Together Again: Triumph In The Skies and the Rebranding of Francis Ng

The day-and-date release in the U.S. of the movie version Triumph In The Skies (more popularly known as TITS) represents a renaissance of sorts for my boy Francis Ng, who’s enjoying a resurgence of popularity after a bunch of down years. Although probably best known for his straight-up thuggin’ in classic HK gangster movies like Young & Dangerous, The Mission, Exiled, and many many more, Francis has in the past year or so managed to reinvent himself and his public persona as a romantic lead, a family man, and an overall good guy. Ironically, although Francis is mostly a movie king, his rebranding has been based mostly on the popularity of a couple recent television series.

The sequel to the Hong Kong drama on which TITS is based started Francis on his road to recovery back in 2013 as TITS 2 racked up the ratings and online views in both HK and China. Francis reprised his role as Sam Gor, the serious and intense pilot for the fictional HK airline Skylette who moons over his dead wife and hooks up with the young hottie Holiday Ho. As with the original TITS back in 2004, HK audiences (as well as a sizable number of watchers in China) lapped it up and Francis’ popularity, which had mightily declined for a number of reasons (crappy film selection, aging, orneriness, and overall poor career choices) started to rise again.

But what really got things going again for Francis was another television series, the Hunan TV reality show Dad, Where Are We Going 2? which aired in 2014 and in which Francis starred with his darling boy Feynman, then five years old. The show features six celebrity dads and their ultra-cute offspring wandering the hinterlands of China and interacting with their country cousins. Due in large part to the otherwordly twee charm of his kid and his strict but loving interactions with said child, Francis made a big impression as a warm-hearted patriarch and counteracted his past rep as both a movie villain and a pain-in-the-ass diva actor. Francis released a film while the show was airing, The House That Never Dies, which was a huge box-office success in China due in no small part to his popularity on DWAWG.

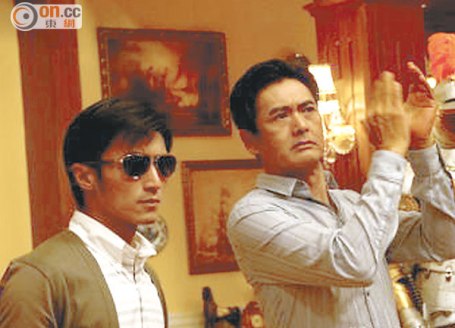

Because of the popularity of TITS2, TVB, in association with Shaw Brothers, MediaAsia and its China-based subgroup China Film Media Asia, and a couple other China-based entities, have thus teamed up to produce a film version of the iconic drama series about Hong Kong flight crews and their various romantic entanglements. But despite bringing back Francis as Sam Gor, as well as Julian Cheung Chilam as Jayden “Captain Cool” Ku, the film doesn’t manage to recreate the melodramatic success of the original 2004 series or its 2013 sequel.

To start with, the movie drops the viewer in medias res, which is fine if you know the backstories of the various characters, but is utterly frustrating for those unschooled in the minutiae of the characters or their past television lives. Weirdly enough, while relying on the audience’s assumed knowledge of the show, the movie also eliminates a lot of key narrative elements from the series, including the crucial love triangle between Sam, Jayden, and Holiday (who is gone completely missing in the movie), and in the film Sam and Jayden don’t even appear together. The film’s story consists of three vignettes featuring Sam, Jayden, and newcomer Branson (played by the inexpressive Louis Koo) which don’t interlock in any meaningful way. Aside from one scene, none of the male leads interact with each other, and Jayden seems to be on another continent for the entire film. Each of the vignettes lack any kind of dramatic tension, with almost nothing at stake for the characters, and they resolve in the most predictable ways possible. The film as a whole is missing self-awereness, irony, wit, or anything that might add a bit of an edge to the film, and the three narratives play out like long-form wristwatch adverts, with gratuitous product placements of bottled water, designer chocolates, and jd.com, the Chinese shopping site that miraculously ships within hours from Asia to London.

The lead actors don’t look too bad for their age (with Francis in his fifties and Chilam and Louis both mid-forties), and Charmaine Sheh and Sammi Cheng as the love interests are feasible and not too mismatched. Amber Kuo as Jayden’s girl-toy appears to be way too young for him, though, and their vignette in particular is pretty cringeful, relying on a remarkably tired plot twist and saddling poor Chilam with horribly clichéd romcom dialog about hearts living in other people’s bodies and the like. Sammi Cheng as a pop star (what?) is cool with her tattooed knuckles and hard-part eyebrow and she and Francis make a pretty pair, but the impetus for their hook-up is completely contrived. As a fangirl I did enjoy the sight of Sam Gor practicing his dance moves, but the question still remains: WHAT HAPPENED TO HIS FORMER GIRLFRIEND? There is also a gratuitous subplot involving a pair of mainland Chinese characters that concludes in the cheesiest way possible and which seems tacked on just so the PRC audience can hear a bit of Putonghua (inexplicably, the actor playing Louis Koo’s father also speaks Mandarin, though Louis Koo’s dialog is strictly in Hong Kong Cantonese).

As usual Francis does his thing, acting with his mouth full of food and with his eyebrows quirked, but honestly he doesn’t have a whole lot to do. There’s also a tiny bit of TITS fan service with Kenneth Ma and Elena Kong reprising their characters from the television drama and Kenneth Ma is anonymously humorous in the twenty seconds that he’s onscreen, but their appearances only underscore the calculated genesis of the film, in which the producers are trying to suck in as many customers as possible.

The entire viewing experience is like injesting an extra-large serving of Kraft Cheese Food Sticks, with lens flare, rainbows, designer clothes, and saturated color correction making for a pleasant but ultimately vacuous optical experience. Coming from a straight-up fanperson like myself who really wanted to like this movie, I think that, for all of its interminable schmaltziness, the TVB drama is actually a better product, since at least it had some interesting character conflicts and gave its performers space to emote a bit. The movie version is all hat and no cattle, with beautiful sunsets and ferris wheels and not much else. But the movie was number one at the box office in Hong Kong during the Lunar New Year holiday and made more than 100RMB during the same time period in China, which bodes well for Francis Ng and his rebooted career. He’s currently working on a film with Zhou Xun, he recently wrapped another Chinese romcom, Love Without Distance (directed by Hong Konger Aubrey Lam), and there’s already talk of another film sequel to TITS (noooooo!) Meanwhile, the Chinese film commerce machine rolls on, as TVB is planning to cash in with a movie version of another one of its recent dramas, Line Walker, with Nick Cheung and Lau Ching Wan rumored to star.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that a mainstream movie like TITS is so overtly commercial, but being an optimist I always hope that these undertakings might squeeze in a bit of craft and care and maybe even some genuine artistry. No such luck here, but kudos to Francis Ng for riding the wave and coming out on top once again.

The Glamorous Life: Human Capital film review

So there was a brief frisson of recognition amongst my film and art pals this morning to the video of Swedish director Ruben Östlund reacting to the news that his film Force Majeure hadn’t been nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Though it was pretty cheeky of Östlund to assume his film was a shoo-in, a lot of us artist types could totally relate to his mild freakout in a New York City hotel room (“Don’t undress!” pleaded his companion) as he faced this unexpected diss. Since constant rejections are part of the film/art world game, I definitely had a sympathy flinch or two when I watched the clip on my newsfeed. Östlund has since said that his reaction was sincere, (though some observers think he was pranking, especially since the video showed up on his production company’s youtube channel), but whether or not his mancrying was staged or spontaneous, it wasn’t too far from how I’ve felt many a time in the past. Of course, only five films from around the world get nominated and most do not, so Östlund is in plenty good company.

Another great movie that didn’t get nominated for the Oscar is Human Capital, Italy’s entry into the foreign-language sweepstakes. Opening this weekend, the movie is a cleverly structured look at class, privilege, greed, and desire in contemporary Italian society. The film opens with a quick sequence of events in which a bicyclist is hit by a car on a lonely country road, with the car’s driver continuing on without stopping. The movie then flashes back six months to deconstruct the events leading up to the hit-and-run from the various points of view of several key players including Dino, a scruffy social climber who mortgages his house to buy into a shady hedge fund, Carla, the anxious wife of said hedge fund’s unctuous manager Giovanni, and Serena, Dino’s teenage daughter who is involved with Carla and Giovanni’s spoiled son Massimiliano. Along the way the film touches on the social and economic divides within Italian society and the price that some people are willing to pay in order to advance themselves.

The film is sleek and fast-moving, efficiently weaving together the disparate versions of the story into a satisfying whole. Director Paolo Virzi has a sharp eye for social foibles and finds a lot of bone-dry humor in the characters’ dire situation. One amusing scene in which a group of catty drama aficionados critique the state of contemporary theater arts demonstrates Virzi’s knack for quickly and clearly delineating character traits and interpersonal tensions. He also elicits uniformly solid performances from his cast, lead by newcomer Matilde Gioli’s levelheaded turn as Serena—also good are veteran actors Fabrizio Bentivoglio as the cluelessly ambitious Dino and Valeria Bruni Tedeschi as the mournful, jittery Carla. Though based on a novel originally set in Connecticut, the story makes an effective transition to the suburbs of Milan, with Giovanni’s luxe marble villa, complete with indoor swimming pool and private tennis courts, contrasting with the Dino’s messy middle-class abode.

Director Virzi uses the multiple-point-of-view narrative technique, popularized in Kurosawa’s Rashoman back in the 1950s, to underscore the vast chasm between the stratified social classes in contemporary Italy. All of the characters believe in the veracity and reliability of their perspectives and for the most part can’t see beyond their own noses, suggesting a lack of empathy that contributes to social anomie. The exception to this is Serena, whose great sympathy for the plight of others makes her the moral center of the film. Virzi privileges her perspective by concluding the film’s fractured narrative structure with Serena’s point of view, which adds a small spark of hope that humanity might still rise up from the depravity, greed, and selfishness embodied by the other characters in the film.

A quick tip: this week is the start of the 13th Noir City Film Festival at the glorious Castro Theater in San Francisco. The ten-day festival is chock full of treats, many projected from 35mm prints. Favorite noir actors including Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Ryan, and directors Fritz Lang, Douglas Sirk, and Robert Siodmak, among many others, have films in the program, which is always a great time. Don’t miss it—I certainly won’t.

Human Capital

Opens January 14,

Landmark Opera Plaza, San Francisco

California Film Institute, San Rafael

January 14-24, 2015

Castro Theater

San Francisco

Lost In Love: Back In Time movie review

Classic Chinese pop music, known as Cantopop or Mandopop depending on the dialect, is a bit of an acquired taste. It’s all smooth edges and soft sounds, designed to soothe and comfort, as opposed to, say, the techno-hip hop flavors of Kpop. It’s no surprise that Western imports like Air Supply, kings of the power ballad, are hugely popular in China and Hong Kong. There are of course exceptions to this, including the hard-rocking Cantopop kings Beyond, but the top of the charts in Hong Kong as well as on the mainland have since the 1980s been dominated by sleek pop balladeers such as Jacky Cheung, Faye Wong, and Andy Lau.

The cinematic equivalent of Canto/Mandopop would be Back In Time, (aka Fleet of Time), which recently played here in the U.S. as a day and date release with China. The film was number one at the box office in China before being bumped off the top spot by Jiang Wen’s Gone With The Bullets. Like a lot of Chinese pop music, Back In Time is competently crafted and pleasant to experience, but soft and cloying, without a lot of rough edges.

A slick weepy with attractive leads in Eddie Peng (most recently seen kicking ass in The Rise of the Legend and Unbeaten, among other manly roles) and Nini (chief flower in Zhang Yimou’s Flowers of War), Back In Time is unabashedly nostalgic as it traces the relationships of a group of friends from their high school days to adulthood. The main narrative follows the reminiscences of businessman Chen Xun (Peng) as he recalls his chaste adolescent romance with the Fang Hui (Nini), a transfer student to his secondary school. Although the two promise everlasting devotion, for the sake of narrative tension their romance hits the skids. Will they kiss and make up or will they forever be lost to one another? The film’s gauzy, soft-focus shots of billowing curtains, rain-slicked streets, snowy landscapes, and characters literally crying in their beer heighten the overall sentimentality of the proceedings.

The movie is also fairly apolitical, despite spanning a period of great change in Chinese history (roughly 1999 to the present day). Although China went through a lot during that time, almost none of this is present in the film (except a reference to Beijing’s winning bid to be the site of the 2008 Olympics). Instead the film focuses on its youthful love story, which strips the narrative of most of its historical context and content. Compared to Taiwan’s similarly structured Girlfriend/Boyfriend (2012), which actively incorporated student political demonstrations into its story, Back In Time only briefly touches on events that occurred during its timeline. The rest of the film takes place in a historical vacuum, with the passage of time primarily reflected in the changing hairstyles and cell phones of the protagonists (with wigs worn with varying degrees of success, including Eddie Peng’s ill-fitting late-90s mop and Nini’s curiously changing hair lengths).

Lead by the pretty leading pair played by Peng and Nini, the film’s cast is winning and earnest, though in the earlier parts of the movie some of the performers look way too old to be high school students. There are also a few confusing plot developments such as a hissy fit at an outdoor restaurant that escalates without explanation into a knock-down brawl, but none of them as contrived or annoying as those found in the Nicholas Tse/Gao Yuan Yuan romantic drama stinker, But Always. But Back In Time, though by no means racy, also deals fairly frankly with sexuality, a change from many similar melodramas of its ilk that’s worth a few points in my book. At times the overwrought emotionality of the movie just barely avoids self-parody and isn’t helped by the swelling violins and tinkly piano on the soundtrack. But it’s a watchable timepass, especially if you’re in the mood for a deeply emo cinematic experience.

With Back In Time, distributor China Lion continues to hit its stride. Unlike the typical Asian genre fare of gangster, martial arts, and wuxia films usually distributed in the U.S. and aimed at Western sensibilities, CL’s most recent releases aim straight for the Chinese expat community. Its last five titles released in 2014—Back In Time, Women Who Flirt, Love On A Cloud, Breakup Buddies, and But Always—are romantic dramas or comedies and feature performers popular in China but mostly unknown in the U.S. even among Asian film aficionados, with the exception of Nicholas Tse and possibly Zhou Xun. These movies also differ from the output of international arthouse favorites like Zhang Yimou or Chen Kaige and are solidly middlebrow and commercial, created to entertain and not to startle, and have found an audience in the U.S. Deadline.com notes, “China Lion has had success with romantic dramas imported from Chinese-speaking regions in the past. They handled Beijing Love Story ($428K cume) in February and other past titles include Love ($309K cume) and Love In The Buff ($256K cume).”

Back In Time (as well as the CL releases that immediately preceded and follow it, Pang Ho-Cheung’s Women Who Flirt and the Angelababy vehicle Love On A Cloud) demonstrates that China Lion has figured out a winning formula that works for its Chinese expat niche audience. Though many of these films may not be appealing to the typical Asian-film fanboy in the U.S., to Chinese audiences away from home they’re just like listening to the latest Jacky Cheung CD—they’re a soothingly familiar entertainment experience.

Tiger By The Tail: The Taking of Tiger Mountain movie review

Legendary director Tsui Hark has been a fixture on the Hong Kong cinema scene since the 1970s (except for a little hiccup in the 90s when he made a couple crappy Hollywood movies with Jean Claude Van Damme, but let’s not talk about that now). His string of significant cinema work started in 1979 with The Butterfly Murders, moved through the 1990s with a slew of indispensible films including A Better Tomorrow (producer), A Chinese Ghost Story (producer), and the Once Upon A Time In China series (director), and continues to the present day with a clutch of period action films including Detective Dee 1 & 2 and Flying Swords of Dragon Gate. His latest joint, The Taking of Tiger Mountain, just opened in the U.S. a week after its successful debut in China, where it’s the top film at the box office.

The film is based on a popular Beijing opera (from the novel Tracks in the Snowy Forest) that was one the Eight Model Plays sanctioned by Mao during the Cultural Revolution. The opera was adapted into a film in 1970 that Tsui Hark, along with most of China’s other 800 million people at the time, viewed as a youth. Tsui’s current adaptation is a co-production of the heavy-hitting commercial studio BONA Film Group and the August First Film Studio, which is the film-producing branch of China’s People’s Liberation Army, and the influence of these disparate financing sources shows in the finished product. While it mostly passes as an energetic action/adventure movie, Tiger Mountain also has the smell of Chinese military propaganda, which inhibits some of director Tsui’s more maverick instincts.

The story is based on a true incident that took place in 1946 during China’s civil war, in which a small platoon of PLA fighters overcame a much larger bandit crew (alluded to as affiliated with the Kuomintang, the PLA’s opposition during the civil war) that’s holed up in a mountain stronghold. The film opens with a framing device in which Jimmy (Han Geng), a young modern-day Chinese student in the U.S., sees a snippet of the 1970 Taking Tiger Mountain film. As his buddies laugh at the old-fashioned opera stylings, Jimmy smiles fondly and later watches the film on his phone as he travels home to Harbin. The movie then cuts to the main action as the PLA platoon struggles to protect a village from the KMT bandits while confronting a lack of food and supplies as well as the onset of winter. As the situation worsens the platoon’s leader, known only as 203, decides to storm the bandit’s hideout on Tiger Mountain, sending in Yang (Zhang Hanyu), a PLA intelligence agent, to infiltrate the gang. The main body of the film follows Yang as he works from within the bandits’ lair while his compatriots endeavor to attack the stronghold from without. After a somewhat slow setup the narrative picks up speed around the forty-minute mark once Yang makes his way into the good graces of the bandit leader, Hawk. Following much intrigue and double-crossing the film concludes with a rip-roaring battle in the snowy mountain as the heroic PLA troops clash with the diabolical KMT bandits.

Tiger Mountain was released in China in 3-D (although its U.S. release is only in 2-D), and the film’s first brief battle sequence feels a bit too gamish, with slo-mo bullet-cam shots and computer-animated blood spurts probably better appreciated stereoscopically, The later, more extended action sequences, including an outstanding siege of a small village, are more engaging and rely less on CGI and more on real hand-to-hand combat and kinetic fight choreography. The climatic battle sequence and a brief coda involving a runaway plane are both pretty thrilling and demonstrate Tsui’s sure hand with action, characters, and special effects.

Tsui draws out solid performances throughout, although some of the film’s characters fall into standard war-movie types. Zhang Hanyu is dashing and resourceful as Yang, the fearless PLA spy sent to infiltrate the bandit camp, and he has several outstanding moments that convincingly demonstrate Yang’s ability to think on his feet. Tony Leung Ka-Fai plays a few years older in a bald-wig and hook nose as Hawk, the ruthless bandit leader, and it’s great to see him sink his teeth into the meaty character role. Lin Genxing is forthright, square-jawed, and handsome as the platoon’s captain but otherwise isn’t terribly compelling. Yu Nan doesn’t get to exercise her usual steely bravado since she’s mostly a captive throughout, though she does escape her bondage several times during the course of the film. Tong Liya as Little Dove, the doughty nurse, is predictably brave and lion-hearted. There’s also a cute little traumatized kid who gets to play a heroic role in the last battle as well as provide a manipulative emotional moment at the film’s climax.

As a Western viewer it’s a bit odd for me to root for the PLA since in my mind the Chinese army is forever linked with the 1989 brutality of Tiananmen Square, but PRC audiences undoubtedly have more positive associations with China’s military. Chinese viewers also probably feel a more visceral response to the strains of the familiar revolutionary opera on the soundtrack and find kinship with Jimmy and his nostalgic journey home to rediscover his family’s PLA roots.

In fact, Jimmy can be seen as a surrogate for Tsui himself, as at the outset of the film he recalls his nostalgic U.S. encounter with the original Taking Tiger Mountain film. Later, at the film’s conclusion, Jimmy is surrounded by a cadre of PLA soldiers and can only smile helplessly, submitting to the collective PLA memories, even as he tries to re-imagine a different version of the narrative’s conclusion. The PLA perspective, and by extension the August First version of the story, is too overwhelming to contradict.

Under different circumstances Tsui really could’ve cut loose but may have felt constrained by the sanctity of the material and/or by the military film office breathing down his neck. The film is much less irreverent and less of a pointed critique than some of his earlier productions that scathingly sent up organized religion (Green Snake), corrupt government officials (New Dragon Gate Inn), and colonial malfeasance (Once Upon A Time In China). Nonetheless, hints of Tsui’s signature style sneak in via the Road Warrior-esque bandit fashions including mohawks, facial tats, and various other quirky costuming choices that recall the art direction of Tsui’s earlier films including The Blade. Another glimpse of the film that might have been is an electrifying throwaway coda involving a speeding fighter jet, a long tunnel, and a very high precipice. Still, The Taking of Tiger Mountain is nowhere near as heinously patriotic as earlier glossy August First propaganda productions like The Founding of A Republic from a few years back. It’s to Tsui’s credit that he’s able to create a highly watchable and sometimes exhilarating film, however restricted he may have been by his material and his funding sources.

The Ferguson Masterpost: How To Argue Eloquently & Back Yourself Up With Facts

I’m in Asia right now so I’m viewing the Ferguson grand jury verdict aftermath from afar, but this article is an outstanding resource for talking about all the issues around it. I can’t add too much more to it since it’s thorough and comprehensive.

In The Still of the Night: Hong Kong Cinema film series

2014 was a pretty good year for Hong Kong movies and this year’s Hong Kong Cinema, the San Francisco Film Society’s annual film series from the former crown colony, reflects this uptick in cinematic quality. Recent output from brilliant directors Ann Hui, Pang Ho-Cheung and Fruit Chan are part of the mix, superstars Chow Yun-Fat, Tang Wei, Nicholas Tse, and Louis Koo (twice) are featured players, and the films run the gamut from crime thriller (Overheard 3) to youth romance (Uncertain Relationships Society) to wuxia pian (The White Haired Witch of Lunar Kingdom) and beyond. The series also includes a twentieth-anniversary screening of Wong Kar-Wai’s glorious slice of Hong Kong-meets-the-Nouvelle Vague, Chungking Express, which is definitely worth a watch on the big screen. A few other highlights follow.

From Vegas To Macau (dir. Wong Jing) is a cheesy quasi-sequel to Hong Kong’s many, many successful gambling comedy movies from the 1980s and 90s. Although luminaries including Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Andy Lau Tak-wah made their mark in gambling epics from that time, one of the pillars of the genre is God of Gamblers (1989), starring Chow Yun-Fat and directed by Wong Jing. In From Vegas To Macau Chow and Wong reunite in an attempt to resurrect their glory days, and by extension the glory days of Hong Kong movies, and the current film is a reminder of the best and worst of those times. In the plus column is Chow cutting loose in a wacky Hong Kong comedy, which helps to counter his mostly disappointing 10-plus years sojourn to Hollywood and which enables him to regain his crown as the Chinese god of actors. Appearing in the sidekick role, Nicholas Tse is an earnest straight man, and Chapman To overacts mightily to insure that Cantonese-language cinema’s laff-riot slapstick tradition continues.

For anyone who’s only familiar with Chow Yun-Fat’s iconic work as a soulful gangster in John Woo movies (and who haven’t seen him as a childlike amnesiac in the original God of Gamblers), this zany farce should be an eye-opener, as Chow turns on the high-pitched giggle and the crazy dance moves as a Ken, the godly gambler/con man at the center of the film. Watching a Wong Jing movie is kind of like blindly sticking your hand into a big mysterious barrel—you never know what random trash you’re going to pull out, and From Vegas To Macau is no exception. Wong strings together a series of vignettes and set pieces without regard to narrative logic, each scene clashing violently with the the others, and the tone of the film swings from action to slapstick to farce, with kung fu, booby-traps, CGI-enhanced card-shuffling, and fat-chick jokes all a part of the overstuffed mix. While it’s not a good movie in any sense of the word, its manic energy and illogical construction combined with the spectacle of Chow Yun-Fat goofing his way through a typical Hong Kong comedy makes it a decent timepass.

At the other end of the cinematic spectrum is Ann Hui’s The Golden Era, starring Tang Wei (Lust, Caution) as iconographic Chinese author Xiao Hong, who worked during the Republican era in China (she was born in 1911 and died in 1942) and who was one of the first modern-day female writers in the country to gain recognition. The film is beautifully made, with a lot of money evident in the stunning cinematography, costumes, and art direction, and boasts an excellent cast, but at three hours it’s overly long and at times glacially paced. The film makes liberal use of direct address, including an opening speech by Xiao Hong herself as she announces her birth and death dates, adding a self-reflexive layer to the narrative structure. Tang Wei is thoughtful and arresting as Xiao Hong, who was born into a patrician Chinese family but subsequently lived in poverty and uncertainty for much of her short life. However, her performance lacks a sense of agency and ferocity that a more intense actor might have brought to the role. In addition, those viewers unfamiliar with Xiao Hong’s body of work might be at a loss as to her significance, although many of the supporting characters repeatedly attest to her importance in China’s literary canon. Still, it’s interesting to see what director Hui has done with a generously budgeted film set in historical mainland China, since much of her oeuvre have been in the vein of A Simple Life or The Way We Are, which are much more quickly sketched stories deeply rooted in contemporary Hong Kong. Although there are stylistic differences between those movies and this one, Hui’s filmic intelligence shines through, as she’s made a smart and intriguing picture about the intersections of history, art, politics, and creativity.

Splitting the difference between Wong Jing and Ann Hui is Pang Ho-Cheung’s Aberdeen, which is an engaging look at contemporary Hong Kong through the lens of several intertwined relationships. The film follows the lives of the members of two related families, including a thirty-something actress/model (Gigi Leung) who is transitioning from her ingénue stage to something less well-received; her husband (Louis Koo), who is concerned that their daughter isn’t as pretty as he thinks she should be; his sister (Miriam Yeung), who’s obsessed with her fraught relationship with her late mother; and her husband (Eric Tsang), a doctor who’s making time with his receptionist. Intercut with these various subplots are a beached whale, unexploded WWII ordnance in the heart of Hong Kong, fantasy sequences with larger-than-life lizards, and Taoist funeral rituals. By interweaving these disparate elements director Cheung examines notions of beauty, fame, family, and loyalty amidst the backdrop of modern-day Hong Kong. The film continues in the vein of much of Cheung’s past work exploring Hong Kong life and relationships, which range from the brilliantly satirical Vulgaria to the rom-com Love In A Puff to the dark and disturbing Isabella.

In some ways Aberdeen recalls the glory days of UFO, the United Filmmkaers Organization production house that back in the 1990s was responsible for a slew of dramedies including Dr. Mack; Heaven Can’t Wait; Tom, Dick, and Hairy; and Twenty Something. UFO movies were smarter and less formulaic than the typical commercial Hong Kong output of the time and starred early 1990s superstars like Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Tony Leung Ka-Fei, Karen Mok, Jordan Chan, and Anita Yuen, all of whom were looking for prestige projects that were a break from Kong Kong’s usual kung-fu historicals or generic crime movies. Aberdeen carries on in this tradition, which stars current A-listers Louis Koo, Miriam Yeung, Eric Tsang, and Gigi Leung, as well as appearances from Hong Kong movie vets Ng Man-tat and Carrie Ng, in a quality production by a name-brand director. For the most part, although flawed, Aberdeen is infinitely more intelligent and watchable than much recent commercial Hong Kong cinema and gives its cast members a good opportunity to stretch out and to exercise their acting chops.

Hong Kong Cinema runs from Nov. 14-17, 2014 at the Vogue Theater in San Francisco. Go here for ticketing and full schedule.

Drunk In Love: Asian Males in Hiroshima Mon Amour and The Crimson Kimono

As Asian American film scholar Celine Parreñas Shimizu notes, there is “a long tradition in Hollywood movies of iconic portrayals of Asian American men (as) rapacious and brutal, pedophiliac, criminal, treacherous and also romantic, and quaint. Sexuality and gender act as forces in the racialization of Asian American men.” Sadly, despite tiny steps towards improvement, Asian male representation in Hollywood still remains timidly entrenched in stereotypes. Sure, John Cho is the leading man in Selfie, (although he’s already starting to be a bit stalkerish), and Glenn (Steven Yeun) from The Walking Dead is still alive and human (though there are persistent rumors of his imminent demise), but on the big screen the ridiculously hot Lee Byung-Hun is still playing the bad guy (most recently in the upcoming Terminator: Genisys) instead of fulfilling all of our fantasies as a romantic lead.

Strangely enough, our modern era is in some ways more regressive than, say, 1959. Althought the 1950s weren’t known for their progressive portrayals of Asian Americans in Western films, in that year Asian men appeared as objects of desire in two significant movies. In 1959 the Hawai’ian born Sansei actor James Shigeta made his big-screen debut in Sam Fuller’s film The Crimson Kimono, playing a Los Angeles detective assigned to the case of a murder of an exotic dancer. The film is an engaging cop movie but it’s most notable for its portrayal of a love triangle involving Shigeta, his white partner Sgt. Charlie Bancroft, and Bancroft’s girlfriend Christina, who is also white. Unlike most such romantic conflicts involving an Asian man opposite a white guy, in this case Shigeta got the girl, which made The Crimson Kimono a groundbreaking anomaly in Hollywood. James Shigeta was a co-winner of the 1960 Golden Globe Award for Most Promising Male Newcomer and he would go on to a moderately successful career as a romantic lead for a few years but he never became the superstar that his good looks and charisma would indicate. Like most Asian American men in Hollywood up until and after that time Shigeta ran into the impenetrable glass ceiling of racism.

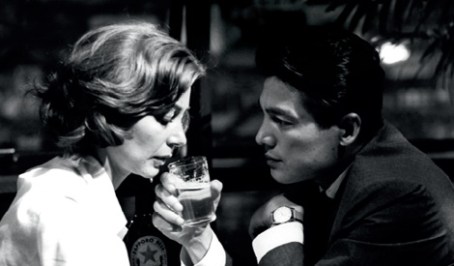

1959 also saw the depiction of another desirable Asian male, in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour. In that film Eiji Okada plays the intensely romantic Lui, a Japanese architect who has a brief and torrid affair with a Frenchwoman played by Emmanuelle Riva (seen most recently in Michael Haneke’s Amour). With a screenplay by noted Asiaphile Marguerite Duras (L’Amant/The Lover; Un barrage contre le Pacifique/The Sea Wall), Resnais’ film depicts Lui as suave, tender, and desirable, which contrasts greatly with the ways that Hollywood has typically portrayed Asian men. Okada is particularly swoonworthy as he and Riva’s character passionately discuss love, war, genocide, and beauty, against the backdrop of the site of first the atomic bomb attack. With the ruins of Genbaku Dome in the background, the film also utilizes a nonlinear narrative structure that links the European front, as exemplified by a long flashback set in France, to the Pacific theater, with Hiroshima repping for all of Japan. Set some fifteen years after the end of World War II, the film emphasizes the human cost of the war even many years after its ceasefire, as both Lui and Elle have been scarred by the loss of loved ones in the conflict. Elle fetishizes both her late German lover and Lui, as she is drawn to them due to their difference and otherness.

Now releasing theatrically for the first time in years in a new 4K digital restoration, Hiroshima Mon Amour remains fresh and relevant both thematically and stylistically (it’s regarded as one of the most influential films of the early Nouvelle Vague, or the French New Wave). It’s also an example of an early representation of an Asian male as not a caricature, a villain, or a clown, but as a fully fleshed out, highly desirable romantic lead. Now if only Hollywood could get a clue and do the same in the 21st century.

Opens October 31

3290 Sacramento St.

San Francisco CA

(415) 346-2228

Cool Like That: Who We Be book review

Jeff Chang’s latest book, Who We Be: The Colorization of America (St. Martin’s Press), dropped last week and it arrives as the United States is in the midst of another particularly fraught period of racial politics. As recent events in Ferguson, MO have indicated, Chang’s book argues that we as a country and a culture are a long way from becoming the post-racial society supposedly heralded by the election of Barack Obama, yet despite the seemingly dire straits that we’re in, all is not hopeless. In WWB Chang recounts the effects of the changing demographics in the U.S. since the mid-twentieth century, from desegregation through multiculturalism to the shooting of Trayvon Martin and beyond, investigating the ways in which visual culture intersects with current and historical events.

WWB is an amazing tome, encompassing topics as broad as the civil rights movement and as focused as Budweiser’s “Wassup” ad campaign. The book is an outstanding look at the ways in which we as a people in the United States since the mid-twentieth century have moved through a sea change of perceptions, representations, and reflections of racial relations.

Beginning in the 1960s, Chang’s book interweaves topics as diverse as the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy,” the 2001 World Trade Center attacks, the subprime mortgage scandal, Occupy Wall Street, and the psychology of advertising. Chang focuses on a range of culture creators including cartoonist Morrie Turner, whose comic strip Wee Pals featured a multiracial cast of kids, Faith Ringgold, an early advocate for the Black Arts Movement, Daniel Martinez, known for his performance art/museum tag/culture bomb from the 1993 Whitney Bienniel, and Shepard Fairey, designer of both the Andre The Giant “Obey” street art campaign and the 2008 Obama “Hope” image.

Chang does a great job exploring the ways in which real life, visual art, and commerce interact and influence each other. For instance, Chang explores a proto-multiculti Coke ad campaign from the early 70s that tried to latch onto the youth culture and nascent ethnic studies movement of the time but that didn’t mention any of the harsher realities of, say, the Watts riots. Another section of the book drills down into the racism and elitism of the 1980s and 90s New York visual arts scene, including a particularly culturally tone-deaf incident surrounding the white artist responsible for “The Nigger Drawings.” Chang closely examines this volatile period during which contemporary arts gatekeepers like the New York Times, gallery directors, and curators were forced to confront their biases against creative work by artists of color and queer artists, which reached a crescendo during the controversial 1993 Whitney Bienniel, which was vilified by the art establishment as “a theme park of the oppressed.” Chang then discusses the ways in which these so-called culture wars in turn lead to the commercialized multiracialism of the United Colors of Benetton “Colors” magazine and ad campaign.

Chang also astutely looks at what he calls “the paradox of the post-racial moment,” wherein the U.S can elect Barack Obama president, yet still has trouble reconciling Obama’s biracial identity. Chang’s analysis is particularly keen when exploring the current confused state of race relations in the U.S., describing what he calls the tendency for many people to be “colormute,” that is, to avoid talking about race for fear of being accused of racism. He ironically notes the convoluted logic behind those who frown on discussing race in any way, stating, “If bad people had used race to divide and debase . . . then good people would be polite to never acknowledge race at all. It was better not to say anything than to risk being seen as a racist.”

Chang concludes his book with two contrasting case studies–a detailed look at George Zimmerman’s murder of Trayvon Martin and the rise of the DREAM Act, the proposed federal legislation that addresses the citizenship status of undocumented young people brought to the U.S. while children. By juxtaposing these two cases Chang emphasizes the fact that, while the Martin killing demonstrates that the U.S. remains far from being a post-racial society, there is still reason for hope, as seen in the increased activism by immigrant youth of color under the DREAM Act.

Chang’s writing is clear and accessible, and his analysis is thoughtful, concise, and innovative. Though by no means a dis on the theory queens among us (and you know who you are), after recently wading through a few visual culture publications, it’s a pleasure and a relief to read an author who writes with clarity without sacrificing intelligent intellectual commentary. Who We Be is a significant and essential addition to the study of contemporary U.S. art, culture, and politics.

Jeff Chang is on a book tour to promote WWB! Find out more here.

Que Caramba Es La Vida: Mill Valley Film Festival 2014

The Mill Valley Film Festival’s 2014 edition starts this weekend and as per usual it’s a star-studded affair, with guest appearances by the likes of Hilary Swank, Jason Reitman, Billy Joe Armstrong, Ellie Fanning, Laura Dern, Metallica, and many more Hollywood glitterati. The program also boasts an outstanding lineup of documentaries, including several by local filmmakers, so the reasons for driving across the Golden Gate Bridge (or the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge, depending on your homebase) are manifold.

This year the festival is spotlighting Spanish-language cinema from around the world, including the excellent documentary Que Caramba Es La Vida, an intriguing portrait of the fierce and talented women mariachis of Mexico City. Directed by veteran German filmmaker Doris Dörrie, the movie documents the experiences of several female performers working to make a mark in a field dominated by men. The film is shot mostly verite-style with no narration, as each of the women describes how she came to be a mariachi and why she continues in the business. Some come from mariachi families, with parents or grandparents who performed before them, while others are the first in their families to perform. A particularly compelling story is that of Maria del Carmen, a mariachi singer who lives with her single mom and young daughter in a small apartment in Mexico City. Del Carmen’s mother recalls that even as a girl, her daughter Maria had a voice “that went right through you,” and this is pretty apparent after hearing del Carmen soulfully belt out a couple songs in the Plaza Garabaldi, which is home to scores of mariachi bands plying their trade every night. The film depicts del Carmen’s everyday performance prep routine, as her mom and daughter help her with her makeup and hair, as well as revealing her concerns for her daughter’s future as a female growing up working-class in Mexico. The movie also follows Las Pioneras, a group of older female mariachi groups whose members who are now in their sixties and seventies and who started out as mariachis in the 1950s as teenagers and young women. The last quarter of the movie follows the Dia de los Muertes celebrations in Mexico City, neatly contextualizing the mariachi tradition. Que Caramba Es La Vida effectively looks at some of the social and cultural milieu surrounded the women, including the effects of drug dealers, misogyny, poverty, and crime on their ability to keep performing.

Mexican music of a different sort is profiled in For Those About To Rock: The Story of Rodrigo y Gabriela. Rock journalist and first-time director Alejandro Franco narrates his very accessible portrait of the popular Mexico City guitar duo, from their roots in the capital listening to thrash and heavy metal like Megadeth, Metallica, and Slayer as teenagers. Both subjects are fluent in English and were raised in middle-class Mexican families, so their stories for the most part are very different from their mariachi counterparts in Dörrie’s film. The film is a standard biopic of a successful musical outfit so, unless you’re a big Rodrigo y Gabriela fan, the movie is less compelling than Dorrie’s movie. The film starts out strong, quickly and succinctly contextualizing the Mexico rock music scene, but bogs down in the middle as it becomes a fairly linear recounting of R&G’s career.Although the film is about musicians, one of its shortcoming is that there isn’t actually enough of R&G’s music in the earlier part of film, so if you’re unfamiliar with the duo you might not know what the fuss is all about. The film makes the mistake of telling and not showing, which weakens its impact—there are a lot of talking heads explaining things and not enough things happening instead. Whereas Que Caramba takes place on the streets and in the plazas of Mexico City, For Those About To Rock happens mostly in recording studios, backstage, and at clubs, and concerts, and is more of a fannish tribute about legend-building than an incisive look at the duo. There is also not much dramatic tension—the director refers to the story as a “fairy tale’ and it’s presented as such, with R&G destined to achieve their rock star ambitions. The viewer learns very little about either musician’s personal life or any deep, compelling reasons for why they make music other than “it’s fun”, and the film lacks a strong sense of a cultural context for who they are and where they came from. The film ends with about ten minutes of live concert footage that only underscores the relative paucity of music in the rest of the film, which may be enough of a reason for admirers of Rodrigo y Gabriela to watch the film.

The Mill Valley Film Festival eleven days beginning on Oct. 2 in various theaters in and around Mill Valley. Go here for complete schedule and ticket information.

Recent Comments