Posts tagged ‘movies’

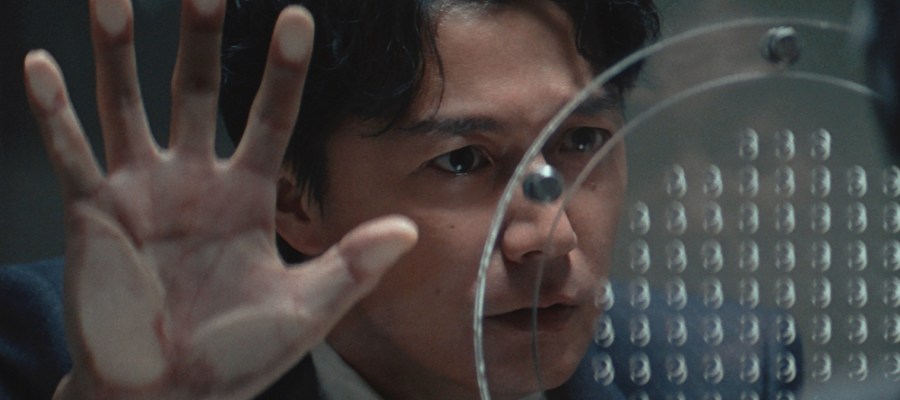

Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood: Carol Doda Topless At The Condor film review

San Francisco’s North Beach is right next to Chinatown, so growing up in the Bay Area I vividly remember seeing the giant neon sign at the Condor Club at Columbus and Broadway every time my family made the trek to the city for a wedding banquet or a red egg party. I always wondered who the woman in the billboard was and why she had bright red lightbulbs on her bra but of course it was not to be discussed with my parents or any other adults who happened to be driving the car. Once I got older I learned who Carol Doda was in a general sort of way but I didn’t know too many details about her life or how she came to have her likeness in lights at a club in North Beach, so I was happy to learn more via the new documentary, CAROL DODA TOPLESS AT THE CONDOR (dir. Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker), which takes its name from that very neon sign that mystified me as a kid. Doda started her career as a go-go dancer and cocktail waitress there back in the early 1960s and when she became the first performer to go topless in 1964 she became a sensation.

The film does a good job evoking the time and place when San Francisco was the hippest place around. In the early 60s the beatniks were fading away and the hippies had not yet taken over, but San Francisco was still the place to go for vacationing Midwesterners looking for edgy entertainment. Doda was at the center of the scene and people lined up around the block to see her dance and sing in her g-string. The film tells her story through interviews with Doda’s contemporaries as well as from archival interviews with Doda herself (she died in 2015) and features copious amounts of archival footage from back in the day.

For the most part, like most biographical documentaries the film emphasizes the positive. It hints at a bit of the darker side of Doda’s story including her unhappy marriage at a young age and her estrangement from her children from that marriage and there is one scary shot of the very large needle used for silicone breast enhancement (Doda went from a 34B cup to a 44DD using silicone). There’s also a harrowing tale of a fellow dancer who developed gangrene in her breasts because the silicone blocked her milk ducts when she tried to nurse her infant, but the film isn’t an expose of the wrongdoings of the boob job industry. Instead it focuses on the perspective of Doda and the other dancers interviewed who describe the financial and personal freedom that topless (and later bottomless/nude) dancing afforded them. The movie frames Doda as a proto-feminist who actively chose her profession and places her in the context of the sexual revolution, the Summer of Love, and the women’s liberation movement, arguing for the agency and self-determination of Doda and her fellow dancers.

The film also traces the rise and fall of North Beach, which by the 1980s had become a much seedier place, as illustrated by the questionable death of Jimmy “The Beard” Ferrozzo, one of the managers at the Condor. Ferrozzo had some unfortunate encounters with organized crime and in 1983 he was crushed to death after hours one night by the hydraulic piano that Doda danced on top of in her show. The film also points out that in the 60s, couples and businessmen made up a big part of the audience at Doda’s shows, but by the 80s it was primarily single dudes, probably in raincoats.

All in all the film is a fascinating, wide-ranging and entertaining look at the era, with Carol Doda literally emboding that era. It’s a fun watch and it satisfied my curiosity about that giant neon sign and the woman that it represented.

The Beautiful Ones: Wong Kar-Wai retrospective at BAM/PFA

A cinematic treat dropped at the end of 2020 as the Lincoln Center in New York launched World of Wong Kar Wai, its retrospective of mostly 4K restorations of Hong Kong New Wave auteur Wong Kar Wai. The bulk of the series has traveled to various venues including the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, where nine films are currently available for online viewing through February 28, 2021. The Roxie Theater in San Francisco is also showing seven films from the series through Feb. 25, 2021, including a screening of In The Mood For Love on Valentine’s Day at the Fort Mason Flix drive-in. Although it’s great that the films are available to view in all of their restored 4K glory, it’s bittersweet that audiences aren’t able to watch them on the big screen where they belong due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis in the US.

I watched the BAM/PFA series in chronological order, and it was interesting to see the development of Wong’s signature style. His debut feature, As Tears Go By (1988), is a gangster film that stars Andy Lau Tak-Wah as Wah, a low-level triad in Mongkok who is constantly vexed by his triad brother Fly (Jacky Cheung), whose struggle with toxic masculinity conventions leads to much rash and insecure behavior.

Although the film loosely follows the trajectory of classic gangland films such as Mean Streets, in which the poor life decisions of one character leads to the downfall of his sworn brother, Wong’s filmmaking style had already begun to establish itself. The audacity of some of the shots, such as the focus on the sharpness of Andy Lau’s jawline or the beauty of a cigarette burning blue in the dark, heralds Wong’s trademark visual characteristics, as does his use of slow motion action, neon lights and silhouettes. The film also includes the breathtaking sexiness of Maggie Cheung and Andy Lau in their underwear wrestling on a bed in a hotel room, another element of Wong’s emerging style as he begins to sketch out his aesthetic.

Wong’s stylistic elements came into sharper focus with his second feature, Days of Being Wild (1990). It’s a bit overwhelming to have a film populated with so many gorgeous movie stars at their physical peak, led by the sheer charisma and stunning beauty of Leslie Cheung in his prime and it really should be illegal to be that good-looking. Carina Lau holds her own as the feisty bar girl who gets involved with him. Maggie Cheung is mostly mopey and jilted in this one, though by the end of the movie she’s found her peace. Andy Lau is once again shockingly good-looking and photogenic–never has such a bone structure been so lovingly photographed. Jacky Cheung again plays the sad sack best friend, but here he’s much more restrained and nuanced. The movie closes with the famous mystery scene with Tony Leung Chiu-Wai in a very small hotel room preparing to go somewhere where he’ll need two packs of cigarettes and a deck of cards.

Chungking Express (1994) is still as fresh and exciting as the first time that I saw it more than 25 years ago. Light and airy, quirky and charming, with pitch-perfect performances, it captures Hong Kong’s day-to-day life without malice or darkness. Wong’s film explores the transience of life and the fleeting relationships in a big city where anything can happen and the world is open and free. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle establishes the iconic Wong Kar-Wai look with his lighting design alternating between the moody, neon-lit style of the first story and the bright, natural lighting of the second story. Once again Wong’s cast of topline movie stars, including Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Brigette Lin Ching-Hsia, Faye Wong, and a 20-year-old Takeshi Kaneshiro, adds glamor and razzle-dazzle to the film.

Fallen Angels (1995) is a much messier and less compact film than Chungking Express, full of neon lights, dutch angles, and rain-slicked streets. If Chungking Express was Wong’s renaissance masterpiece then Fallen Angels is his baroque turn, where all of his directorial tics are turned up to eleven. Karen Mok is in it too briefly and Leon Lai too much, but as in Chungking Express Takeshi Kaneshiro is quirkily incandescent. His character’s story is good enough to stand alone, with able support from a wacky Charlie Yeung and Chan Man-lei as his stalwart dad.

Although as full of visual bravado as Fallen Angels, Happy Together (1997) is a stronger film because its character development is more complex. Tony Leung Chiu-Wai is at his angsty best, conveying a kaleidoscope of emotions with a few flashes of his eyes, while Leslie Cheung is devastatingly effective as his mercurial lover. A gorgeous, moody film full of humanity, compassion, and sadness, this is Wong at his poetic best.

Trippy and elliptical, Ashes of Time Redux (1994/2008) holds up better than I recall from my initial viewing when the film was first released. All of the beautiful people are in this one (except for Andy Lau), including Jacky, Brigette, Charlie, Maggie, Carina, both big and little Tony, and Leslie as the lead character and narrator. Side note: why didn’t Heavenly King number four (Aaron Kwok) ever make an appearance in a Wong Kar-Wai movie? Too short and stocky? These things keep me up at night.

The odd narrative works if you let go of any expectation of linearity and it’s now quite amusing to see so many A-listers with their million-dollar faces obscured by matted hair, but there you go. Although when the film was first released martial arts purists were horrified by the blurry camerawork that wasted Sammo Hung’s action choreography, now it seems to all fit together with the tangled hair and blowing sands and Christopher Doyle’s grainy, oddly saturated cinematography.

In The Mood For Love (2000) is perhaps Wong’s most acclaimed film, and justly so. All elements of the movie, from mise en scene to acting to cinematography to direction and editing, are stellar, led by Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung’s performances as star-crossed lovers. As with all of the 4K restorations in the series the digital remaster is sharp and beautiful, with the film’s saturated jewel tones shining through.

2046 (2004) is an example of what happens when a filmmaker is given an unlimited budget and full artistic freedom as the movie is obtuse, too long by at least thirty minutes, and could jettison its entire science fiction framing device. However, the main part of the film, set in the late 1960s and a loose sequel to In The Mood For Love, is great, with Tony Leung now a womanizing cad following his failed relationship in the earlier film. Zhang Ziyi as his call girl lover is dynamic and magnetic, matching Tony’s acting chops beat for beat . Along the way Gong Li, Carina Lau, and Faye Wong make appearances, though their characters don’t have much arc to speak of.

The BAM/PFA and the Roxie series both include the little-seen one-hour film The Hand (2004), which was a revelation to me as it was the only film in the program that I hadn’t yet seen. Originally released as part of the three-part omnibus Eros (along with segments by Michelangelo Antonioni and and Stephen Soderbergh), The Hand is a gorgeous meditation on class and gender divisions and unrequited love, and Wong goes all in with his cheongsam fetish. Gong Li as a courtesan falling on hard times and Chang Chen as her longtime admirer are amazing and the opening scene that the film takes its name from is a stunningly kinky set piece. The film makes a strong argument that Wong Kar-Wai should only make films set in the 1960s as the evocative art direction, from hair to costumes to set design, is on point and breathtaking.

Although this series emphasizes his auteurship, Wong Kar-Wai didn’t operate in a vacuum. His work was nurtured by the strongest film industry in Asia at the time, one that churned out hundreds of movies every year that were exported all over the region. In some way Wong’s films gave an entre into Hong Kong cinema to snobby cineastes who might have disdained genre directors like John Woo or Tsui Hark. This retrospective brings back memories of that brief shining moment when Hong Kong was the center of the cinematic world. It’s especially melancholy to consider through the lens of 2020/21, when the city has been so drastically changed by China’s brutal repression of free speech there.

Existence Is Longing: Wong Kar Wai

Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive

December 11, 2020–February 28, 2021

Roxie Virtual Cinema

Available until February 25

Roxie Cinema

San Francisco

Drive-in screening of In The Mood For Love

Sunday, Feb. 14, 7pm

Fort Mason Flix

Queen of Hearts: An interview with Yellow Rose producer Cecilia R. Mejia

Yellow Rose (dir. Diane Paragas) is currently in the midst of its theatrical run in the US after taking the Asian American film festival circuit by storm in 2019. I talked with producer Cecilia R. Mejia about the film’s significance to herself and to the Asian American community at large.

BA: So it’s pretty exciting, to get theatrical distribution.

CM: When we got bought by Sony, it was exciting. And then with COVID, we didn’t know what was going to happen, but Sony said, we’re gonna do it anyway. So it’s been like a little weird, because we don’t know what the box-office numbers would have been if people felt safer to go to cinemas. But conversely, we also don’t know if they would have put us in that many theaters if COVID wasn’t happening.

BA: It’s funny because I had a film (Love Boat: Taiwan) that was playing at a lot of the same festivals as Yellow Rose, and it was always sold out before I could get a ticket. And it always won all the awards. I remember saying, “Yellow Rose is playing with my movie again–oh, well, there goes all the awards!” (laughs)

I teach Asian American film history, so that’s another reason I was super excited about this movie, because it’s a Fil-Am film, And the last Filipino American movie that I remember being in theaters might have been The Debut back in like 2000.

CM: I think they they also did it themselves–they self-distributed.

BA: That’s right, so it’s different because you got a major distribution deal. Are you the first Filipino American film to do that? Probably HP Mendoza did more like an indie route. He definitely wasn’t with Sony.

CM: I think it’s safe to say that we’re the first by major studio, so it’s super exciting to have that backing.

BA: What do you think contributed to you being able to get that kind of deal?

CM: I think some of it was the music. What makes our our film quite different is there’s the added element of the music and Sony also does music, so they also have the soundtrack that they’re pushing. I think what was appealing to them was, here’s this really interesting story about a community that’s never really seen on screen, and there is this element of country music, which is very popular.

BA: And Lea Salonga is in it too, right?

CM: Yes, she’s probably the most well-known Filipina in the world, along with Manny Pacquiao. She has a huge following. I think people really fall for Eva (Noblezada) too. People say to me, I feel like we’ve found a star.

BA: I’ve only heard good things about the movie. I mean, a film can be popular, but there’s always someone who’s hating on it. And I’ve never heard any hate for this movie.

CM: I know! We had a great festival run. We couldn’t have asked for a better opening than at Los Angeles Asian Pacific American Film Festival.

BA: How do you feel about like this giant Asian American film festival circuit? And how did that help out with getting more visibility for the movie?

CM: I think it helped a lot. I actually studied Asian American Studies in school, but I hadn’t really collaborated that much with other groups outside of Filipino Americans. And I thought, “I need to do that.” I feel like if we had been in those big festivals (like Tribeca), the film might not have been embraced the way that it was or understood the way that it was. It was just embraced by every community that we showed it in. And I just feel like it was nice to introduce some of our people and our crew members to the world of Asian film festivals because they hadn’t been part of any of that.

So I think I think it helped us because it gave us this boost and it helped build this community. I think the traction that we were getting at every festival was getting some buzz–people were talking about our film. Every time we were we were somewhere there was so much buzz.

BA: Yes, I think it was the buzziest movie last year at Asian American film festivals.

CM: Yes, and around this time of the year the festivals seem to all be around the same time. We had to divide and conquer–Diane was in Hawaii and San Diego. And I went to Philadelphia, Vancouver, Houston. It was like this whole circuit. And it was interesting, because we were all texting each other, “I think we won!”

BA: When you made the movie, I can’t imagine that you thought that it would be so popular. Do you remember what you were thinking when you started working on the film? Why did you decide you wanted to do this story?

CM: The backstory was that I have been working on this for almost a decade with Diane (Paredes), the director and writer. She herself has been working on this for more than 15 years and she had just sort of given up at some point and started her career as a commercial director, did a documentary. And then she decided, “I want to tell the story.” I was working with the Philippine American Legal Defense Fund at the time, was just out of grad school and I wanted to embed myself more in the public policy world. I was also working in and out of the UN, signing up people for DACA and working with Jose Antonio Vargas. And Diane came to our office to do research. She said, “I’m doing a film on an undocumented Filipino immigrant who loves country music,” and she showed me the look book. And I was so intrigued by it, because I’ve always been a lover of films, especially indie film. I didn’t think it was possible for me to infiltrate or be part of that world. So when she was showing it to me, I was really fascinated–I had never met a Filipino filmmaker before. So she asked me, “Do you want to do help me do research on it?”

So I was helping her and it snowballed. I was working on a really short documentary about undocumented Filipino immigrants who were detained, which we used as research. And then we were writing grants, and I was helping her reach out to the Filipino community and reaching out to different people. As the years were rolling on I started working as a full-time producer with her.

You mentioned The Debut–I had never seen a film that represented us since The Debut. I was waiting for something like that and so that was one of the driving forces for me–the whole backstory of a girl trying to find a home and understanding that experience from that perspective. So my goal was always to get the movie made, that was always kind of in my brain.

BA: Is there anything else that you personally really have gotten out of this experience? How has it changed your life?

CM: If I hadn’t worked on this film think I probably would be in some sort of government position, or heading towards public policy. But I’ve come to realize, especially in the last three years working with PJ (Raval) that there’s this medium of art and activism that is quite powerful. And if you watch someone like PJ navigate what he’s doing with his documentary Call Her Ganda, you see the impact of it. So this whole experience has helped me define where it is I want to go. It’s melded the things that I love most, as far as work is concerned–art, education, and philanthropy.

I think for most people film is a medium that reaches almost everyone. Whereas in public policy, you have to play politics more, and it’s also such a huge system. And you have to be like an ambassador or someone who works closely with an ambassador to get anything really done, otherwise, you’re just sort of kind of moving the machine and absorbing information. Whereas I think with film you’re able to do stuff quicker.

BA: Even though it takes like five years to finish a movie. (laughs)

CM: It’s not just this whole traditional medium of film, but art in general, I think, that has a way of changing culture in a way that nothing else can.

My goal is for people to leave the theater after watching this film and changing the way they think about immigration and about how they experience the Filipino community.

BA: Is there anything else you want to add before we finish?

CM: Yeah, there’s this. There was a review we’d read early on that was clearly written by a white woman. And she said that Yellow Rose was a white savior type of movie, because we have a lot of white characters. And I thought that was such an unfair comment, because I don’t think she did the research about who was behind the film. I also thought it was a dangerous review, because it also deters people from wanting to see the film, and supporting a community like ours, supporting filmmakers like Diane. So I thought, you know, how dangerous and irresponsible for a reviewer to do that. I don’t think people know the Filipino community, which is why maybe she said that, because she has no familiarity with it. So maybe since this month is Filipino American History Month, people maybe need educate themselves on who the Filipino American community is.

We had generally great reviews for the most part, but when I read that review, I thought, maybe because she saw Sony was behind it, maybe she didn’t know the backstory of how long it took for this movie and that it was actually the Filipino community that that funded this film. Or how historic it is to put Eva Noblezada and Lea Salonga in one film together, and someone like Princess Punzalan who’s an icon to the Filipino community, and the fact that Diane is the director and writer, and that this was a Filipino American-led film.

I think that that’s that’s something that mainstream viewers can’t understand, why it’s so important that these movies are there for us. It means more than just paying money for a ticket and watching something. We have our hearts and souls invested in these films.

BA: I just I just feel like every Asian American film that gets finished is like a miracle, honestly.

CM: Yeah, And I hate that some people say, well, we already had The Farewell. So literally, there’s that (Asian American film) for this decade. We’re two totally different stories!

Yellow Rose is currently showing at theaters across the US.

New Power Generation: Jia Zhangke and Lunar New Year films 2019

Jiang hu, Ash Is Purest White, 2018

This has been an interesting few weeks in Chinese-language cinema screenings here in the Bay. This is due in part to the recent Lunar New Year/Spring Festival holiday in China and related territories, during which a whole slew of new movies were released to capitalize on the extended vacays of most people during that time. Because of the glut in product and the large Chinese-speaking population in the Bay Area, a select few of those releases made it across the Pacific to San Francisco movie houses. Coupled with an extended series of films by one of China’s premier arthouse directors, this meant that I managed to catch many Sinophone films in the month of February.

Cameos, Missbehavior, 2019

I started my Lunar New Year viewings with Pang Ho-Cheung’s Missbehavior, one of two Hong Kong films that made it to San Francisco in February. (Sadly, I missed the other one, Felix Chong’s action thriller Integrity, due to scheduling conflicts). Pang is Hong Kong’s 21st century bad-boy auteur who’s racked up a number of well-received hits including Isabella, Vulgaria, Aberdeen, and his Love In A Puff series that stars Miriam Cheung and Shawn Yue. Miss Behavior is a low-budget quickie that carries on in the best tradition of New Year’s films, with a big cast with many famous people making cameos, a lighthearted comic tone, and a lowbrow sensibility including an extended sequence of the glamorous Dada Chen discussing her bowel movements. Though it’s not one of Pang’s deepest or most thoughtful films (the setup involves a group of friends frantically trying to locate a bottle of breast milk) the narrative is actually very well-constructed and it moves along at a good clip, briskly shuffling its many characters in and out and climaxing with a free-for-all in a big ol’ shopping mall after hours.

Spectacular, The Wandering Earth, 2019

On the other end of the production-values spectrum is China’s very first foray into the big-budget science fiction genre, The Wandering Earth (Frant Gwo). Based on a short story by well-known Chinese author Liu Cixin, the movie is a big, spectacular piece of moviemaking that rivals anything that Hollywood has put out lately. Although there are no aliens, the film does include huge vistas of spinning planets, individuals at peril in space and planetside, spaceships and other hardware exploding, random science-babble, and other markers of every sci-fi movie of recent vintage. The production design is also on point, portraying an Earth of the near future as dark, chaotic, and polluted (not unlike modern-day Beijing).

Collectivism, The Wandering Earth, 2019

But at heart it’s a Chinese production, emphasizing collectivism over individuality and the importance of very long-range goals. Also of note is the absence of almost any US presence to speak of—in China’s futuristic vision everyone speaks Mandarin, Russian, French or Japanese, and most of the planetside action takes place in China or other Asian countries. A massive box office hit in China, the film grossed more than US$300 million in its first weekend of release and has gone on to an impressive haul of more than US$650 million worldwide in just under four weeks.

And on a different tip entirely was the Jia Zhangke series at SFMOMA and BAM/PFA that included Jia himself in person at two of the screenings (a delayed plane flight prevented him making a scheduled third appearance at a show earlier in the series). The series included every one of Jia’s feature films (documentaries and narratives both), as well as films by other directors that have had some direct influence on his work.

Underbelly, Unknown Pleasures, 2002

Some of the pairings worked really well together such as the double-bill including Jia’s Unknown Pleasures (2002) and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Boys From Fengkuei (1983), both of which looked at aimless young people wandering through life. Jia’s film explores the seamy side of China, with Jia using the under-construction highway between Datong & Beijing as a visual metaphor for the rough underbelly of China’s economic miracle. A prequel of sorts to Jia’s latest film, Ash Is Purest White (2018), it follows an emo pretty boy in love triangle with the chanteuse Qiao Qiao (played by Jia’s wife and frequent collaborator Zhao Tao) and her boyfriend, a low-rent loan shark mobster.

Ennui, The Boys From Fengkuei, 1983

In contrast, Hou’s film is quiet and still compared to the barely restrained chaos of Jia’s movie. As opposed to the undercurrent of grinding industrial cacophony in Unknown Pleasures, the sound of lapping waves is an aural backdrop to most of the action in a small seaside town where group of young dudes hang out and try to find meaning in their lives. They eventually end up in Kaohshiung, the closest city to their tiny coastal burg, where more ennui and confusion awaits.

Rivers and lakes, Ash Is Purest White, 2018

Other film matchups at SFMOMA were more loosely connected—for instance, according to the programmers Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) was paired with 24 City (Jia Zhangke, 2009) for the sole reason that both films are about cities. Similarly, the programmers grouped I Wish I Knew (Jia Zhangke, 2010), Spring In A Small Town (Fei Mu, 1948), and Flowers of Shanghai (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1998), three wildly disparate movies, because they are all set in Shanghai. But the smart pairing of Johnny To’s Election (2005) and Jia’s Ash Is Purest White cleverly focused on the jiang hu, the criminal underworld in both Hong Kong and China.

Chinatown new wave, Chan Is Missing, 1982

The series also matched up Jia films with non-Asian movies, such as Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket with Jia’s Xiao Wu (a show that Jia introduced himself at SFMOMA). And props for including Chinese American director Wayne Wang’s Chan Is Missing (1982), which evokes the nouvelle vague by way of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

I’m happy that I was able to squeeze in a bunch of screenings in the mini-hiatus from editing my film, Love Boat: Taiwan, because the next four weeks or so will be solely dedicated to finishing up the movie for its world premiere in early May. More info soon on this, but please go here if you want to find out about Love Boat: Taiwan and how you can support it .

Ash Is Purest White opens theatrically on March 15 at Landmark’s Embarcadero Center Cinema in San Francisco and Landmark’s Shattuck Cinema in Berkeley, and on March 22 at AMC Mercado in Santa Clara, CNMK Fremont 8 in East Bay, and CNMK Milpitas 20 in San Jose.

Long Dark Road: 2019 Noir City film festival

Party Time, Pickup On South Street, 1953

The 2019 edition of the Noir City film festival just finished another excellent run and there was a party atmosphere for the 10-day festival as the Castro Theater hosted full houses for almost every show. As usual Noir City had value-added features including live music in between some shows, screenings of rare clips and trailers, and informative and edifying introductions by Noir City founder Eddie Muller and other knowledgable film noir geeks/authors. The movies I attended were uniformly good, but a few stood out due to the significant combination of a great cast, a strong script, and excellent direction.

Some of the festival’s offerings fell a bit short on one of the three key elements above, making for less than satisfying results. For instance, legendary director Michael Curtiz (Casablanca; Mildred Pierce) helmed The Scarlet Hour (1956) with a sure hand, and the script is classic noir, about a femme fatale and her hapless sap of a boytoy who are involved in a jewel heist. But rookie actresss Carol Omhart isn’t quite up to scratch in the lead role and despite its other strong elements the film falters on her uneven performance. Conversely, The File On Thelma Jordan (1950) includes an excellent performance from Barbara Stanwyck and moody and evocative direction by Robert Siodmak but the script’s improbable plot twists diminish the film’s overall impact.

Struggling, Nightfall, 1957

Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall (1957) is a much more successful endeavor. Although not possessing the mournful beauty of his classic noir Out of the Past, Nightfall still showed Tourneur’s strong directorial touch. The film’s two thugs, played by Brian Keith and Rudy Bond, feel truly menacing and Aldo Ray as the protagonist on the run conveys a strong sense of a man struggling to keep his bearings in the shifting sands of noir-world danger. A very young Anne Bancroft is Ray’s love interest and her performance displays a strength and gravity beyond her years. The film has just the right touch of fatalistic peril and dread to keep the viewer engaged.

Complex, Pickup On South Street, 1953

One of my favorite films of all time, Pickup On South Street (1953), was part of a trio of movies directed by Sam Fuller in this year’s festival, and it fully demonstrates a film firing on all cylinders, with acting, script, and directing all top-notch. Fuller’s kinetic directorial style and his intense, fast-paced script brilliantly complement Richard Widmark and Jean Peters’ performances as streetwise characters who are constantly maneuvering to survive. Thelma Ritter contributes a stellar performance as an aging stool pigeon, delivering a complex and emotional turn that forms the moral center of the movie.

Sultry, The Crimson Kimono, 1957

The festival also screened Fuller’s 1957 film The Crimson Kimono, which is notable for including a Japanese American character, Joe Kojaku (played with sultry subtlety by the doe-eyed James Shigeta), in a romantic lead. The film also includes a sympathetic and mostly Orientalist-free representation of the Los Angeles JA community with Nisei characters who speak in unaccented English and who are human beings instead of exotic caricatures. The film falls a bit short, however, in its analysis of race relations as it suggests that Joe’s experiences with racist microaggressions are a figment of his imagination. SPOILER: He does get the girl, however, which for mid-1950s America was pretty revolutionary.

Tense, Odds Against Tomorrow, 1959

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), a tense crime thriller produced by and starring Harry Belafonte, also possesses the magic combination of script, cast, and direction. The film shows a darker side to Belafonte’s usual upbeat persona as he plays Johnny, a nightclub singer facing dire straits due to his gambling addiction. After loan shark enforcers threaten his family with harm Johnny teams up with a couple of other shady characters including Earl, a racist from Oklahoma played by Robert Ryan, and David (Ed Begley), a fallen-from-grace cop. They three attempt to pull off a risky bank heist but the meat of the story is the strong character development of both Johnny and Earl. Director Robert Wise (West Side Story; The Sand Pebbles) delves into both characters’ personal lives to give weight and heft to what’s at stake for the two. As a result the film’s climax and conclusion are exceptionally tense and gripping. Also, unlike The Crimson Kimono, racism doesn’t get a pass in this film SPOILER and in fact Earl’s flagrant bigotry is a key culprit in the failure of the heist. END SPOILER Bonus points for supporting roles from Shelly Winters as Earl’s long-suffering girlfriend and Gloria Grahame as the sexy neighbor upstairs, as well as for the excellent score by John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The festival concluded with a pair of hard-boiled films from 1961. Sam Fuller’s third installation in this year’s festival, Underworld USA, is a bleak little number full of vengeance, double-crosses, and grudges. Cliff Robertson snarls his way through the film as a safecracker out to get the thugs who killed his dad some twenty years prior. With almost no redeeming characters the film is an existential ode to the shady side of life, where the only motivations are revenge and survival.

Twisted, Blast of Silence, 1961

The festival closed with the excellent and underappreciated Blast of Silence, a low-budget gem directed with a stylish and jaded eye by Allen Baron. Baron also stars as Frankie Bono, a creepy hitman who presages Travis Bickle in his angst-ridden interior monolog and his twisted, affectless approach to killing. The film follows Frankie as he plots his next hit and depicts his sad and stilted attempts to make meaningful human contact beyond his gruesome professional responsibilities. Bleak, hard-boiled, and grim, and set in the dead of winter between Christmas and New Year’s day, Blast of Silence is like an icy slap of cold air on a winter’s day.

Once You Get Started: Frameline 42 Film Festival

Tapestry, Yours In Sisterhood, 2018

Like Hong Kong, San Francisco is an excellent city for film-viewing, and with Frameline (official title: San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival) in full swing this week I suddenly feel like there are not enough hours in the day to see all of the movies I want to see. But I’m valiantly carrying on despite the burden of sorting through and prioritizing the festival’s ridiculously stacked schedule. A few highlights from my Frameline viewings this week include three outstanding documentaries and a narrative that demonstrate the high bar of the festival’s stellar programming this year.

Mixing it up, Yours In Sisterhood, 2018

Irene Lusztig’s documentary Yours In Sisterhood has a simple premise. Back in the 1970s thousands of women wrote letters to Ms. Magazine, the premiere mainstream feminist publication of the day, but due to space restrictions only a handful of those letters were published. The rest reside in an archive at Radcliffe University that Lusztig accessed some years ago. From that archive she chose about 300 letters and then found women from the same locales as the original writers to re-read the letters on camera—from those 300-odd readings she chose twenty-seven for the film. The results are a brilliant tapestry of 1970s feminism and the resonances from that era to the present day. Lusztig presents the first several of the re-readings straight up to the camera without commentary, then gradually embroiders this format, showing the responses of the modern-day readers to their 1970s counterparts’ missives. A handful of the letters are reread by their original authors as well, including a particularly poignant coming-out letter written by a woman who was sixteen in the 1970s. After reading her letter she recalls how at the time she thought that being queer meant that she would be lonely all her life and that she would never marry or have children. Happily, this bleak prediction did not come to pass as the woman reveals that in the intervening years she and her longtime partner have raised two children and are well-liked in their small-town community.

Lusztig also provides a bit of dyke fanservice by including lesbian author Deena Metzger reading her 1970s letter onscreen, which was cheered loudly at the Frameline screening I attended. A minor quibble: the film includes only one Asian American woman and one Latina, which I understand reflects the mostly-white demographics of the Ms. Magazine readership back in the day. But other than that Lusztig does a great job mixing up the optics of the film and presenting a diverse range of points of view.

Imbalance of power, Call Her Ganda, 2018

PJ Raval’s documentary Call Her Ganda follows the case of the murder of transgender Filipina Jennifer Laude, who was killed in a fit of gay panic by US Marine Joseph Scott Pemberton. Despite being convicted of the crime Pemberton was shielded from imprisonment by the US government, much to the outrage of the Filipino populace in general and the transgender community in particular. Raval’s film explicates the fraught history of the United States and the Philippines, using Laude’s case as an example of history of colonialism and the imbalance of power between the two countries. The film’s gliding camerawork effectively captures the glowing lights of Olongapo City by night and its hodgepodge of street markets, as well as the utilitarian bleakness of US military bases in the Philippines, which has long been exploited by the US due to its strategic location in the Pacific theater.

By focusing on the grassroots activism surrounding Laude’s murder Raval’s film recalls seminal Asian Pacific American documentaries such as Who Killed Vincent Chin? and The Fall of the I-Hotel which similarly depict the empowerment of the API community in the face of systemic injustices.

Vibrant, When The Beat Drops, 2018

Jamal Sims’ exuberant documentary When The Beat Drops is a vibrant celebration of bucking, or j-setting, a dance form originating in the black gay community in Atlanta. Based on moves from female cheerleading squads at historically black colleges and universities, in particular the cheer squad from Jackson State University, bucking primarily takes place in gay clubs throughout the south and southeast United States.

The movie helps to explode definitions of what makes a man and the fluidity of the various characters is breathtaking and effortless. It’s beautiful to see men so confident in their maleness that they are able to demolish the gender binary and let the many facets of their identity shine through. Added to that are some dope AF dance sequences, in clubs, in competitions, and en la calle, that strikingly depict the dynamism and creativity of the j-setting scene. I especially love the fact that the bucking competitions shown in the film are judged by some of the female cheer squad members whose routines j-setting pays homage to.

Perspective, Retablo, 2018

Álvaro Delgado-Aparicio’s Retablo is a beautifully told narrative that further explores the boundaries of masculinity, this time through the lens of a Peruvian family in the Andes. Delgado-Aparicio beautifully uses the cinematic grammar to underscore the mindset of Segundo, his young protagonist, who inadvertently finds out an uncomfortable truth about his father Noe. Noe is a master artisan who is training Segundo to create retablos, three-dimensional tableaux that act as family portraits, as devotionals, and as representations of significant events in their small Andean village. In the first part of the film Segundo’s worldview is stable and stationary, framed almost exclusively in master shots, which echoes the proscenium framing of the Noe and Segundo’s retablos. Once Segundo learns about his father’s clandestine trysts with other men the film’s framing and editing become more jagged and abrupt, reflecting Segundo’s unsettled state of mind. Delgado-Aparicio’s limited use of conventional tight shots and point-of-view shots in the first part of the film also pays off when he finally frames a key moment in the film in close-up from Segundo’s vantage point. The impact is shattering, reflecting the moment’s effect on Segundo’s previously limited perspective.

Retablo also explicates the village’s cultural taboos around same-sex relationships by emphasizing the hypermasculinity of Segundo’s friend Mardonio, whose bragaddocio possibly masks his insecurity about his own sexuality. Segundo and Mardonio enact a classic homoerotic triangle with local shopowner Felicita as Mardonio crudely sexualizes Felicita in order to deny his attraction to Segundo. The film’s dialog in both Spanish and Ayacucho Quechua, one of the most widely spoken Andean dialects in Peru, also lends an immediacy to the film.

Intimate, We The Animals, 2018

Still to come this week at Frameline: big, showy titles including those focusing on queer superstars Emily Dickinson (Wild Nights With Emily), Alexander McQueen (McQueen)and Robert Mapplethorpe (Mapplethorpe), the Chloë Grace Moretz vehicle The Miseducation of Cameron Post, and the closing night doc Studio 54, about the legendary New York City disco of the same name, the ever-popular shorts programs Fun In Girls Shorts and Fun In Boys Shorts, and smaller, more intimate movies such as the Sundance favorite We The Animals and the UK/Spain co-production Anchor And Hope, (starring #HarryPotter alumna Natalia Tena). I’m hoping to make it to most of these shows since I love me a good film festival, and this year’s Frameline is one of the best.

Thinking Out Loud: 2018 San Francisco International Film Festival

Paternalism, Angels Wear White, 2017

The San Francisco International Film Festival is in full swing right now and as usual the fest has a great lineup of world cinema. Although my viewing schedule was very truncated due to life circumstances I still had a quality film festival experience over the first weekend.

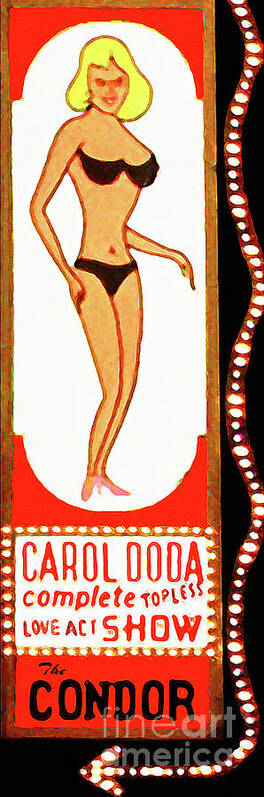

Compassionate, The Third Murder, 2017

I started my mini-marathon with Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest film, The Third Murder. As per usual Kore-eda goes directly to the psychological heart of his characters, examining their motivations without judgment or prejudice. In The Third Murder a seemingly straightforward homicide investigation takes several unpredictable turns and eventually leads down many unexpected paths. Almost every character presents an unreliable point of view, contributing to the many shades of gray of complicity and blame. Yet Kore-eda emphasizes the compassionate over the judgmental and the film’s open-ended conclusion questions assumptions of guilt and innocence.

The Third Murder is beautifully lit and shot, with Kore-eda using gliding zooms and slow pans to delineate the cinematic space. The film also makes great use of reflection and mirroring to suggest complicity and transference of guilt, since almost everyone in the film lies at one point or another. Performances are also on point, led by the ever-awesome Yakusho Koji (Shall We Dance? The Eel) as the man accused of murder, and the dapper Fukuyama Masaharu (Like Father, Like Son) as the lawyer assigned to the case who begins to doubt everything and everybody as the film progresses.

Vulnerable, A Man of Integrity, 2017

I continued my festival viewing with A Man Of Integrity, by Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof. Like his compatriot Jafar Panahi, Rasoulof has been arrested in his home country and banned from making films, so A Man Of Integrity was shot on the down-low in a wintry northern area of Iran. The film is a bitter and intense drama about a family settled in a remote Iranian village that comes face to face with the town’s intractable corruption and cronyism. The delicate and vulnerable goldfish that they farm become a metaphor for the family’s tenuous status in the town, and the film is grounded in strong and intense performances by Reza Akhlaghirad and Soudabeh Beizaee as the couple who stand up to corruption in the village.

Power dynamics, Angels Wear White, 2017

Vivian Qu’s Angels Wear White also looks at corruption and power dynamics, this time in a seaside village in China. It’s a gripping narrative about the aftermath of an assault on two schoolgirls and the reverberations of that crime on its small-town location. Director Qu captures the precarious position of the female characters in the film, most of whom are suffering under a sexist and paternalistic system, and she brings out great performances from both the adults and the preteen and teenage actors. Also of note is the film’s excellent editing which moves the story along at a steady and assured pace.

Obscured, The White Girl, 2017

The White Girl features some beautiful cinematography by the legendary cameraman Christopher Doyle (Chungking Express), who co-directed the film with Jenny Suen. Set in one of the last fishing villages in Hong Kong, the film follows a young woman known for her very pale complexion that she protects religiously, supposedly due to her allergy to sunlight. Along the way she encounters a mysterious dude (Joe Odagiri) who lives in a ruined building that is also a camera obscura. Added to mix is an evil developer who wants to pave over the cute fishing village and a subplot involving the white girl’s mother, a famous singing star who long ago abandoned her partner and daughter. The film is heavy with allegory about Hong Kong’s current struggles with China and is a little too elliptical for my taste, but it’s always a pleasure to hear Cantonese dialog.

Struggles, Minding The Gap, 2018

I rounded off my viewings with Bing Liu’s Minding The Gap, which blends character-driven verite with personal documentary. The film follows Liu and two of his skateboarding friends who talk about surviving life in Rockford, a picturesque city about 1.5 hours outside of Chicago that in fact suffers from a high crime rate, most of which is due to domestic violence. The film becomes cathartic for its three distinct and sympathetic characters, including Liu himself, revealing the struggles each encounters in reconciling their painful histories with their current lives. It’s the kind of humanistic doc that Kartemquin Films (which executive-produced the film) is known for, their most famous film being Hoop Dreams. Minding The Gap is good, solid documentary filmmaking that isn’t afraid to touch on difficult topics like alcoholism, wife beating, and child abuse.

Also upcoming this week—the US premiere of John Woo’s latest actioner Manhunt, which may or may not be a return to his past heroic bloodshed glory, Sandi Tan’s personal documentary Shirkers, Hong Sang Soo’s latest Claire’s Camera, and Lee Anne Schmitt’s essay film Purge This Land, among many other cinematic treats.

for tickets and more information go here

Get Ur Freak On: Favorite Movies of 2017

My favorite films from 2017 made the list for a variety of reasons but these are the movies I most enjoyed from last year. Three of the films were theatrically released in 2016 but I viewed them first at the Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) in 2017 so I’m including them here. I saw Get Out and The King on plane flights, but the rest I watched in a cinema somewhere. Listed in no particular order.

Pulchritude, Jung Yonghwa and Nicholas Tse, Cook Up A Storm, 20171

1. Cook Up A Storm: This film is on the list for the purely aesthetic pleasure of seeing Jung Yonghwa’s perfect features on the big screen. There’s also a lot of nice food porn cinematography but the movie itself is quite lightweight and if it didn’t star my boy Yonghwa (as well as the equally photogenic Nicholas Tse) I’m not sure I would have even given it the time of day. But I’m a big fan of pulchritude so I’m putting it on my list.

Emo, Lee Byung Hun, The Fortress, 20172.

2. The Fortress: Lee Byung Hun rehabilitates his public image completely in Hwang Dong Hyuk’s absorbing and emo historical about a famously tragic moment in Korean history. While Lee is brilliant as the courtier who must make an unbearable moral choice the rest of the cast is also excellent, including Kim Yoon Seok as Lee’s counterpart, the equally conflicted royal advisor who also pays a heavy price for his decisions.

Wary, Song Kang Ho, A Taxi Driver, 2017

3. A Taxi Driver: Song Kang Ho is solid as usual in director Jang Hoon’s retelling of the 1980 Gwang Ju uprising, in which the repressive government brutally put down student protestors in the southern Korean city. Although the film doesn’t shy away from the political ramifications of the story it’s still very character-driven, as Song’s wary taxi driver gradually comes around to the side of justice and truth. Bonus points for a dope car chase that turns spunky taxicabs into vehicles for the resistance.

Indistinguishable, Jung Woo Sung, The King, 2017

4. The King: The third South Korean film on this list attests to the strength and diversity of that country’s commercial film industry. Han Jae Rim’s brutal and cynical political thriller, in which the gangsters are indistinguishable from the lawyers and politicians supposedly opposing them, includes a great performance from rising star Ryu Jun-yeol, who also had a strong supporting role in A Taxi Driver.

Complicit, Mon Mon Mon Monsters, 2017

5. Mon Mon Mon Monsters: Giddens Ko’s horror film/teen movie presents a nightmare high school scenario where no one is innocent and everyone is complicit. As he stated in his introduction to the film at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, who is the real monster in the movie?

Fierce, James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, 2016

6. I Am Not Your Negro: Raoul Peck’s doc about the legendary James Baldwin shines when it connects the dots between past and present racism in the U.S. Although Samuel Jackson’s does a fine job narrating the film, he is easily upstaged by archival footage of Baldwin himself fiercely speaking out about race, politics, and the historical and contemporary struggles of African Americans. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at HKIFF.

Tensions, Justin Chon, Gook, 2017

7. Gook: Justin Chon’s indie gem presents the Korean American perspective on sa-i- gu, the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles following the acquittal of the Wind, Powell, Koons, and Briseno, the four police officers caught on video beating motorist Rodney King. Chon miniaturizes the conflicts of the time and his film effectively captures the racial tensions of that moment in time.

Lovely, Cinema, Manoel de Oliveira and Me, 2017

8. Cinema, Manoel de Oliveira and Me: An outstanding essay film directed by João Botelho, one of the influential Portuguese film director’s protégés. The film looks at the relationship between the late director and Botelho and concludes with a lovely restaging of one of Oliviera’s unfinished silent films.

Ellipses, Taraneh Alidoosti and Shahad Hosseini, The Salesman, 2017

9. The Salesman: Director Asghar Farhadi creates another humanistic look at moral ambiguity and human frailty. As in A Separation (2011), his use of narrative ellipses and architectural metaphors is masterful, as is his ability to draw out strong and sympathetic, vividly shaded performances from his cast. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at HKIFF.

Unexpected, Window Horses, 2017

10. Window Horses: Another excellent animated feature from Ann Marie Fleming (The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam, 2003), this time following a young Iranian-Chinese Canadian poet named Rose as she travels to her father’s home country for a poetry festival. Yes! Totally fun, unexpected and imaginative, with a gorgeous blend of hand-drawn and digitally generated animation.

Bleak,Tadanobu Asano, Harmonium, 2017

11. Harmonium: an utterly bleak family drama in the tradition of Tokyo Sonata, Koji Fukada’s movie shows the catastrophic consequences of a few bad life decisions. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at CAAMfest.

Bravura, Youth, 2017

12. Youth: Feng Xiaogang’s look at a theater troupe in Cultural Revolution China uses a familiar trope of the youth romance film—the awkward country bumpkin outsider rebuffed in her attempts to join an elite, more sophisticated group–to cleverly investigate the deeper political and social elements dividing the country at the time. Utilizing his familiar bravura filmmaking style, including swooping camerawork and intense and masterfully conducted battle scenes, Feng never loses his focus on the impact of great historical events and social movements on ordinary human beings.

Unease, Terry Notary, The Square, 2017

13. The Square: Ruben Ostlund kicks up the social commentary a notch from Force Majeure (2014), and The Square is an even better film about male anxiety and weakness than its predecessor. Ostland is a master at inverting cinematic conventions and manipulating sound, image and editing to create maximum awkwardness, discomfort and unease.

Horrors, LaKeith Stanfield, Get Out, 2017

14. Get Out: A brilliant brilliant movie that proves that commercial genre films can be as significant as any other art form in capturing the zeitgeist of a moment in time and place. Director Jordan Peele utilizes the horror genre to reveal the true horrors in the U.S., where racism and oppression lie just below the surface of seemingly benign everyday gentility.

Rebel Without A Pause: Why we need GOOK

The Korean American view, GOOK, 2017

Just caught a matinee of Justin Chon’s film GOOK at the Alamo Drafthouse here in San Francisco. Although the movie is a bit rough around the edges for the most part it’s an absorbing and successfully mounted film that focuses on the Korean American perspective of a particularly fraught moment in US history.

The film follows Eli and Daniel, a pair of Korean American brothers who run a small and funky shoe store in Paramount, an unincorporated area bordering South Central Los Angeles. It’s set during the civil unrest in Los Angeles in 1992 following the acquittal of the four LAPD officers caught on camera beating unarmed motorist Rodney King, but most of that action takes place offscreen. Instead the film miniaturizes the conflicts that occurred during that time, focusing on a small group of individuals repping for the entire city of Los Angeles. Several times characters refer to action taking place in South Central but aside from a few digitally added columns of smoke on the distant horizon we don’t actually see any widespread violence. This is no doubt in part due to the film’s indie budget which probably precluded any large-scale set pieces of buildings on fire or shit getting fucked up. So we get a couple broken windows, some beatdowns, a few guns being fired into the air, and other incidents that gesture toward the greater unrest without actually staging any of the mass devastation and destruction that took place during that time.

Time and place, GOOK, 2017

Justin Chon does a good job with his actors (himself included) and demonstrates that he has an eye for time and place in the worn-out, working class neighborhood he places his story in. He’s also got the 1990s kicks fetish down pat as one of the narrative threads turns on the acquisition of several pairs of expensive sneakers. The film’s art direction also works hard, with baggy jeans, overalls, and asymmetrical jheri-curl hairstyles capturing the period’s fashion sensibilities. Although I have some issues with the resolution of the character arc of Kamilla, the young African American teen who befriends Eli and Daniel, for the most part Chon directs with a steady hand and maintains a tone of tense wariness in the film’s multiethnic milieu.

And like MOONLIGHT, which the film in some way resembles, there are no white people in the movie, which attests to the racial and social stratification that led to the explosion of tensions in 1992 following the verdict that acquitted Officers Powell, Wind, Koons, and Briseno of beating Rodney King. Instead the film tells its story from a Korean American POV, one which has for the most part been lacking in mainstream depictions of the 1992 unrest. This omission is especially glaring considering the fact that the Korean American community suffered huge property losses during the unrest and that sa-i-gu, or April 29, is considered a watershed moment in the Korean American community.

Important, GOOK, 2017

Even in the 21st century the focus on a Korean American perspective is especially important, and this was all the more apparent to me after watching the ads and trailers that preceded GOOK’s screening at the Alamo. The cinema is a hipster haven located in what used to be a predominantly Latino neighborhood, and I counted exactly one non-white person in the many trailers for the various indie films in the upcoming schedule. Likewise, the ironic midcentury aesthetic of the found footage in-house announcements were decidedly not very diverse. One short clip featured an all-white group of young people from the early 1960s dancing to African American style choreography. This moment was presented without a hint of irony and its glaring cultural appropriation felt decidedly tone-deaf.

So even though I feel like I say this a lot, it clearly bears repeating. Unconscious Eurocentric bias makes it all the more important to support films like GOOK. Now more than ever, as Trumpism threatens to turn back the hard-fought gains of the civil rights movement and its struggles for equality and social justice, we have to keep decentering the master narratives of white hegemony and bring Asian American voices to the fore.

Recent Comments