Posts tagged ‘chinese movies’

Let It Shine: 2023 San Diego Asian Film Festival

Just got back from a quick and dirty one-day trip to San Diego to attend the San Diego Asian Film Festival (SDAFF). SDAFF is the biggest film fest in North America focusing on Asian/American films and artistic director Brian Hu and his team consistently program an outstanding blend of art house, genre, and indie films. Since I ride for Lee Byung-hun, I got the impetus for my trip when I found out that SDAFF was screening his latest film, CONCRETE UTOPIA (which is also South Korea’s entry in the upcoming Academy Awards). I had a bit of airline credit I had to use by the end of the year, plus a few points to spend on a rental car and a hotel so I made the decision to take a jaunt to sunny San Diego.

I arrived Sunday morning just in time to have some excellent chicken jook and to see a few friends at the filmmakers’ brunch. SDAFF is known for its great hospitality and this year was no exception. Then it was off to the movies, starting with the shorts program Astral Projections. MANY MOONS (dir. Chisato Hughes) was the standout film in this program, an essay film about the 1880s forced expulsion of almost the entire Chinese population of Humboldt county. Since I’d made THE CHINESE GARDENS about a similar occurrence up in Port Townsend Washington back in 2013 the topic was of particular interest to me. Hughes did a great job layering interviews, text. archival images, and other visual elements to question the facts and fictions around this notorious event.

After another pit stop at the reception area for a couple slices of pizza and some butter cookies I then saw the nouveau martial arts film 100 YARDS. Set in 19th century Tianjian, the film is co-directed by Xu Junfeng and Xu Haofang, who’s known for writing Wong Kar-Wei’s THE GRANDMASTER, and this movie similarly attempts to re-imagine and revisit the martial arts genre, but with less success. Although the smoky greys and browns of the mis en scene create a striking visual tableau and the costumes, props and set design were all great, there were way too many fights and not enough character development to hold my interest. It was hard for me to care much about the main character’s daddy issues, although Jacky Heung and Andy On brought the skilz to their fight scenes.

I then moved on to Yu Gu’s documentary, EAST WEST PLAYERS: A HOME ON STAGE. As Gu notes, she had less than an hour to cover nearly sixty years of the history of the legendary and influential Los Angeles-based Asian American theater company, but the film does an excellent job of doing just that. Gu pairs older and newer veterans of EWP such as George Takei, Daniel Dae Kim, James Hong, Tamlyn Tomita, and John Cho to discuss the significance of the troupe as a voice for Asian Americans in the theater. It was fun to see clips from the trove of archival footage of EWP as well.

By then I was contemplating how I would squeeze in time to grab a bite for dinner but decided to forgo eating to line up for the main event of my trip, CONCRETE UTOPIA. I first heard about this movie from my friend Anthony Yooshin Kim, who’d seen it at CGV in Los Angeles a few weeks prior. Unfortunately at that time there were no plans for a wider theatrical release in the US so when SDAFF announced it as part of its lineup I decided to catch it there, since I wanted to see it on the big screen. A dystopic story about the residents of the only apartment building left standing after a massive earthquake levels Seoul and starring A-listers including my man Lee Byung-hun, Park Bo-young, and Park Seo-jun (who makes his US debut in THE MARVELS this year), the movie did not disappoint. The film has everything that makes South Korean cinema so pleasurable—outstanding special effects, brilliant acting, imaginative storytelling, well-drawn, complex characters, and sharp social critique. Lee Byung-hun does an outstanding job modulating his character, making his narration arc compelling and believable. Park Seo-jun and Park Bo-young are also great as a young couple whose lives and values are literally shaken up and turned upside down by the catastrophe. Despite its fantastical premise the movie never wavers in its examination of humanity under extreme duress.

CODA: This past week I had the fangirl pleasure of joining a zoom press conference for CONCRETE UTOPIA that featured Lee Byung-Hun and director Um Tae-hwa. It was fun to share the same virtual space as Lee, even if we didn’t directly interact. I tried to restrain my cyberstalker stanning as best I could but I’m not sure if I was entirely successful. CONCRETE UTOPIA is set to open in New York and Los Angeles on Dec. 8, and will go into wide release across North America the following weekend.

Forever Waiting: SFFILM’s Hong Kong Cinema series

SFFILM’s annual Hong Kong cinema series happened this weekend and it’s a really interesting look at the state of the territory’s movie industry today. Included were the edgy neo-noir G-Affairs, the character-driven feel-good sports movie Men on the Dragon, and Pang Ho-Cheung’s irreverent Lunar New Year quickie Miss Behavior, among a selection of other films.

This year’s series was held at the Roxie Theater in the Mission and for me it was full circle since I saw my very first of many many Hong Kong movies, A Chinese Ghost Story, at the Roxie on the big screen back in the late 1980s. But the Hong Kong movie world has changed immeasurably from 1986 to 2019 and those changes are reflected in the programming at this year’s Hong Kong cinema series.

Although Hong Kong cinema has had its share of ups and downs since its heyday in the 1990s, ironically that may have led more opportunities for creative exploration. Though the high-powered star system might no longer exist there are still great films being made that go beyond Hong Kong’s iconic crime film, wuxia, and martial arts genres. This year’s showcase is perhaps indicative of a renaissance in Hong Kong’s filmmaking community that is less about glitzy commercial films and more about developing a healthy independent film scene. This is especially true since co-productions with China are so heavily controlled by the PRC’s censorship board. Though there may be less money for non-co-productions that focus on the local Hong Kong audience, in some ways these films are a truer reflection of Hong Kong’s distinctive cultural milieu and it’s good to see younger filmmakers leading the way.

Jun Li’s Tracey follows the story of a middle-aged man who comes out to his friends and family about being transgender. The movie sensitively explores the topic and is driven by outstanding performances by veteran actors Philip Keung as Tai-hung/Tracey and Kara Wai as Anne, his stricken wife. Keung is excellent as the transperson who is finally realizing she can become who she really is. I’ve always liked Keung as one of Hong Kong’s stalwart character actors but he’s really next level in Tracey, with his sensitive and mobile face expressing a world of hurt and wonder. Wai likewise sketches a complex portrayal of a character that in lesser hands could have easily been one-dimensional and the two of these powerhouse actors are at their best when in their intense scenes together. Wai also has nice moments with Ng Siu Hin (Mad World; Ten Years) as Tai-hung and Anne’s son, a young man who ostensibly advocates for sexual freedom and understanding but who has to confront his own biases when the abstract becomes concrete in his own father’s situation.

The film is somewhat episodic and it sometimes feels like first-time feature film director Li is hoping to cram a lot of ideas into a two-hour film. But his ambitious debut speaks to a thoughtful and restless creativity that wants to say a lot, which in less sensitive and sympathetic hands might have been a simplified, dumbed down, or sensationalized film.

Jessey Tsang’s The Lady Improper looks at questions of female sexuality, agency, and control. Lead performer Charlene Choi got her start as one half of the mega-superstar singing duo The Twins but she’s since become one of Hong Kong’s most reliable leading ladies in her selection of challenging and complex roles. In The Lady Improper she again has chosen a film that pushes boundaries as Choi plays Siu Man, an unhappily married woman who takes control of her unsatisfying life

Throughout the film director Tsang emphasizes the importance of Siu Man taking charge of her life, as opposed to letting others control her. She stands up to family criticisms, changes her career path, addresses her insecurities about physical intimacy, and ultimately decides how her life should be. In this way Tsang’s perspective as a female filmmaker is clear, as she portrays the answers to her protagonist’s dilemmas as reliant on Siu Man, not on outside forces. The film’s depiction of Siu Man’s empowerment is deeply feminist in its insistence on the importance of women deciding for themselves the path their lives will take.

CODA: though not a Hong Kong film, I capped off my weekend by seeing Long Day’s Journey Into Night (Bi Gan, 2017). The film was in limited release here in the States a few months ago but I was in editing hell and missed it, so I was glad for the chance to see it on the big screen and in 3D at the venerable Castro Theater here in San Francisco. Suffice to say that the film didn’t disappoint in its surreal portrayal of a brooding man searching for a mysterious woman, which is of course a classic noir theme. Here director Bi puts a decidedly Chinese spin on it, locating the story in Kaili City, located in the landlocked and somewhat economically depressed southeastern province of Guizhou. Bi uses local dialect, a gorgeous lighting design, and an elliptical narrative structure to suggest the ennui and dislocation of his characters. The film concludes with an outstanding 59-minute-long single-take unedited shot, screened at the Castro in 3D, that may or may not be a dream sequence and that includes cow skulls, ping pong, spooked horses, characters flying, and fireworks among many other amazing images that combine to evoke an altered state. The sequence is totally rad and totally breathtaking. I’m so glad I got to see this in a proper cinema and not on my laptop or on the back of an airplane seat.

CODA2: Hong Kong stalwart Herman Yau’s latest action movie The White Storm 2: Drug Lords is also playing at my multiplex this weekend so I’m going to try to see it too. Way to round off a great weekend of movie-watching!

Thinking Out Loud: 2018 San Francisco International Film Festival

Paternalism, Angels Wear White, 2017

The San Francisco International Film Festival is in full swing right now and as usual the fest has a great lineup of world cinema. Although my viewing schedule was very truncated due to life circumstances I still had a quality film festival experience over the first weekend.

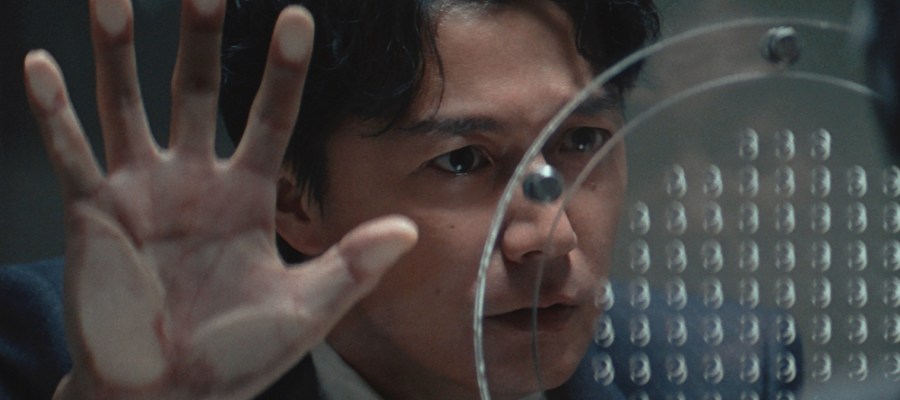

Compassionate, The Third Murder, 2017

I started my mini-marathon with Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest film, The Third Murder. As per usual Kore-eda goes directly to the psychological heart of his characters, examining their motivations without judgment or prejudice. In The Third Murder a seemingly straightforward homicide investigation takes several unpredictable turns and eventually leads down many unexpected paths. Almost every character presents an unreliable point of view, contributing to the many shades of gray of complicity and blame. Yet Kore-eda emphasizes the compassionate over the judgmental and the film’s open-ended conclusion questions assumptions of guilt and innocence.

The Third Murder is beautifully lit and shot, with Kore-eda using gliding zooms and slow pans to delineate the cinematic space. The film also makes great use of reflection and mirroring to suggest complicity and transference of guilt, since almost everyone in the film lies at one point or another. Performances are also on point, led by the ever-awesome Yakusho Koji (Shall We Dance? The Eel) as the man accused of murder, and the dapper Fukuyama Masaharu (Like Father, Like Son) as the lawyer assigned to the case who begins to doubt everything and everybody as the film progresses.

Vulnerable, A Man of Integrity, 2017

I continued my festival viewing with A Man Of Integrity, by Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof. Like his compatriot Jafar Panahi, Rasoulof has been arrested in his home country and banned from making films, so A Man Of Integrity was shot on the down-low in a wintry northern area of Iran. The film is a bitter and intense drama about a family settled in a remote Iranian village that comes face to face with the town’s intractable corruption and cronyism. The delicate and vulnerable goldfish that they farm become a metaphor for the family’s tenuous status in the town, and the film is grounded in strong and intense performances by Reza Akhlaghirad and Soudabeh Beizaee as the couple who stand up to corruption in the village.

Power dynamics, Angels Wear White, 2017

Vivian Qu’s Angels Wear White also looks at corruption and power dynamics, this time in a seaside village in China. It’s a gripping narrative about the aftermath of an assault on two schoolgirls and the reverberations of that crime on its small-town location. Director Qu captures the precarious position of the female characters in the film, most of whom are suffering under a sexist and paternalistic system, and she brings out great performances from both the adults and the preteen and teenage actors. Also of note is the film’s excellent editing which moves the story along at a steady and assured pace.

Obscured, The White Girl, 2017

The White Girl features some beautiful cinematography by the legendary cameraman Christopher Doyle (Chungking Express), who co-directed the film with Jenny Suen. Set in one of the last fishing villages in Hong Kong, the film follows a young woman known for her very pale complexion that she protects religiously, supposedly due to her allergy to sunlight. Along the way she encounters a mysterious dude (Joe Odagiri) who lives in a ruined building that is also a camera obscura. Added to mix is an evil developer who wants to pave over the cute fishing village and a subplot involving the white girl’s mother, a famous singing star who long ago abandoned her partner and daughter. The film is heavy with allegory about Hong Kong’s current struggles with China and is a little too elliptical for my taste, but it’s always a pleasure to hear Cantonese dialog.

Struggles, Minding The Gap, 2018

I rounded off my viewings with Bing Liu’s Minding The Gap, which blends character-driven verite with personal documentary. The film follows Liu and two of his skateboarding friends who talk about surviving life in Rockford, a picturesque city about 1.5 hours outside of Chicago that in fact suffers from a high crime rate, most of which is due to domestic violence. The film becomes cathartic for its three distinct and sympathetic characters, including Liu himself, revealing the struggles each encounters in reconciling their painful histories with their current lives. It’s the kind of humanistic doc that Kartemquin Films (which executive-produced the film) is known for, their most famous film being Hoop Dreams. Minding The Gap is good, solid documentary filmmaking that isn’t afraid to touch on difficult topics like alcoholism, wife beating, and child abuse.

Also upcoming this week—the US premiere of John Woo’s latest actioner Manhunt, which may or may not be a return to his past heroic bloodshed glory, Sandi Tan’s personal documentary Shirkers, Hong Sang Soo’s latest Claire’s Camera, and Lee Anne Schmitt’s essay film Purge This Land, among many other cinematic treats.

for tickets and more information go here

Get Ur Freak On: Favorite Movies of 2017

My favorite films from 2017 made the list for a variety of reasons but these are the movies I most enjoyed from last year. Three of the films were theatrically released in 2016 but I viewed them first at the Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) in 2017 so I’m including them here. I saw Get Out and The King on plane flights, but the rest I watched in a cinema somewhere. Listed in no particular order.

Pulchritude, Jung Yonghwa and Nicholas Tse, Cook Up A Storm, 20171

1. Cook Up A Storm: This film is on the list for the purely aesthetic pleasure of seeing Jung Yonghwa’s perfect features on the big screen. There’s also a lot of nice food porn cinematography but the movie itself is quite lightweight and if it didn’t star my boy Yonghwa (as well as the equally photogenic Nicholas Tse) I’m not sure I would have even given it the time of day. But I’m a big fan of pulchritude so I’m putting it on my list.

Emo, Lee Byung Hun, The Fortress, 20172.

2. The Fortress: Lee Byung Hun rehabilitates his public image completely in Hwang Dong Hyuk’s absorbing and emo historical about a famously tragic moment in Korean history. While Lee is brilliant as the courtier who must make an unbearable moral choice the rest of the cast is also excellent, including Kim Yoon Seok as Lee’s counterpart, the equally conflicted royal advisor who also pays a heavy price for his decisions.

Wary, Song Kang Ho, A Taxi Driver, 2017

3. A Taxi Driver: Song Kang Ho is solid as usual in director Jang Hoon’s retelling of the 1980 Gwang Ju uprising, in which the repressive government brutally put down student protestors in the southern Korean city. Although the film doesn’t shy away from the political ramifications of the story it’s still very character-driven, as Song’s wary taxi driver gradually comes around to the side of justice and truth. Bonus points for a dope car chase that turns spunky taxicabs into vehicles for the resistance.

Indistinguishable, Jung Woo Sung, The King, 2017

4. The King: The third South Korean film on this list attests to the strength and diversity of that country’s commercial film industry. Han Jae Rim’s brutal and cynical political thriller, in which the gangsters are indistinguishable from the lawyers and politicians supposedly opposing them, includes a great performance from rising star Ryu Jun-yeol, who also had a strong supporting role in A Taxi Driver.

Complicit, Mon Mon Mon Monsters, 2017

5. Mon Mon Mon Monsters: Giddens Ko’s horror film/teen movie presents a nightmare high school scenario where no one is innocent and everyone is complicit. As he stated in his introduction to the film at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, who is the real monster in the movie?

Fierce, James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, 2016

6. I Am Not Your Negro: Raoul Peck’s doc about the legendary James Baldwin shines when it connects the dots between past and present racism in the U.S. Although Samuel Jackson’s does a fine job narrating the film, he is easily upstaged by archival footage of Baldwin himself fiercely speaking out about race, politics, and the historical and contemporary struggles of African Americans. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at HKIFF.

Tensions, Justin Chon, Gook, 2017

7. Gook: Justin Chon’s indie gem presents the Korean American perspective on sa-i- gu, the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles following the acquittal of the Wind, Powell, Koons, and Briseno, the four police officers caught on video beating motorist Rodney King. Chon miniaturizes the conflicts of the time and his film effectively captures the racial tensions of that moment in time.

Lovely, Cinema, Manoel de Oliveira and Me, 2017

8. Cinema, Manoel de Oliveira and Me: An outstanding essay film directed by João Botelho, one of the influential Portuguese film director’s protégés. The film looks at the relationship between the late director and Botelho and concludes with a lovely restaging of one of Oliviera’s unfinished silent films.

Ellipses, Taraneh Alidoosti and Shahad Hosseini, The Salesman, 2017

9. The Salesman: Director Asghar Farhadi creates another humanistic look at moral ambiguity and human frailty. As in A Separation (2011), his use of narrative ellipses and architectural metaphors is masterful, as is his ability to draw out strong and sympathetic, vividly shaded performances from his cast. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at HKIFF.

Unexpected, Window Horses, 2017

10. Window Horses: Another excellent animated feature from Ann Marie Fleming (The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam, 2003), this time following a young Iranian-Chinese Canadian poet named Rose as she travels to her father’s home country for a poetry festival. Yes! Totally fun, unexpected and imaginative, with a gorgeous blend of hand-drawn and digitally generated animation.

Bleak,Tadanobu Asano, Harmonium, 2017

11. Harmonium: an utterly bleak family drama in the tradition of Tokyo Sonata, Koji Fukada’s movie shows the catastrophic consequences of a few bad life decisions. Released 2016, viewed in 2017 at CAAMfest.

Bravura, Youth, 2017

12. Youth: Feng Xiaogang’s look at a theater troupe in Cultural Revolution China uses a familiar trope of the youth romance film—the awkward country bumpkin outsider rebuffed in her attempts to join an elite, more sophisticated group–to cleverly investigate the deeper political and social elements dividing the country at the time. Utilizing his familiar bravura filmmaking style, including swooping camerawork and intense and masterfully conducted battle scenes, Feng never loses his focus on the impact of great historical events and social movements on ordinary human beings.

Unease, Terry Notary, The Square, 2017

13. The Square: Ruben Ostlund kicks up the social commentary a notch from Force Majeure (2014), and The Square is an even better film about male anxiety and weakness than its predecessor. Ostland is a master at inverting cinematic conventions and manipulating sound, image and editing to create maximum awkwardness, discomfort and unease.

Horrors, LaKeith Stanfield, Get Out, 2017

14. Get Out: A brilliant brilliant movie that proves that commercial genre films can be as significant as any other art form in capturing the zeitgeist of a moment in time and place. Director Jordan Peele utilizes the horror genre to reveal the true horrors in the U.S., where racism and oppression lie just below the surface of seemingly benign everyday gentility.

It’s All About Me: The Great Wall and White Savior Complex

Hello, it’s me, The Great Wall, 2017

Despite its cringeful pre-release marketing campaign I went into seeing The Great Wall with a semi-open mind. Zhang Yimou has directed some good films during his career and I was curious to see what he could do with US$150 million dollars. But right off the bat it was clear that despite being co-produced by one of the biggest production companies in China, Wanda Dalien (along with US-based Legendary Pictures), set in ancient China, and featuring a boatload of Chinese movie stars, this was going to be all about the white dude. Though I shouldn’t be surprised, I am a bit fatigued by the continuation of the white savior trope, wherein white guys rescue the benighted yellow people once again.

The film starts with a trio of European mercenaries fleeing across the Gobi desert, including Matt Damon as a character named William who speaks with a slight Irish accent, another guy who is Spanish, played by Chilean American actor Pedro Pascal, and a third guy who dies pretty quickly. Right away we know it’s going to focus on the surviving European dudes because Hollywood, and sure enough the story is told almost completely from their point of view.

Please give us more lines and a character arc, The Great Wall, 2017

The movie is seductive because it is so slick and beautifully packaged and is palatable and easy to watch. It’s seemingly respectful of Chinese culture—there are no evil Asiatic villains and several of the Chinese characters are noble and heroic, if incredibly clichéd. The film presents Chinese culture as refined and aesthetic, which is clearly meant to appeal to PRC audiences. But the narrative exists only to center the white heterosexual male perspective, so it’s no surprise that the screenplay is of course written by a white dude. Although it may seem like there are a whole lot of Chinese people in the movie they in fact are mostly window dressing who exist mainly as props for the white protags. The film actually posits that there are no archers in the entire elite Chinese regiment that’s been training for sixty years who are as good as the white dude. There’s also the highly questionable plot point that China didn’t have any magnets in their possession until white people brought them. This is especially insulting considering that the Chinese were the first to document the use of magnets and magnetism around 1088 AD. I mean, wtf?

Guilt sop, The Great Wall, 2017

The premise that a woman could be a general in ancient China is also a male fantasy of inclusion and equality that conveniently ignores the historic patriarchy and paternalism inside and outside of China that would have made this impossible. Mulan is a believable legend because it acknowledges that a woman could only be accepted in battle if she dressed like a man.The Great Wall presents females as accepted in the military hierarchy, even to the point of one of them becoming the supreme leader of the troops. While I’m all for strong female characters, the erasure of the historical oppression of women denies the suffering women have experienced in the patriarchy. Ultimately, General Lin, the female commander in The Great Wall, is a guilt sop that pretends a history of fairness and equality that didn’t exist. I suppose I should be grateful that the chaste and muted attraction between William and Lin is unconsummated or I would have run screaming from the theater.

Savioring, The Great Wall, 2017

Everything in the film is an excuse to get Matt Damon more screen time and it’s especially frustrating to see some of the biggest stars in China in what amounts to extended cameos. If you blink you would miss Lin Genxing, Lu Han, Eddie Peng, Zhang Hanyu, and more. In fact, seeing how ferocious Eddie Peng is in his three minutes onscreen made yearn for him, not Matt Damon, to be the protagonist of the film. Andy Lau and Jing Tian are the only Chinese actors with more than a handful of lines in the film and only the hot Asian babe in the shiny breastplate gets to have any notable character development.

Even the scary monsters that provide the main threat in the narrative are only partially baked, looking like a cross between orcs, dinosaurs, and the nasty creature from Alien. All in all, the movie is a confused mess of that fails to resolve in any satisfying way.The Great Wall is another fail from Hollywood (with an assist from Wanda Dalien, which has been trying to break into the US market for a while). Thank god CAAMfest is coming up next month to give us some movies about real Asian/Americans from our perspective, instead of the usual white-dude-centric nonsense perpetuated by this film.

UPDATE: Looks like THE GREAT WALL tanked at the box office in the US, and may also be taking down the entire US-China coproduction industry with it. Can’t say that I’m sorry. In fact I’m very not sorry at all.

Shall We Talk: Coming Home and Office movie reviews

In an interesting coincidence, two famous Chinese-language film directors have films opening in the U.S. this weekend, but their respective movies might puzzle the casual viewer expecting a certain type of cinematic output from each director. But on closer inspection both movies are in some ways throwbacks to early periods of each director’s filmmaking careers.

Starting with Hero (2002) and continuing through House of Flying Daggers (2002), Curse of the Golden Flower (2006), and The Flowers Of War (2011), Zhang Yimou for the most part in the 21st century made a series of glossy commercial films that have been successful marketed in the West, and he capped off this run of box-office hits by overseeing the much-lauded opening ceremony for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. So viewers who only started following Zhang’s career in the 21st century might think that his oeuvre is all about wire-fu, movie stars, a hypersaturated color palette, and an affinity for spectacle. But Zhang started out in the 1980s as one of the so-called Fifth Generation of Chinese directors who were noted for their realistic styles and politically astute commentary. Often depicting the ordinary lives of peasants in China’s rural countryside and usually starring Gong Li, Zhang’s first several features were poetic ruminations on the effects on everyday people of various types of systematic repression. These movies, including Ju Dou, Red Sorghum, Raise the Red Lantern, and The Story of Qiu Ju, made Zhang the darling of the arthouse film festival set, so it was a bit of a surprise when he busted out with a string of martial-arts fantasies at the turn of the 21st century. But those later films were pretty big at the box office and thus many folks only know Zhang as a director of big-budget spectacles, so it might seem like a surprise that Zhang’s latest film, Coming Home, includes neither martial arts nor brightly colored costumes and sets. Astute observers, however, will realize that the movie actually harkens back to Zhang’s earlier Fifth Generation output from the 1980s and 90s.

Coming Home is a family drama set during and just after the Cultural Revolution in China and is based on the novel The Criminal Lu Yanshi by popular Chinese author Yan Geling (whose novella 13 Flowers of Nanjing was the basis of Zhang’s recent film The Flowers of War). The movie opens as former professor Lu Yanshi (Chen Daoming) surreptitiously arrives back at his town after escaping from a re-education camp. His devoted wife Feng Wanyu (Gong Li) attempts to meet him but is thwarted by the Chinese secret police and Lu is sent back to prison. Lu and Feng’s teenage daughter Dandan (Zhang Huiwen), an aspiring ballerina, resents her dad’s outlaw status since it’s messing with her career plans to play the lead soldier/dancer in the school play, which Zhang drolly depicts as leftist musical featuring dancers en pointe who are wielding rifles in the service of the revolution. Cut to several years later, after the end of the Cultural Revolution in the mid-70s. Lu again returns home but Feng has become addled from either a blow to the head, PTSD, early-onset Alzheimer’s, or a combination of all three, and thus doesn’t recognize him. The film then follows Lu’s attempts to reconcile with the amnesiac Feng.

Coming Home’s muted mis en scene at first seems a million miles away from the brightly colored, glossy sheen of Zhang’s martial arts movies but the film’s meticulous art direction, featuring scuffed walls, dull brick and wooden buildings, and threadbare wool coats and trousers, reflects Zhang’s careful attention to period detail and authenticity. The usually glamorous Gong Li tones down her customary high-wattage gorgeousness to play the dowdy teacher Feng, but in her performance she seems to have acting awards in mind, as she weeps piteously over Lu’s absence, then affects a glassy-eyed dolor to simulate mental confusion. (In fact, Gong was nominated for the first time for Best Actress for Taiwan’s 2014 Golden Horse award but lost out to Chen Shiang-chyi. In glorious diva fashion Gong subsequently pitched a fit, calling the Golden Horse unprofessional and vowing never to attend again.)

Although Gong is a bit off, Chen Daoming right on the money as the long-suffering Lu. His world-weary eyes and sorrowful demeanor speak volumes about Lu’s personal traumas and his experience becomes a metaphor for the human cost of China’s various social and political upheavals. Through Chen’s sensitive and understated performance the film becomes an allegory about the erasure of memory and the amnesia of the Cultural Revolution. In this way the movie hearkens back to director Zhang’s earlier films that focused on political and cultural critique, which preceded his more recent, more commercial output. Zhang also recently released another film set during the Cultural Revolution, Under The Hawthorne Tree, but his next project is the blockbuster Andy Lau-Matt Damon China/US-coproduction action fantasy The Great Wall. So he’s nothing if not versatile—

Also releasing in North America this weekend is the latest from Johnnie To, Office. Like Zhang’s movie, Office at first may seem like an anomaly in its director’s catalog but in fact the film, which is a musical comedy, has a lot in common with To’s past work. Though To is best known in the West for hardboiled crime movies like The Mission, Election, Exiled, and his last film, Drug War, he’s got a much more varied back-catalog than that. To got his start directing at Hong Kong’s television studio TVB and there he directed everything from romances to comedies to martial arts historicals, including the famous period drama The Yang Family Saga. His prolific filmmaking output includes the fantasy action films The Heroic Trio and The Executioners, the comedy farces The Eighth Happiness and The Fun, The Luck, The Tycoon, and Stephen Chow vehicles Justice, My Foot and The Mad Monk. Although his crime films have won him much love among Asian film fanpeople, To’s most commercially successful movies have been romcoms such as Needing You and Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart 1 & 2.

So it’s not as far-fetched as it might initially seem to be that Office is a musical, with all of its leads (except Chow Yun-Fat) singing at least one song in the film. The movie is a typical workplace drama infused with cogent commentary about the crisis of capitalism, The storyline follows two young acolytes at their first days on the job at Jones & Sun, a seemingly innocuous Hong Kong cosmetics company that’s actually in the throes of backstabbing and backroom deals. President Ho (Chow Yun-Fat) has a wife in a coma and Chinese investors knocking at his company’s door, while CEO Cheung Wai (Sylvia Chang) struggles to keep the company’s profits up and its products relevant. Salesman Wong Dawai (Eason Chan) is climbing the corporate ladder and is not averse to using personal relationships, including ones with CEO Cheung as well as fellow office drone Sophie (Tang Wei), in order to advance. Youngsters Kat (Tien Hsin) and Lee Xiang (Wang Ziyi) round out the ensemble.

But despite a stellar cast who admirably perform both acting and singing duties (with Cantopop superstar Eason Chan being the best and Tang Wei the worst among the vocalists), the real star of the show is the astounding art direction and set design by acclaimed veteran William Chang Suk Ping, who has won renown as the production and/or costume designer for innumerable classic Hong Kong films including In The Mood For Love, The Grandmaster, and Dragon Inn. Office was shot completely on a soundstage, with some outdoor scenes simulated via green screen, and Chang’s beautiful, stylized set dictates the mood of the film. Comprised mostly of brightly colored bars and rails, the set resembles a massive, skeletal architectural cage that encloses the action and the characters and lends a hermetically sealed, slightly claustrophobic feel to the film. The artificial staginess of the movie, with its simulated spaces and multiple levels of activity, recalls a Broadway musical more than a movie musical, with the set dominated by a huge, slowly revolving clockface. No pretense of realism is made in the film’s use of space, color, and structural elements, which adds to the knowing fakery of the movie’s design.

Despite To being the titular director, the film displays the strong influence of Sylvia Chang, who wrote and produced the film as well as playing the lead as CEO Cheung Wai, and who has an impressive resume as the director of films such as Tempting Heart (1999), 20 30 40 (2004), and Murmurs of the Heart (2014). Chang’s hand is clearly evident in the narrative’s complex personal relationships and its focus on the collateral damage of corporate machinations. To’s romcom background also comes the fore as the movie’s love hexangle recalls the similarly structured romantic entanglement in his 2014 movie Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart 2.

The weakest element of the movie’s musical conceit is its curious lack of interesting choreography. Despite taking place on a boldly designed stage set that cries out for equally bold movement through and across it, the movement during the musical numbers is surprisingly limited. The action during the songs in Office consists of mostly of synchronized head nods and a few characters walking in rhythm together. Office could stand to take a few lessons from Bollywood musicals, whose song and dance numbers fill every inch of the frame with dynamic, kinetic movement.

But all in all, the movie is a fascinating beast that promises to be brilliant up on the big screen. After first seeing in via online screener with tiny white subtitles I’m looking forward to watching it again in a movie theater where it belongs, and so should everyone, in my humble opinion.

dir. Zhang Yimou

opens Fri. Sept. 18

dir. Johnnie To

opens Fri. Sept, 18, 2015

Recent Comments