Posts filed under ‘movies’

Funeral Tango: International Film Noir at the Roxie Theater

Starting this Thursday, the Roxie plays host to A Rare Noir Is Good To Find: International Film Noir 1949-74, the followup series to last fall’s wildly popular noir showcase, The French Had A Name For It, which sold out most of its shows in its week-long run of classic French crime movies. The team behind that blockbuster event, former Roxie programmer Elliot Lavine and Midcentury Productions’ Don Malcolm, have put together another great calendar of notable noir, this time from around the world. Included in the program are fifteen films from ten different countries including France, Japan, Finland, Hong Kong, Denmark, Mexico, Greece, South Korea, Brazil, and Poland.

Screening in a triple-bill matinee on Saturday are three films from Japan that exemplify Japanese cinema’s effortless mastery of noir. Underworld Beauty (1958), by legendary director Seijin Suzuki, involves a bunch of guns, a fistful of stolen diamonds, a feisty gal named Akiko and an honorable ex-con, yakuza, double-crossing, shivs, and wild lindy hops, all presented in Suzuki’s garish and exhilarating style.

The second film of the trio, Pale Flower (1964, dir. Masahiro Shinoda), is a bleak little tale of gangsters, gambling, drugs, and a mysterious woman named Saeko who hangs out at a flower-card den and gets involved with the recently released prisoner Muraki, who’s just finished serving time for a gangland hit. Shot mostly at night and populated by junkies, yakuza, and gamblers, the film is a classic noir tale of desperation, addition, and fatalistic longing.

Rounding out the threesome is Intimidation (1960, dir. Koreyoshi Kurahara), a low-budget psychological thriller about a bank executive who gets caught with his hand in the cookie jar and who is blackmailed into larceny and crime. Clocking in at just over an hour, the film almost feels like an extended episode of Perry Mason, economically telling a tightly wound story of human corruption and greed.

The Wild Wild Rose (1960, dir. Tian-Ling Wang) features Hong Kong superstar Grace Chang, who ignites the screen as a flirty chanteuse involved in an ill-fated romance. Chang is a five-tool player, as she can sing, dance, act, and emote, and also looks like a million bucks. Chang applies her multi-octave vocal range to Mandarin-language adaptations of several songs from Carmen including a jazzy version of Habanero, as well as the aria from Madame Butterfly. She’s also surprisingly sympathetic as a bar girl who claims she can steal the heart of any man she chooses and who finds that her own heart is also at risk. The movie mixes melodrama, romance, a gangster named Cyclops, young lovers on the lam, and killer song-and-dance numbers into a heady brew.

I love American film noir but I love the idea of global noir even more, and I’m totally amped that the Roxie is presenting this brilliant series. Don’t miss it—

A Rare Noir Is Good To Find: International Film Noir 1949-74,

March 19-23, 2015

Roxie Theater

3117 16th Street

San Francisco CA 94110

415/863-1087

Nothing Compares 2 U: 2015 CAAMfest

CAAMfest, everyone’s favorite San Francisco-based Asian American arts festival, starts up this week and as usual it’s stuffed with films from Asian and Asian American directors, musical happenings, and food events. The festival spotlights veteran documentary filmmaker Arthur Dong, including a premiere of his new feature-length documentary The Killing Fields of Dr. Haing S. Ngor, which is about the Cambodian doctor perhaps best known for his Oscar-winning turn in The Killing Fields in 1984 and whose mysterious murder tragically ended his life some years later. Former CAAMfest/San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival director Chi-Hui Yang curates a program of shorts, Playtime, that includes Trails, Cyrus Tabar’s hallucinogenic microportrait of Tokyo, as well as a revival of the rarity Snipers In The Trees (1985), an early experimental short by Curtis Choy (The Fall of the I-Hotel). Below are a few other highlights of the upcoming cinematic onslaught.

Dot 2 Dot

Amos Why’s debut feature is the real deal, an intriguing look at Hong Kong’s past and present that uses the city’s unique history and geography as a backdrop for a thoughtful commentary on the transience of culture, place, and identity. The film follows Chung, a Chinese Canadian expat returning to HK who leaves dot-to-dot puzzles inscribed on the walls of the stations of the MTR, Hong Kong’s ubiquitous subway system. A recent mainland China emigre (Meng Ting-yi) begins to decipher Chung’s cryptograms and the two begin a virtual courtship, linked by Chung’s mysterious symbology. Director Why captures a street-level view of contemporary Hong Kong that’s filled with ordinary people who represent the multifaceted denizens of the city in the 21st century. The movie includes lots of non-touristy Hong Kong locations and has a great feel for the everyday sights and rhythms of the city. Hong Kong movie fans can also spot Susan Shaw as a language-school headmistress, and Tze-chung Lam, aka the chubby guy from Stephen Chow’s Shaolin Soccer, as a teacher, as well as TVB star Moses Chan (hiding his celebrity good-looks behind black-framed eyeglasses) as Chung. Though it fondly recalls the Hong Kong of the past, the movie isn’t overly sentimental or nostalgic. It’s a nice look at what’s vanished in Hong Kong over the past few decades and the rapidly accelerating changes in the city.

Hollow

This US/Vietnam co-production is a slick and creepy horror movie by Ham Tran, the director of Journey From the Fall (2006), which looked at the experiences of Vietnamese immigrants in the US, as well as last year’s glam-slam How To Fight in Six-Inch Heels. Hollow is a quite a departure from Tran’s debut film and demonstrates both the uptick in genre films directed by Asian Americans in the past few years as well as the trend toward US/Asia co-productions. The story centers on Chi, whose younger half-sister Ai apparently drowns in a nearby river, causing Chi much guilt and anguish. But when Ai later turns up a few kilometers down the river seemingly alive and well, things take a turn for the supernatural as the young girl develops a greenish pallor, scratches at mysterious wounds, and otherwise exhibits signs of demonic possession. The movie does an good job blending Viet ghost stories with modern-day horror film tropes and for the most part keeps the source of the mysterious child-possession hidden until the end. I would like to have seen a bit more agency on the part of Chi’s character but the film draws interesting parallels between sex traffickers and malevolent spirits, trying together past and present evils in Viet society. The movie is nicely shot, although the soundtrack relies a bit too heavily on sudden loud and jarring violin sounds to emphasize the scary bits in the story, but there are some nice visceral touches—it’s always rewarding to see pimps and child abductors vomiting gallons of river water.

Nuoc 2030

Nuoc 2030 is another US/Viet genre film coproduction, this one a science-fictional look at Vietnam in 2030, which is by then mostly flooded by global warming. The film’s title plays on the dual translation of “nuoc,” which means both “water” and “country” in Vietnamese. Despite a modest budget, director Nghiem-Minh Nguyen-Vo does an excellent job of world-building with his imaginative use of existing locations and evocative imagery to suggest a drowned world. The poetic narrative centers on Sao, a fisherman’s widow searching for clues to her husband’s murder in a watery Vietnam of the not-too-distant mid-21st century. For the most part the film delicately renders its futuristic storyline with imagination and vision, mixing in environmentalism, genetic engineering, and a fatalistic romance.

Flowing Stories

Jessey Tsang Tsui-Shan’s outstanding documentary looks Ho Chung village, a small settlement in Hong Kong’s New Territories, an area which is currently undergoing a construction boom due to its location near the Hong Kong/China border. Due to the harshness of farming in the region many NT residents immigrate to Europe to find work, including the two generations of the Lau Family featured in Tsang’s film. Tsuan shot much of the film during the village’s ten-year festival that occurs every decade, using that event as a means of examining the ongoing village diaspora and its effects on the residents. The Laus dispersed primarily to France and the UK and the film also includes footage of their lives overseas, with the resulting French/English-speaking children, intermarriages, and mixed-heritage offspring. Only the family’s world-weary matriarch remains in the village, where she bitterly reminisces about the poverty and hardship of farm life and her still-raging anger at her late husband, who emigrated to the UK decades before and who was only able to return a handful of times to visit his wife and children. The film is an excellent testament to the effects of globalization and the costs of modernization on ordinary people but it’s by no means downbeat or depressing, as it also celebrates the endurance of and connections to the villagers’ cultural roots as they return every decade to celebrate the festival.

My Voice, My Life

Oscar-winner (and former San Franciscan) Ruby Lam’s latest film follows several at-risk Hong Kong high school students as they prepare for a large-scale musical production. This verite-style doc celebrates the struggles and accomplishments of those who have been left out of Hong Kong’s fast-lane, including students from a school for the blind, recent mainland China immigrants, and those whose academics keep them from top-ranked educations. Part Fame, part Frederick Wiseman’s High School, the movie subtly reveals a lot about the social strata of contemporary Hong Kong and its constantly changing cultural milieu.

March 12-22, 2015

San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley

Together Again: Triumph In The Skies and the Rebranding of Francis Ng

The day-and-date release in the U.S. of the movie version Triumph In The Skies (more popularly known as TITS) represents a renaissance of sorts for my boy Francis Ng, who’s enjoying a resurgence of popularity after a bunch of down years. Although probably best known for his straight-up thuggin’ in classic HK gangster movies like Young & Dangerous, The Mission, Exiled, and many many more, Francis has in the past year or so managed to reinvent himself and his public persona as a romantic lead, a family man, and an overall good guy. Ironically, although Francis is mostly a movie king, his rebranding has been based mostly on the popularity of a couple recent television series.

The sequel to the Hong Kong drama on which TITS is based started Francis on his road to recovery back in 2013 as TITS 2 racked up the ratings and online views in both HK and China. Francis reprised his role as Sam Gor, the serious and intense pilot for the fictional HK airline Skylette who moons over his dead wife and hooks up with the young hottie Holiday Ho. As with the original TITS back in 2004, HK audiences (as well as a sizable number of watchers in China) lapped it up and Francis’ popularity, which had mightily declined for a number of reasons (crappy film selection, aging, orneriness, and overall poor career choices) started to rise again.

But what really got things going again for Francis was another television series, the Hunan TV reality show Dad, Where Are We Going 2? which aired in 2014 and in which Francis starred with his darling boy Feynman, then five years old. The show features six celebrity dads and their ultra-cute offspring wandering the hinterlands of China and interacting with their country cousins. Due in large part to the otherwordly twee charm of his kid and his strict but loving interactions with said child, Francis made a big impression as a warm-hearted patriarch and counteracted his past rep as both a movie villain and a pain-in-the-ass diva actor. Francis released a film while the show was airing, The House That Never Dies, which was a huge box-office success in China due in no small part to his popularity on DWAWG.

Because of the popularity of TITS2, TVB, in association with Shaw Brothers, MediaAsia and its China-based subgroup China Film Media Asia, and a couple other China-based entities, have thus teamed up to produce a film version of the iconic drama series about Hong Kong flight crews and their various romantic entanglements. But despite bringing back Francis as Sam Gor, as well as Julian Cheung Chilam as Jayden “Captain Cool” Ku, the film doesn’t manage to recreate the melodramatic success of the original 2004 series or its 2013 sequel.

To start with, the movie drops the viewer in medias res, which is fine if you know the backstories of the various characters, but is utterly frustrating for those unschooled in the minutiae of the characters or their past television lives. Weirdly enough, while relying on the audience’s assumed knowledge of the show, the movie also eliminates a lot of key narrative elements from the series, including the crucial love triangle between Sam, Jayden, and Holiday (who is gone completely missing in the movie), and in the film Sam and Jayden don’t even appear together. The film’s story consists of three vignettes featuring Sam, Jayden, and newcomer Branson (played by the inexpressive Louis Koo) which don’t interlock in any meaningful way. Aside from one scene, none of the male leads interact with each other, and Jayden seems to be on another continent for the entire film. Each of the vignettes lack any kind of dramatic tension, with almost nothing at stake for the characters, and they resolve in the most predictable ways possible. The film as a whole is missing self-awereness, irony, wit, or anything that might add a bit of an edge to the film, and the three narratives play out like long-form wristwatch adverts, with gratuitous product placements of bottled water, designer chocolates, and jd.com, the Chinese shopping site that miraculously ships within hours from Asia to London.

The lead actors don’t look too bad for their age (with Francis in his fifties and Chilam and Louis both mid-forties), and Charmaine Sheh and Sammi Cheng as the love interests are feasible and not too mismatched. Amber Kuo as Jayden’s girl-toy appears to be way too young for him, though, and their vignette in particular is pretty cringeful, relying on a remarkably tired plot twist and saddling poor Chilam with horribly clichéd romcom dialog about hearts living in other people’s bodies and the like. Sammi Cheng as a pop star (what?) is cool with her tattooed knuckles and hard-part eyebrow and she and Francis make a pretty pair, but the impetus for their hook-up is completely contrived. As a fangirl I did enjoy the sight of Sam Gor practicing his dance moves, but the question still remains: WHAT HAPPENED TO HIS FORMER GIRLFRIEND? There is also a gratuitous subplot involving a pair of mainland Chinese characters that concludes in the cheesiest way possible and which seems tacked on just so the PRC audience can hear a bit of Putonghua (inexplicably, the actor playing Louis Koo’s father also speaks Mandarin, though Louis Koo’s dialog is strictly in Hong Kong Cantonese).

As usual Francis does his thing, acting with his mouth full of food and with his eyebrows quirked, but honestly he doesn’t have a whole lot to do. There’s also a tiny bit of TITS fan service with Kenneth Ma and Elena Kong reprising their characters from the television drama and Kenneth Ma is anonymously humorous in the twenty seconds that he’s onscreen, but their appearances only underscore the calculated genesis of the film, in which the producers are trying to suck in as many customers as possible.

The entire viewing experience is like injesting an extra-large serving of Kraft Cheese Food Sticks, with lens flare, rainbows, designer clothes, and saturated color correction making for a pleasant but ultimately vacuous optical experience. Coming from a straight-up fanperson like myself who really wanted to like this movie, I think that, for all of its interminable schmaltziness, the TVB drama is actually a better product, since at least it had some interesting character conflicts and gave its performers space to emote a bit. The movie version is all hat and no cattle, with beautiful sunsets and ferris wheels and not much else. But the movie was number one at the box office in Hong Kong during the Lunar New Year holiday and made more than 100RMB during the same time period in China, which bodes well for Francis Ng and his rebooted career. He’s currently working on a film with Zhou Xun, he recently wrapped another Chinese romcom, Love Without Distance (directed by Hong Konger Aubrey Lam), and there’s already talk of another film sequel to TITS (noooooo!) Meanwhile, the Chinese film commerce machine rolls on, as TVB is planning to cash in with a movie version of another one of its recent dramas, Line Walker, with Nick Cheung and Lau Ching Wan rumored to star.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that a mainstream movie like TITS is so overtly commercial, but being an optimist I always hope that these undertakings might squeeze in a bit of craft and care and maybe even some genuine artistry. No such luck here, but kudos to Francis Ng for riding the wave and coming out on top once again.

Lost In Love: Back In Time movie review

Classic Chinese pop music, known as Cantopop or Mandopop depending on the dialect, is a bit of an acquired taste. It’s all smooth edges and soft sounds, designed to soothe and comfort, as opposed to, say, the techno-hip hop flavors of Kpop. It’s no surprise that Western imports like Air Supply, kings of the power ballad, are hugely popular in China and Hong Kong. There are of course exceptions to this, including the hard-rocking Cantopop kings Beyond, but the top of the charts in Hong Kong as well as on the mainland have since the 1980s been dominated by sleek pop balladeers such as Jacky Cheung, Faye Wong, and Andy Lau.

The cinematic equivalent of Canto/Mandopop would be Back In Time, (aka Fleet of Time), which recently played here in the U.S. as a day and date release with China. The film was number one at the box office in China before being bumped off the top spot by Jiang Wen’s Gone With The Bullets. Like a lot of Chinese pop music, Back In Time is competently crafted and pleasant to experience, but soft and cloying, without a lot of rough edges.

A slick weepy with attractive leads in Eddie Peng (most recently seen kicking ass in The Rise of the Legend and Unbeaten, among other manly roles) and Nini (chief flower in Zhang Yimou’s Flowers of War), Back In Time is unabashedly nostalgic as it traces the relationships of a group of friends from their high school days to adulthood. The main narrative follows the reminiscences of businessman Chen Xun (Peng) as he recalls his chaste adolescent romance with the Fang Hui (Nini), a transfer student to his secondary school. Although the two promise everlasting devotion, for the sake of narrative tension their romance hits the skids. Will they kiss and make up or will they forever be lost to one another? The film’s gauzy, soft-focus shots of billowing curtains, rain-slicked streets, snowy landscapes, and characters literally crying in their beer heighten the overall sentimentality of the proceedings.

The movie is also fairly apolitical, despite spanning a period of great change in Chinese history (roughly 1999 to the present day). Although China went through a lot during that time, almost none of this is present in the film (except a reference to Beijing’s winning bid to be the site of the 2008 Olympics). Instead the film focuses on its youthful love story, which strips the narrative of most of its historical context and content. Compared to Taiwan’s similarly structured Girlfriend/Boyfriend (2012), which actively incorporated student political demonstrations into its story, Back In Time only briefly touches on events that occurred during its timeline. The rest of the film takes place in a historical vacuum, with the passage of time primarily reflected in the changing hairstyles and cell phones of the protagonists (with wigs worn with varying degrees of success, including Eddie Peng’s ill-fitting late-90s mop and Nini’s curiously changing hair lengths).

Lead by the pretty leading pair played by Peng and Nini, the film’s cast is winning and earnest, though in the earlier parts of the movie some of the performers look way too old to be high school students. There are also a few confusing plot developments such as a hissy fit at an outdoor restaurant that escalates without explanation into a knock-down brawl, but none of them as contrived or annoying as those found in the Nicholas Tse/Gao Yuan Yuan romantic drama stinker, But Always. But Back In Time, though by no means racy, also deals fairly frankly with sexuality, a change from many similar melodramas of its ilk that’s worth a few points in my book. At times the overwrought emotionality of the movie just barely avoids self-parody and isn’t helped by the swelling violins and tinkly piano on the soundtrack. But it’s a watchable timepass, especially if you’re in the mood for a deeply emo cinematic experience.

With Back In Time, distributor China Lion continues to hit its stride. Unlike the typical Asian genre fare of gangster, martial arts, and wuxia films usually distributed in the U.S. and aimed at Western sensibilities, CL’s most recent releases aim straight for the Chinese expat community. Its last five titles released in 2014—Back In Time, Women Who Flirt, Love On A Cloud, Breakup Buddies, and But Always—are romantic dramas or comedies and feature performers popular in China but mostly unknown in the U.S. even among Asian film aficionados, with the exception of Nicholas Tse and possibly Zhou Xun. These movies also differ from the output of international arthouse favorites like Zhang Yimou or Chen Kaige and are solidly middlebrow and commercial, created to entertain and not to startle, and have found an audience in the U.S. Deadline.com notes, “China Lion has had success with romantic dramas imported from Chinese-speaking regions in the past. They handled Beijing Love Story ($428K cume) in February and other past titles include Love ($309K cume) and Love In The Buff ($256K cume).”

Back In Time (as well as the CL releases that immediately preceded and follow it, Pang Ho-Cheung’s Women Who Flirt and the Angelababy vehicle Love On A Cloud) demonstrates that China Lion has figured out a winning formula that works for its Chinese expat niche audience. Though many of these films may not be appealing to the typical Asian-film fanboy in the U.S., to Chinese audiences away from home they’re just like listening to the latest Jacky Cheung CD—they’re a soothingly familiar entertainment experience.

Tiger By The Tail: The Taking of Tiger Mountain movie review

Legendary director Tsui Hark has been a fixture on the Hong Kong cinema scene since the 1970s (except for a little hiccup in the 90s when he made a couple crappy Hollywood movies with Jean Claude Van Damme, but let’s not talk about that now). His string of significant cinema work started in 1979 with The Butterfly Murders, moved through the 1990s with a slew of indispensible films including A Better Tomorrow (producer), A Chinese Ghost Story (producer), and the Once Upon A Time In China series (director), and continues to the present day with a clutch of period action films including Detective Dee 1 & 2 and Flying Swords of Dragon Gate. His latest joint, The Taking of Tiger Mountain, just opened in the U.S. a week after its successful debut in China, where it’s the top film at the box office.

The film is based on a popular Beijing opera (from the novel Tracks in the Snowy Forest) that was one the Eight Model Plays sanctioned by Mao during the Cultural Revolution. The opera was adapted into a film in 1970 that Tsui Hark, along with most of China’s other 800 million people at the time, viewed as a youth. Tsui’s current adaptation is a co-production of the heavy-hitting commercial studio BONA Film Group and the August First Film Studio, which is the film-producing branch of China’s People’s Liberation Army, and the influence of these disparate financing sources shows in the finished product. While it mostly passes as an energetic action/adventure movie, Tiger Mountain also has the smell of Chinese military propaganda, which inhibits some of director Tsui’s more maverick instincts.

The story is based on a true incident that took place in 1946 during China’s civil war, in which a small platoon of PLA fighters overcame a much larger bandit crew (alluded to as affiliated with the Kuomintang, the PLA’s opposition during the civil war) that’s holed up in a mountain stronghold. The film opens with a framing device in which Jimmy (Han Geng), a young modern-day Chinese student in the U.S., sees a snippet of the 1970 Taking Tiger Mountain film. As his buddies laugh at the old-fashioned opera stylings, Jimmy smiles fondly and later watches the film on his phone as he travels home to Harbin. The movie then cuts to the main action as the PLA platoon struggles to protect a village from the KMT bandits while confronting a lack of food and supplies as well as the onset of winter. As the situation worsens the platoon’s leader, known only as 203, decides to storm the bandit’s hideout on Tiger Mountain, sending in Yang (Zhang Hanyu), a PLA intelligence agent, to infiltrate the gang. The main body of the film follows Yang as he works from within the bandits’ lair while his compatriots endeavor to attack the stronghold from without. After a somewhat slow setup the narrative picks up speed around the forty-minute mark once Yang makes his way into the good graces of the bandit leader, Hawk. Following much intrigue and double-crossing the film concludes with a rip-roaring battle in the snowy mountain as the heroic PLA troops clash with the diabolical KMT bandits.

Tiger Mountain was released in China in 3-D (although its U.S. release is only in 2-D), and the film’s first brief battle sequence feels a bit too gamish, with slo-mo bullet-cam shots and computer-animated blood spurts probably better appreciated stereoscopically, The later, more extended action sequences, including an outstanding siege of a small village, are more engaging and rely less on CGI and more on real hand-to-hand combat and kinetic fight choreography. The climatic battle sequence and a brief coda involving a runaway plane are both pretty thrilling and demonstrate Tsui’s sure hand with action, characters, and special effects.

Tsui draws out solid performances throughout, although some of the film’s characters fall into standard war-movie types. Zhang Hanyu is dashing and resourceful as Yang, the fearless PLA spy sent to infiltrate the bandit camp, and he has several outstanding moments that convincingly demonstrate Yang’s ability to think on his feet. Tony Leung Ka-Fai plays a few years older in a bald-wig and hook nose as Hawk, the ruthless bandit leader, and it’s great to see him sink his teeth into the meaty character role. Lin Genxing is forthright, square-jawed, and handsome as the platoon’s captain but otherwise isn’t terribly compelling. Yu Nan doesn’t get to exercise her usual steely bravado since she’s mostly a captive throughout, though she does escape her bondage several times during the course of the film. Tong Liya as Little Dove, the doughty nurse, is predictably brave and lion-hearted. There’s also a cute little traumatized kid who gets to play a heroic role in the last battle as well as provide a manipulative emotional moment at the film’s climax.

As a Western viewer it’s a bit odd for me to root for the PLA since in my mind the Chinese army is forever linked with the 1989 brutality of Tiananmen Square, but PRC audiences undoubtedly have more positive associations with China’s military. Chinese viewers also probably feel a more visceral response to the strains of the familiar revolutionary opera on the soundtrack and find kinship with Jimmy and his nostalgic journey home to rediscover his family’s PLA roots.

In fact, Jimmy can be seen as a surrogate for Tsui himself, as at the outset of the film he recalls his nostalgic U.S. encounter with the original Taking Tiger Mountain film. Later, at the film’s conclusion, Jimmy is surrounded by a cadre of PLA soldiers and can only smile helplessly, submitting to the collective PLA memories, even as he tries to re-imagine a different version of the narrative’s conclusion. The PLA perspective, and by extension the August First version of the story, is too overwhelming to contradict.

Under different circumstances Tsui really could’ve cut loose but may have felt constrained by the sanctity of the material and/or by the military film office breathing down his neck. The film is much less irreverent and less of a pointed critique than some of his earlier productions that scathingly sent up organized religion (Green Snake), corrupt government officials (New Dragon Gate Inn), and colonial malfeasance (Once Upon A Time In China). Nonetheless, hints of Tsui’s signature style sneak in via the Road Warrior-esque bandit fashions including mohawks, facial tats, and various other quirky costuming choices that recall the art direction of Tsui’s earlier films including The Blade. Another glimpse of the film that might have been is an electrifying throwaway coda involving a speeding fighter jet, a long tunnel, and a very high precipice. Still, The Taking of Tiger Mountain is nowhere near as heinously patriotic as earlier glossy August First propaganda productions like The Founding of A Republic from a few years back. It’s to Tsui’s credit that he’s able to create a highly watchable and sometimes exhilarating film, however restricted he may have been by his material and his funding sources.

Drunk In Love: Asian Males in Hiroshima Mon Amour and The Crimson Kimono

As Asian American film scholar Celine Parreñas Shimizu notes, there is “a long tradition in Hollywood movies of iconic portrayals of Asian American men (as) rapacious and brutal, pedophiliac, criminal, treacherous and also romantic, and quaint. Sexuality and gender act as forces in the racialization of Asian American men.” Sadly, despite tiny steps towards improvement, Asian male representation in Hollywood still remains timidly entrenched in stereotypes. Sure, John Cho is the leading man in Selfie, (although he’s already starting to be a bit stalkerish), and Glenn (Steven Yeun) from The Walking Dead is still alive and human (though there are persistent rumors of his imminent demise), but on the big screen the ridiculously hot Lee Byung-Hun is still playing the bad guy (most recently in the upcoming Terminator: Genisys) instead of fulfilling all of our fantasies as a romantic lead.

Strangely enough, our modern era is in some ways more regressive than, say, 1959. Althought the 1950s weren’t known for their progressive portrayals of Asian Americans in Western films, in that year Asian men appeared as objects of desire in two significant movies. In 1959 the Hawai’ian born Sansei actor James Shigeta made his big-screen debut in Sam Fuller’s film The Crimson Kimono, playing a Los Angeles detective assigned to the case of a murder of an exotic dancer. The film is an engaging cop movie but it’s most notable for its portrayal of a love triangle involving Shigeta, his white partner Sgt. Charlie Bancroft, and Bancroft’s girlfriend Christina, who is also white. Unlike most such romantic conflicts involving an Asian man opposite a white guy, in this case Shigeta got the girl, which made The Crimson Kimono a groundbreaking anomaly in Hollywood. James Shigeta was a co-winner of the 1960 Golden Globe Award for Most Promising Male Newcomer and he would go on to a moderately successful career as a romantic lead for a few years but he never became the superstar that his good looks and charisma would indicate. Like most Asian American men in Hollywood up until and after that time Shigeta ran into the impenetrable glass ceiling of racism.

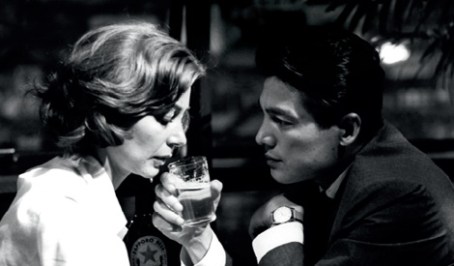

1959 also saw the depiction of another desirable Asian male, in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour. In that film Eiji Okada plays the intensely romantic Lui, a Japanese architect who has a brief and torrid affair with a Frenchwoman played by Emmanuelle Riva (seen most recently in Michael Haneke’s Amour). With a screenplay by noted Asiaphile Marguerite Duras (L’Amant/The Lover; Un barrage contre le Pacifique/The Sea Wall), Resnais’ film depicts Lui as suave, tender, and desirable, which contrasts greatly with the ways that Hollywood has typically portrayed Asian men. Okada is particularly swoonworthy as he and Riva’s character passionately discuss love, war, genocide, and beauty, against the backdrop of the site of first the atomic bomb attack. With the ruins of Genbaku Dome in the background, the film also utilizes a nonlinear narrative structure that links the European front, as exemplified by a long flashback set in France, to the Pacific theater, with Hiroshima repping for all of Japan. Set some fifteen years after the end of World War II, the film emphasizes the human cost of the war even many years after its ceasefire, as both Lui and Elle have been scarred by the loss of loved ones in the conflict. Elle fetishizes both her late German lover and Lui, as she is drawn to them due to their difference and otherness.

Now releasing theatrically for the first time in years in a new 4K digital restoration, Hiroshima Mon Amour remains fresh and relevant both thematically and stylistically (it’s regarded as one of the most influential films of the early Nouvelle Vague, or the French New Wave). It’s also an example of an early representation of an Asian male as not a caricature, a villain, or a clown, but as a fully fleshed out, highly desirable romantic lead. Now if only Hollywood could get a clue and do the same in the 21st century.

Opens October 31

3290 Sacramento St.

San Francisco CA

(415) 346-2228

Love Hangover: Temporary Family and But Always movie reviews

A couple Chinese-language romantico films made their way into the U.S. market this week and one works while the other doesn’t. Hong Kong release Temporary Family uses the backdrop of the superheated HK real estate market to frame its romantic comedy, while PRC rom-dram But Always flails about in China and the U.S. as it attempts to tell its story of lovers pining for each other across years and continents.

Hong Kong renaissance woman Cheuk Wan Chi (aka Goo-Bi GC aka Vincci aka G) directs Temporary Family, an amusing romcom starring A-listers Nick Cheung and Sammi Cheng, along with mainland Chinese starlet Angelababy and rapper/singer Oho (who sings the title track). A broad, hyperlocal comedy that sends up the tight housing crunch in the former Crown Colony, the movie also includes cameos by Heavenly King Jacky Cheung, TVB stars Myolie Wu and Dayo Wong, and Chinese film star Jiang Wu (as an ultrarich PRC real estate speculator) and, not surprisingly, the movie has been a huge hit in its home territory. Although the film tilts towards the slapstick at times it still manages to sustain its narrative tension for most of its running time and is an agreeable timepass. Nick Cheung (Lung) started his career back in the day as a Stephen Chow wannabe so it’s not surprising to find him successfully tempering his usual dramatic intensity in a lighter comedic role. Sammi Cheng pulls out her neurotic jilted lover persona most famously seen in Johnnie To’s huge romcom hit Needing You, this time playing Charlotte, a recent divorcee unable to break from the past. Angelababy plays Lung’s adopted daughter, a slouchy millennial who bounces aimlessly from one low-paying job to another. Oho rounds out the main characters as the awesomely named Very Wong, Lung’s intern and the scion of an unnamed rich man in China. The plot contrives to throw together this unlikely crew as temporary roommates in a luxury condo in Hong Kong’s toniest neighborhood as they attempt to cash in on the real estate market’s volatility.

The movie is chock full of local references and in-jokes (why do all the real estate agents have bleached blonde hair?) and follows the time-honored Hong Kong movie tradition of good-natured vulgarity, including a running joke about a stray pubic hair. Structurally the film recalls the slackly constructed, improvisational comedies of Hong Kong Lunar New Year films and, maybe due to director G’s relative inexperience (this is her second feature), at times scenes abruptly and inexplicably fade to black. Though the movie’s energy flags a bit about two-thirds in, the amiable cast powers through the rough patches and manages to pull out a reasonably entertaining conclusion including the sardonic last scene, as Lung and Charlotte finally find their bliss. Nick Cheung as the desperate realtor Lung is as always quite watchable. Sammi Cheng is somewhat less so, as her neuroticness precludes much lovability, which in turn spoils any chemistry she and Nick might have had.

The movie has been a big hit both in Hong Kong and the PRC, and it’s great to be able to see it here in the U.S. on the big screen, if only to ogle the panoramic shots of Hong Kong harbor and its skyline at night. I had no luck tracking down the U.S. distributor so I was a bit surprised when it popped up here at the Metreon, but I’m glad that I ran across its screening schedule in a random facebook post. It looks like some Chinese distributors are following China Lion and Wellgo’s lead in targeting the Chinese-speaking audience here in the States, although their choice of films is somewhat random. But I’ll take what I can get, especially if it means releases of non-action films like Temporary Family and Pang Ho-Cheung’s Aberdeen, which showed up without fanfare down in Santa Clara a month or so ago.

Like those two films, the Nic Tse/Gao Yuan Yuan romantic vehicle But Always had a day-and-date release here in the Bay, but the movie is no great shakes and is in fact one of the worst, most hackneyed and clichéd films I’ve had the misfortune to witness in a long while. Granted, I don’t go see a lot of romantic films, since my preference is for movies with guns and gangsters, but I know a bad movie when I see one. Not only is the storyline derivative and the narrative conflict forced, but the characters are poorly drawn and the film’s direction is sloppy and amateurish.

The movie starts in 2001 in New York City, then flashes back to 1970s Beijing where Anran (Gao Yuan Yuan) and Yongyuan (Nic Tse), are young kids. This is the best part of the film as the movie renders mid-century China as comfortably shabby and not yet touched by modern global capitalism. The movie then laboriously follows Anran and Yongyuan’s relationship through the years in both China and the U.S. as they hook up, fall apart, and reconcile numerous times for no apparent reason except to generate dramatic angst. The film trowels on the melodrama as suicide attempts, love triangles, jilted lovers, and other tragedies mount. The only things missing from the hit parade of drama trauma are amnesia, long-lost twins, and a car crash, though the ending surely tops these in its maudlin, fatalistic conclusion. Hint: the date and place of the lovers’ last rendezvous gives away the fantastically tragic coincidence at the film’s climax.

Nic Tse and Gao Yuan Yuan are nicely lit and photographed throughout, though Nic seems a bit embarrassed to be in such a crappy flick. It’s also funny to note that, being a PRC production, we get to see his a lot of his beautiful torso and cut abs but almost none of her naked skin except a decorous peek at her bare shoulder.

There’s nothing wrong with the old-time narrative of star-crossed lovers patiently waiting for each other through endless adversity and I’m all for a well-told version of a classic story, but this movie is not that. Instead it’s a lazy, clumsy rehash of tired tropes without any freshness, originality, wit, or style. Yeah, I didn’t like it much.

Kings of the Wild Frontier: Roaring Currents and Kundo review

Three huge South Korean historical actions films have been breaking box office records in their home territory this summer, and we lucky dogs here in the U.S. also have a chance to see them on the big screen.

The first one that rolled through town, opening in San Francisco on Aug. 15, was The Admiral: Roaring Currents. Though no longer playing in SF proper (it’s still showing in Santa Clara and Dublin) the film had a good two-week run at Metreon and Century Daly City. I saw a matinee at Metreon before it closed and was pretty swept up by the sheer muscular grandeur of dozens of sixteenth-century wooden ships in close battle around a raging whirlpool. The movie is a tightly made film full of rousing action, noble sacrifices, and heroic nationalism, as the Joseon navy, reduced to twelve ships after a series of disastrous battles, goes at it against a Japanese invading force of more than two hundred ships. Since it’s all about Korean national pride against the evil imperial Japanese military, the Koreans are scrappy underdogs with mud-streaked faces and rough-hewn sea vessels, while the Japanese are sneering, spit-and-polished marauders in gilt-trimmed ships.

Based on the true exploits of the titular character, legendary Joseon naval commander Yi Sun-Shi, the loosely follows the Battle of Myeongnyang, which took place in 1597 at a strategically important strait off the coast of modern-day Korea. The film spends about half its two-hour running time setting up the various characters and their narratives, then jumps into a series of battles and skirmishes that take up the second hour of the film. These sequences are loads of fun, with wooden-ship ramming, whirlpools, hand-to-hand combat, flying arrows, cannonballs, and flaming boats full of explosives, but the focus remains on the stalwart Admiral Yi, played with gravity and authority by the redoubtable Choi Min-Sik (Oldboy). Also good are Jin Goo as Joseon scout Im Jun-yeong and Cho Jin-woong as Japanese baddie Wakisaka Yasuharu. Director Kim Han-min, whose last film War of The Arrows (2011) was also an hyperkinetic historical, keeps everything moving along at a brisk pace, with escalating skirmishes building to a rip-roaring climax. Roaring Currents is now the highest grossing movie of all time in South Korea, breaking the record previously held by Avatar.

The second South Korean costumed adventure, Kundo: Age of the Rampant (what?) opened this Friday in the U.S. and it also follows a bunch of scrappy underdogs fighting the power. This time the story is set in the 19th century Korea and follows a Robin-hoodlike group named Kundo who stand up for the oppressed peasantry against corrupt nobles and their politician lapdogs.

The film is much more loosely plotted and constructed than Roaring Currents, and director Yoon Jong-bin has a jokey, self-conscious directing style that recalls Takashi Miike without the sadism and misogyny. Yoon riffs on classic Westerns, with a twangy, guitar-based Morricone-esque theme song and good and bad buys fighting on horseback, but adds in some nice swordplay choreography and decent hand-to-hand, sword-on-cleaver action, as well as a good helping of Hong Kong-style martial arts. His cartoonlike direction includes extreme zooms in and out, jump cuts and speed-ramping, and a villain who is only missing a waxed mustached to twirl. The script included lots of anachronistic cursing that translates in the subtitles as a bunch of f-bombs, which only adds to the Brechtian fun.

Though somewhat rambling in its narrative, the film is ultimately an entertaining eastern Western, anchored by Ha Jung Woo as Dolmuchi, a doofy butcher who mixes it up with Jo Yoon, the unacknowledged bastard son of the corrupt local nobleman running Dolmuchi’s district. At 36 years old, Ha is way too old to convincingly play an eighteen-year-old, especially compared to his dewy-eyed adversary, played by Kang Dong-won who with his feline androgyny is entirely plausible as a nineteen-year-old. Nevertheless Ha is fun and fierce as the bumbling butcher turned hero who is recruited by the Kundo vigilantes as they stick up for the rights of the peasants against the corrupt and exploitative nobles. The film gestures toward empowering the common people but ultimately it’s just a lot of silly fun that’s entirely worth seeing on the big screen.

The third of this year’s South Korean historical blockbuster trilogy, The Pirates, arrives in U.S. theaters on Sept. 12 and a review will be forthcoming once I see it. When it rains, it pours, though I’m certainly not complaining.

The Admiral: Roaring Currents

Regal Hacienda Crossing Stadium 20 & IMAX

5000 Dublin Blvd.

Dublin CA

AMC Cupertino Square 16

10123 N. Wolfe Rd.

Cupertino CA 95014

Kundo: Age of the Rampant

AMC Cupertino Square 16

10123 N Wolfe Rd

Cupertino, CA 95014

Century 20 Daly City

1901 Junipero Serra Blvd

Daly City, CA 94015

Four Star Theatre

2200 Clement St

San Francisco, CA 94121

Typical Girls: Kenji Mizoguchi film series at the Pacific Film Archive

The Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley comes through once again with another outstanding series, this time focusing on legendary Japanese filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi. Running through the end of August, this set gives you the chance to see much of Mizoguchi’s amazing oeuvre on the big screen and in glorious 35mm.

Along with Akira Kurosawa and Yasajiro Ozu, film historians consider Mizoguchi one of the Holy Trinity of golden-age Japanese filmmakers—the work of these seminal directors spanned much of the early and mid-twentieth century and has received massive critical attention. Among those three, however, Mizoguchi’s star has dimmed a bit, due in part to the somewhat unrelenting bleakness of his films. But his portrayals of the plight of women in a patriarchal society are pretty key, and his intricate camerawork and direction are still fresh and revelatory. The PFA series is a great chance to witness Mizoguchi’s masterful use of the filmic medium to examine the effects of a brutal and uncaring society on individuals caught in its strictures.

Mizoguchi’s brilliant use of the camera is in full effect throughout the series. Famous for including a minimum of close-ups and often shooting his scenes in extended master shots (a style dubbed “one scene, one cut”), he performs a kind of cinematographic butoh, with ultra-slow, beautifully choreographed push-ins, pans, and dollies that mesh with the characters’ actions and dialog in an intricate, intertwined choreography.

The PFA series include most of Mizoguchi’s well-known jidai-geki (historical dramas) like the popular ghost story Ugetsu, winner of the Silver Lion Award for Best Direction at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, and The Life of Oharu, a masterpiece that’s a sad tale of a woman’s oppression, told with clockwork precision and driven by a bravura performance by Kinuyo Tanaka. In addition to his more famous historicals, the PFA is also screening several of Mizoguchi’s modern-day films. Mizoguchi is recognized for his period pieces, yet like his compatriot Akira Kurosawa he also directed several films that scathingly examine issues and problems of 20th-century Japan. As with his period films, these modern-day movies often center on the plight of women in a straight-laced society. Osaka Elegy (1936) is a bleak, brilliant, and economical portrayal of the social strictures that constrained women in a pre-feminist age. Elegy is buoyed by Mizoguchi’s sympathetic portrayal of the female protagonist, surrounded by exploitative, weak, or cowardly male figures who lend little support when the heroine falls on hard times. A proto-noir filled with deep shadows and geometric compositions, the film displays Mizoguchi’s mastery of the medium even in the 1930s.

Also from 1936, Sisters of the Gion is a surprisingly modern and unsympathetic take on the hard-knock geisha life, full of Mizoguchi’s gliding camerawork and one-take marvels. Hard-as-nails Omacha and her more sensitive sibling Umekichi are two low-end geisha in the Gion, Kyoto’s licensed pleasure district, who are struggling to make ends meet by landing “patrons,” customers who are mostly old wizened married guys. The film is a cutting indictment of the capitalist system that’s all about the money and is a good example of a Mizoguchi keikō-eiga (tendency film), which literally displays his socialist tendencies. Omacha is the deal-maker, trying to manipulate the system to escape the oppression of poverty, sexism, and misogyny, while Umekichi desperately believes that the system will work in her favor. The PFA series screens Mizoguchi’s remake of Sisters of the Gion, A Geisha (1953), which updates the story to postwar occupied Japan and which stars the famed Ayako Wakao in one of her first film roles.

The PFA series concludes with Mizoguchi’s last movie, Street of Shame (1956), which is an excellent example of Mizoguchi’s use of film to examine social problems. The story concerns a group of prostitutes in postwar Tokyo who struggle to overcome an andocentric culture insensitive to the needs of women. In a role that’s a departure from her parts in the period films Rashomon and Ugetsu, Machiko Kyo plays Mickey, a material girl who’s not above stealing her co-workers’ customers or blithely overextending her credit at local shops. Ayako Wakao as Yasumi is a no-nonsense working girl who plans to escape the brothel by becoming a moneylender and shopkeeper. The men in the film are for the most part weak, craven, or venal, preying on the female protagonists and only valuing them for their bodies or their beauty, or despising them for their vocation. Yet Mizoguchi makes it clear that the women are prostitutes only because they are given little other choice in society. In one amusing scene one of the women who’s left the profession to marry a small-town cobbler returns to the brothel. She laments that marriage is worse than selling her body to strangers as her husband forces her to work in the shop from morning to night, then expects dinner and sex at the end of the day. Mizoguchi’s narrative uses the women’s plights as a critique of capitalism, an exploration of the uncertainty and despair of post-war Japan, and an indictment of the constraints of a patriarchal society.

While many of Mizoguchi’s films are available on DVD, Mizoguchi is absolutely a big-screen director. His subtle use of the camera and his epic portrayals of women and men struggling to overcome their fate deserve to be appreciated in a movie theater and, as usual for this excellent venue, the PFA serves up his films as they were meant to be seen.

Kenji Mizoguchi: A Cinema of Totality

June 19, 2014 – August 29, 2014

Pacific Film Archive

2575 Bancroft Way

Berkeley CA 94720

Recent Comments