing.

BA: Why has he become this icon to Filipinos?

RD: He represents someone breaking through the mainstream, and he’s a talented and wonderful person. He’s very kind to his fans and they’re kind to him. We had to cut this out of the movie but they give him a lot of gifts—clothes, clothes for his wife, clothes for his son.

BA: A friend of mine said that Arnel is kind of an Overseas Foreign Worker. He’s doing this diasporic thing where he has to leave his home in order to make a living. It must be comforting for him to see these Filipino Americans treat him like a family member and make him feel a little bit more at home when he’s away from his home.

RD: He is in a way the ultimate OFW but in a way not—he’s in a different league. He flies back and forth to the Philippines first class.

BA: So he really makes a point of going back to the Philippines?

RD: He refuses to live in the West and now his family tours with him—after the first year he wasn’t alone.

BA: So when you started to make this film did you expect him to become so popular?

RD: Well, it is Journey—someone at Tribeca asked me, “Is Journey really popular?” They’ve got 21,000 people at their shows every night for 90 shows. Converted fans love him. I knew he’d be popular in the Filipino American community.

BA: But some of the response has been, “Where did this person come from?” For people who aren’t Asian American the Philippines could be the moon for all they know. And of course he’s very talented and good at what he does and that helps a lot. But he does mention really briefly in the movie about the haters, the people who didn’t like him in the beginning—there’s one woman who says, “I wish he was American.”

RD: That’s petered out—what are you gonna do? You can’t force people to like you—there’s always racism, so you just have to deal with it and move on. So he really blocked it out. It’s easy to do because you’re in the Journey bubble. What do you care if the bloggers hate you? There will always be hardcore Steve Perry fans who never accept you.

BA: What if Arnel had lost his voice like Steve Augeri (Journey’s previous lead singer)? Did you ever have that thought?

RD: You never know what will happen at the beginning of the shoot–if he’d lost his voice and had to drop out it’s a darker film. You don’t participate—you just go along with it.

People ask if there were creative differences but there weren’t very many. He was their ticket to a very popular summer and everyone had a great time.

I think they were also happy because they took a leap of faith to hire this guy from what seemed like across the universe—who knew if he would work out? It was a leap of faith that worked, so everyone was very happy about that.

BA: How has it been screening the movie?

RD: It’s very exciting and fun. I love the shooting and the process but it is a lot of work. I’m so glad that people are responding so positively. One person said to me, “It seems like a real film!” Meaning maybe not a documentary! I think people have to be educated about documentaries.

BA: You guys were on the road shooting for four months?

RD: We were on the road for four months, plus we went to the Philippines three times. It’s been fours years this month since we started working on the film. My last film, The Learning, was in post when we were about to start this one so I was hesitant at first, but you have to take the opportunity when it comes.

BA: You mentioned funding last night—what support did you get for the film?

RD: We put it on our credit cards and we were working our ass off on commercial jobs to pay for our next shoot. We didn’t get money from the traditional sources like ITVS, since there wasn’t time (to apply). It’s also not a fundable film in the usual sense. Some funders said “It’s too commercial for us.” A lot of people working on the movie deferred their payment—it’s a fun gig, so they were happy to do it. When you’re used to shooting wars in Afghanistan this is much more fun, even if you’re driving around in a mini-van all day. At least at the end of the day you get to stay in a nice hotel.

BA: So this is much more relaxing! Well, congratulations again, this is a really fun movie. We all know how the story ends, that he’s successful, so for me as a filmmaker to watch how you structure that story is also very fun. It could’ve been very maudlin or sentimental and it’s not, it always has a very interesting edge to it.

RD: Arnel takes you out of that sentimental world—he’s a realist. He and his wife have both been around the block a few times so they have a good perspective. He went from nothing to everything in the space of a few months.

BA: So do you still keep in touch with Arnel?

RD: I just saw him off the to airport—I still see him quite a bit. We went to have noodles in Chinatown late last night. San Francisco is such an early town! It was hard to find a place that was open but luckily there was something in Chinatown.

Bonus beats: Arnel Pineda sings “Why Can’t This Night Go On Forever” acapella at the SFIFF Closing Night Q & A for Don’t Stop Believin’: Everyman’s Journey. Thanks to APEX Express for the clip!

Hit ‘Em Up: Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale film review

Opening this weekend in the U.S., Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale has bloody battles, fierce beheadings, brave sacrifice, facial tattoos, evil Japanese, and everything else you could ask for in an action movie. It’s another example of the huge growth of the commercial Taiwanese film industry which, as I’ve noted before, is a long way from the arthouse days of Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-Hsien.

Seediq Bale (which translates as “true man” or “real person”) is the most expensive Taiwanese production ever, and it’s also one of last year’s most popular films in Taiwan and Hong Kong (it just came out in China this week). It was originally released in a four-and-a-half-hour, two-part version in Asia—here in the U.S. we get the trimmed-down festival edit that only runs 2.5 hours. The shorter version seems to hit most of the significant plot points and moves along at a brisk pace, especially once the fighting starts.

Interestingly enough, the film is directed by Wei Te-shing, who also directed the sentimental and cheesy rom-com Cape No. 7, which featured a curiously nostalgic view of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan. In Seediq Bale Wei corrects Cape No. 7’s soft-focus representation of the occupation, as the Japanese are portrayed as fascistic aggressors who deserve to become machete-fodder for the vengeful Seediq.

Seediq Bale is based on the Wushe Incident, a real-life event during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan when in 1930 some few hundreds of indigenous Seediq tribespeople rose up against the colonizers. The fighting lasted almost two months, during which the Seediq, despite the Japanese troops’ superior numbers and firepower, killed more than one thousand Japanese soldiers and undermined the Japanese operations in the Wushe region.

The film starts out with the Seediq blissfully hunting boar, chanting and dancing, and squabbling amongst themselves about who has the most swag. Their little jungle paradise, however, is soon disrupted by the arrival of the conquering Japanese, who won the island of Taiwan from the Chinese in the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki. Not unlike the fate of the Native Americans after the arrival of the Europeans, the Seediq are subjugated by the maurading Japanese, with their hunting curtailed and their jungle homelands cut down. After a couple decades of the Japanese usurption of their culture and territory, Seediq chief Mouna Rudo decides to take matters into his own hands and plans with his clan to kill the Japanese squatting his land and to retake control of the jungles.

Director Wei makes great use of the gorgeous terrain, with his gliding camerawork following the fleet-footed Seediq racing barefoot through Taiwan’s jungles. He also contrasts the bland and unimaginative, uniformed Japanese with the wild and wooly, improvisational Seediq, who used their familiarity with the landscape to corner and ambush their befuddled foes. Clearly espousing the tenets of guerilla warfare, one Seediq says, “You have to think like the wind–it’s invisible.”

There’s no denying the sheer pleasure in watching a persecuted minority rise up to utterly decimate its oppressors, and to see the Seediq outwit the Japanese and literally cut them down to size is an unholy joy. Yet the film avoids becoming a good native/bad invader polemic by also showing the intratribal strife among the Seediq—not all of the tribal chiefs wholeheartedly supported Mouna Rodu’s quixotic rebellion and some of them actively oppose it, taking revenge for old slights by siding with the Japanese against Mouna’s clan.

The film is both a liberation story and cautionary tale, demonstrating both the need to fight back against the oppressor as well as the great cost of the struggle for sovereignty. A long and emotionally intense passage shows a group of Seediq women, who are as dangerous as the men, sacrificing themselves for their tribe by committing mass suicide. There’s also an interesting subplot about the cultural conflicts of two of the Seediq who have assimilated as low-ranking policemen in the Japanese occupying forces.

Movie idol Masanobu Ando is fierce and gorgeous as per usual as a Japanese soldier who befriends some of the Seediq, but the film’s real star is first-time actor Lin Ching Tai as the scary-good Mouna Rudo. Lin is charismatic and convincing as the badass leader of the Mehebu tribe who decides to stand up to the abusive Japanese invaders, rallying his troops with declamations about the blood sacrifice that will enable them to earn the facial tats they’ll need to enter the afterlife’s fertile hunting grounds.

Also aces is the adolescent Lin Yuan-Jie as Pawan, a young Seediq warrior in the making who earns his tribal tattoos by wielding a mean machine gun. Other Seediq parts are filled by various Taiwanese pop stars with real-life aboriginal blood, including Vivian Hsu, Landy Wen, and Umin Boya. The inclusion of these celebrities is a shrewd move on the part of Wei, as it increases box office appeal while at the same time pointing out the previously overlooked indigenous heritage of some of Taiwan’s most popular singers and actors.

The film’s message is that it’s better to die a brave death as a free man than to capitulate to the colonizer, even against impossible odds. Passionate, violent, and entertaining as hell, the movie is a glorious tribute to its downtrodden protagonists who fight back against colonization and extermination in order to preserve their cultural beliefs.

NOTE: Apparently the success of Seediq Bale in Taiwan (it won Best Picture at this year’s Golden Horse Awards) has spurred an upsurge of interest in indigenous Taiwanese culture, including the building of Seediq Bale Park in Taipei that recreates one of the film’s locations. There tourists can see props from the movie and purchase memorabilia, although, unlike in the movie, the streets are probably not strewn with headless corpses.

Recent Comments