Posts tagged ‘movies’

Willing: New Lav Diaz film at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

I did not come willingly to Lav Diaz. My personal cinematic preferences run to fast and economical 90 minute Hong Kong action films—one of my favorite films is Johnnie To’s 84-minute gangster flick The Mission, which manages to complete its main narrative arc in about 50 minutes, with a 30 minute coda tying up the loose ends. So the idea of sitting through a film by a director known for his ten-hour epics wasn’t high on my list of things to do, and while I wasn’t exactly kicking and screaming when I was talked into attending my first Lav Diaz film, I did approach it with some trepidation. But after experiencing that film, the 4.5 hour Norte: The End of History, I was hooked.

I actively sought out my second Lav Diaz experience (which is the best way to describe viewing his films), the 2014 documentary Storm Children: Book One, which I thought was pretty brilliant. Despite its relatively brief running time of 2.5 hours the film is still an immersive experience, shot in black-and-white and with very little spoken dialog. As in Norte, Diaz uses extremely long, mostly stationary shots to emphasize the action within the frame, which at times consists of very little action at all. Recording the aftermath of 2013’s Typhoon Yolanda (also known as Haiyan) on the seaside village of Tacloban, Diaz’s technique makes the viewer become an active participant in the revelations of the film. The documentary opens with a long static shot of cars driving through water that has all but submerged the roadway, the sound of the swishing tires comprising most of the soundtrack. Following this, Diaz’s camera observes a couple kids as they attempt to fish something out of a fast-moving stream of flotsam below a bridge. This takes possibly twenty and up to thirty minutes of screen time. Another sequence documents more kids digging a mysterious hole in a great mound of sand or shale, very gradually unearthing various items that are never really identified. Again, this sequence runs for very many minutes with almost no camera movement or edits. The effect of these extremely long static takes induces an almost palpable shift in the ways one views a film—instead of the brief and restless, cursory absorption of a surfeit of visual information, the viewer sinks into reading a few simple yet significant actions. This type of perception is almost hypnotic and literally alters the consciousness of the audience, making the viewer’s experience highly visceral and immersive.

Diaz’s slow-burning technique also allows viewer to make significant narrative and visual discoveries at their own pace—he lays out the information without overtly drawing attention to it, which allows viewers to puzzle out the meaning themselves. A great deal of the latter part of Storm Children takes place near the shoreline where kids play amongst huge ships. It takes a while to realize that the ships are all aground, some many, many yards onto dry land, and that the typhoon’s force beached them with its immense strength and violence. It’s a thrilling and singular way to receive cinematic information and adds a depth and level of intellectual and visceral participation to the viewing experience like no other.

Thus it’s with high expectations that I go now to my next Lav Diaz screening. Upcoming as part of the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts New Filipino Cinema series, From What is Before (Mula sa kung ano ang noon), which won the top prize at the 2014 Locarno Film Festival, screens June 27 and 28. A black-and-white narrative about the early days of dictator Ferdinand Marcos’ regime and its effects on a remote village in the Philippines, the film again utilizes very long, almost static shots and black and white cinematography. As with previous Diaz films the telling is as important as the tale, and the tale here, the advent of Marcos’ despoiling of the Philippines, is very important indeed. It’s a rare chance to go through the immersive experience of a Lav Diaz theatrical film screening and is not to be missed.

From What is Before (Mula sa kung ano ang noon)

dir. Lav Diaz, 338 minutes

June 27 & 28, 2015

2pm

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

I Would Die 4 U: Black Coal, Thin Ice at the San Francisco International Film Festival

Just got back into town and am diving into the thick of things at this year’s San Francisco International Film Festival, now running through May 7. I’m leaving town again on Sunday so I’m cramming as many screenings into the next five days as I can manage. Luckily there are plenty of great films to see. I’m hoping to make it to the Viggo Mortenson vehicle Jauja, by Argentine director Lisandro Alonso and featuring Viggo in a role that’s tailor-made for him as a Danish military engineer caught up in unrest in 19th-century Patagonia. Viggo he gets to acts in two of his native tongues, Danish and Spanish, and the film is a magical-realist version of the historical events it depicts.

Also on the docket is the 3-D version of Tsui Hark’s The Taking of Tiger Mountain, Hong Kong director Peter Chan’s child-abduction drama Dearest, and City of Gold, the documentary about Pulitzer-prize winning Los Angeles food critic and mensch Jonathan Gold. If I were in town next week I’d surely go see the South Korean thriller A Hard Day but I’m hopeful that it will make it to a theatrical release stateside sometime soon. SFIFF also plays host to Jenni Olsen’s newest feature-length experimental documentary/essay film The Royal Road, which looks at butch longing and unrequited love against the backdrop of El Camino Real, the historic king’s road that stretches nearly the length of California. Indian director Chaitanya Tamhane’s independent feature Court also screens this week, taking a character-based, neo-realist look at the absurdities of the Mumbai judicial system and its surrounding social and cultural milieu, with results that are about as anti-Bollywood as you can get.

One of my favorite films from last year, director Diao Yinan’s neo-noir Black Coal, Thin Ice, has one more screening this week at the festival and it’s definitely a don’t-miss movie. From the very start, with shots of random body parts mixed in among train cars of coal shipping throughout the frozen northern regions of China, the film puts a distinctive spin on the classic noir structure. The film follows Zhang (Liao Fan), a less-than-scrupulous cop, as he becomes more and more deeply involved in the mysterious disappearances and murders of various hapless men, all of whom eventually seem to be tied to a classic black-widow character, played by the amazing Taiwanese actress Guey Lun-Mei.

Looping back and forth in time and place, with bursts of intense and unexpected violence, the movie effortlessly transfers the noir genre to the China’s bleak and wintry industrial north, making great use of the icy landscape and the characters’ corresponding desperation and hopelessness. Both Liao and Guey won acting awards (at the Berlin Film Festival and the Golden Horse Awards respectively) for their performances in this film and they embody the moral messiness and ambiguity of the best noir characters. As in all great noirs, everyone is complicit and no one is innocent, and the most innocuous situation, whether in a beauty parlor or at an ice skating rink, can suddenly change into a deadly trap.

So although I’m missing the big galas and parties at the beginning and end of the fest I’m still catching the meat of the event this week. As always the festival is a chance to see some of the best recent global cinema on the big screen.

58th San Francisco International Film Festival

through May 7, 2015

Drunk In Love: Asian Males in Hiroshima Mon Amour and The Crimson Kimono

As Asian American film scholar Celine Parreñas Shimizu notes, there is “a long tradition in Hollywood movies of iconic portrayals of Asian American men (as) rapacious and brutal, pedophiliac, criminal, treacherous and also romantic, and quaint. Sexuality and gender act as forces in the racialization of Asian American men.” Sadly, despite tiny steps towards improvement, Asian male representation in Hollywood still remains timidly entrenched in stereotypes. Sure, John Cho is the leading man in Selfie, (although he’s already starting to be a bit stalkerish), and Glenn (Steven Yeun) from The Walking Dead is still alive and human (though there are persistent rumors of his imminent demise), but on the big screen the ridiculously hot Lee Byung-Hun is still playing the bad guy (most recently in the upcoming Terminator: Genisys) instead of fulfilling all of our fantasies as a romantic lead.

Strangely enough, our modern era is in some ways more regressive than, say, 1959. Althought the 1950s weren’t known for their progressive portrayals of Asian Americans in Western films, in that year Asian men appeared as objects of desire in two significant movies. In 1959 the Hawai’ian born Sansei actor James Shigeta made his big-screen debut in Sam Fuller’s film The Crimson Kimono, playing a Los Angeles detective assigned to the case of a murder of an exotic dancer. The film is an engaging cop movie but it’s most notable for its portrayal of a love triangle involving Shigeta, his white partner Sgt. Charlie Bancroft, and Bancroft’s girlfriend Christina, who is also white. Unlike most such romantic conflicts involving an Asian man opposite a white guy, in this case Shigeta got the girl, which made The Crimson Kimono a groundbreaking anomaly in Hollywood. James Shigeta was a co-winner of the 1960 Golden Globe Award for Most Promising Male Newcomer and he would go on to a moderately successful career as a romantic lead for a few years but he never became the superstar that his good looks and charisma would indicate. Like most Asian American men in Hollywood up until and after that time Shigeta ran into the impenetrable glass ceiling of racism.

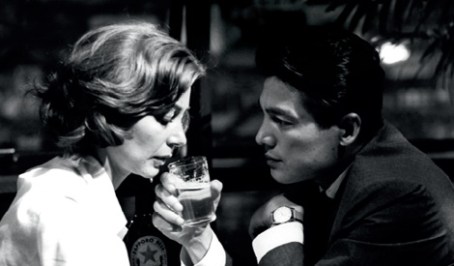

1959 also saw the depiction of another desirable Asian male, in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour. In that film Eiji Okada plays the intensely romantic Lui, a Japanese architect who has a brief and torrid affair with a Frenchwoman played by Emmanuelle Riva (seen most recently in Michael Haneke’s Amour). With a screenplay by noted Asiaphile Marguerite Duras (L’Amant/The Lover; Un barrage contre le Pacifique/The Sea Wall), Resnais’ film depicts Lui as suave, tender, and desirable, which contrasts greatly with the ways that Hollywood has typically portrayed Asian men. Okada is particularly swoonworthy as he and Riva’s character passionately discuss love, war, genocide, and beauty, against the backdrop of the site of first the atomic bomb attack. With the ruins of Genbaku Dome in the background, the film also utilizes a nonlinear narrative structure that links the European front, as exemplified by a long flashback set in France, to the Pacific theater, with Hiroshima repping for all of Japan. Set some fifteen years after the end of World War II, the film emphasizes the human cost of the war even many years after its ceasefire, as both Lui and Elle have been scarred by the loss of loved ones in the conflict. Elle fetishizes both her late German lover and Lui, as she is drawn to them due to their difference and otherness.

Now releasing theatrically for the first time in years in a new 4K digital restoration, Hiroshima Mon Amour remains fresh and relevant both thematically and stylistically (it’s regarded as one of the most influential films of the early Nouvelle Vague, or the French New Wave). It’s also an example of an early representation of an Asian male as not a caricature, a villain, or a clown, but as a fully fleshed out, highly desirable romantic lead. Now if only Hollywood could get a clue and do the same in the 21st century.

Opens October 31

3290 Sacramento St.

San Francisco CA

(415) 346-2228

Career opportunities: 7 Boxes movie review

So this weekend I sat through the four-hour-plus Oscar ordeal since my kids wanted to see the pretty people all dressed up and as usual I felt like I’d eaten six boxes of transfat Oreos afterwards, i.e., not good. Although it was nice to see Les Blank get a shoutout and to see the words “documentary filmmaker” up on the screen, the moments of interest to me were few and far between—those included the two technical nominations for Wong Kar-Wai’s The Grandmaster (Harvey Weinstein works it, right?), the Best Foreign Film nomination for Rithy Pran’s harrowing personal doc, The Missing Picture, and pinoy Robert Lopez winning an Oscar for Best Song and becoming the first Asian American member of the EGOT club. Although there were actually some African American presenters in the sea of whiteness, once I realized that Brad Pitt was one of the producers of 12 Years A Slave, its Best Picture win all made sense to me.

After witnessing this onslaught of self-congratulatory narcissism I needed an Oscar antidote in a bad way. Luckily the show ended at 9p PST so I still had time to scrub out my brain, and a great little indie crime film from Paraguay, 7 Boxes (7 Cajas), just about did the trick. Although it closely follows a bunch of crime film conventions, compared to most Hollywood bloat its stripped-down aesthetic was like a breath of fresh air. Shot on digital in one location over two nights, the film has no car chases, no stars, no glamor, and precious little digital effects (except for some speed-ramping and a bit of neon color correction). This is not to say that the film is in any way naïve or primitivist—veteran Paraguayan directors Juan Carlos Maneglia & Tana Schemboribut know their way around a camera and their cinematic style includes a whole lot of wit, smarts and panache.

The plot involves Victor, a young dude who makes his living hiring out his wheelbarrow (more like an oversized flatbed handcart) to various customers of Mercado Cuatro, a large outdoor market in Asunción, Paraguay. Victor wants to be a tele star and he becomes entranced by a video cell phone that his sister is selling second-hand for a pregnant co-worker who’s short of cash. In order to purchase said electronic device Victor takes on a job from a questionable meat-market employee who promises him a hundred dollars US if he can deliver seven boxes to a to-be-determined location elsewhere in the market. The film follows Victor’s misadventures as he attempts to navigate his precious cargo through the overstuffed mercado, running afoul of various criminal plots and activities as he realizes that the seven boxes may be more trouble than they’re worth.

The film is in no way groundbreaking in its subject matter but I believe it’s use of wheelbarrows as getaway vehicles might be a cinematic first, and the movie is a tightly constructed, clever-as-all-hell variation on the crime genre. Celso Franco as Victor anchors the cast with an unpretentious performance and the script is droll and amusing, with the Spanish and Guarani slang peppering the dialog adding to the film’s street-smart atmosphere.

Directors Maneglia and Schemboribut make great use of the Mercado, both as a crowded daytime destination as well as a deserted nighttime locale. Their background in short film and music video production contribute mightily to the film’s snappy pace and economical storytelling and keep the proceedings moving along briskly. The movie makes some passing commentary about the allure of media culture, the oppressive banality of working life, and the ineptitude of both police and thieves, but the film by no means focuses on social issues or Paraguay’s plight as a developing country. Rather, the movie is a great little caper film and a refreshing change of pace from the overwrought self-importance of multimillion dollar Hollywood product.

7 Boxes

Co-directed by Juan Carlos Maneglia & Tana Schembori

Opens February 28, 2014

3117 16th Street

San Francisco, CA

Family Affair: Like Father Like Son movie review

Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s newest film, Like Father Like Son, opens in San Francisco this weekend and it’s an outstanding example of a simple premise explored with utmost sensitivity and sincerity. The story is straightforward—two families discover their respective 6-year-old sons were swapped at birth at the hospital. They then must decide if they are going to trade the children back to their biological parents or continue to raise the sons who are not their blood relations. The film follows the effects of this momentous decision and the impact it has on each family.

Like a fine line drawing, the narrative reveals itself with subtlety and precision and is delivered with a light, understated touch that complements the underlying depth of emotion. What’s unspoken is as significant as what is said, and there’s not an ounce of fat on the exposition. By presenting only the most significant information the film focuses on the great importance of a casual remark or a banal gesture.

Kore-Eda’s naturalistic direction elicits beautiful performances from the kids as well as the adults, and he never allows their performances to devolve into cheap emotionalism. The characters are fully fleshed out, and every action and reaction feels true and genuine. Kore-Eda also manages to draw out a remarkable amount of tension from the plotline which on the surface seems almost too pat and simplistic. Yet the story goes to the heart of one of the humankind’s strongest bonds and explores the relationship between parent and child, questioning whether blood ties mean more than an adoptive family’s affection. In popular culture family ties all too often come off as false or exaggerated, so it’s to the director’s credit that he manages to infuse his characters’ interrelations with great meaning and significance and that he’s able to clearly communicate the heartbreak of their actions without reverting to sentimentality. At no moment does the film lapse into melodrama, although it easily could.

This is remarkably delicate and sensitive filmmaking, without a trace of bombast. The cinematic rendering of the narrative is poetic and lovely, almost minimalist in the way that character and plot details are revealed, yet it never loses its deeply felt connection to the characters’ humanity. It’s one of the best family dramas I’ve seen in a while and it’s highly recommended.

opens Friday, February 14, 2014

Landmark’s Opera Plaza Cinemas, 601 Van Ness, San Francisco (415)771-0183

Landmark’s Shattuck Cinemas, 2230 Shattuck Avenue, Berkeley (510) 644-2992

Spread Your Wings: More airplane movie film festival

Another round of international flights, this time on the much more updated Singapore Airlines. Not only does Singapore have a full 1000-plus slate of movies on demand but they have an entire Indian food menu to go with their Chinese and “Western” selections. Since they were out of the chicken mushroom rice noodles by the time they got to my seat, I ordered the chana daal, which came with lime pickle, some outstanding curried vegetables, a rather dry roti, and raita, which beats most U.S. airlines’ food service any day. Alas, they did not have the cup noodles featured on Cathay Pacific flights so my middle-of-the-flight hunger pangs had to be assuaged by a mediocre cold cheese sandwich. But lots of movies on tap!

Switch

This 2013 release was a sensation in China last year for all the wrong reasons as it was rated one of the worst movies ever on China’s online discussion forums, douban and baidu. The movie paradoxically was also one of the highest grossing films of the year in China, due to very bad word of mouth, and it indeed lives up to its negative hype. Truly unique and fascinatingly bad, it’s an astoundingly shoddy cinematic construction that plays like a bunch of fancy and expensive set pieces only tentatively linked together by a narrative structure. Genial superstar Andy Lau Tak-Wah portrays a super-spy assigned to crack the case of an arcane art heist involving two halves of a lengendary scroll painting. Along the way the film throws in a quartet of girl assassins on roller skates in clear plastic miniskirts, an obligatory psycho Japanese villain, and many gratuitous Andy-lounging-on-the-beach-in-Dubai shots, as well as fancy aerial shots of a car flying through the air dangling from a helicoptor attached to a magnetic grappler, a surfeit of swordfighting, explosives, and incendiaries, and many, many costume changes. The movie is full of technology fetishism at its best, and Andy Lau gets to be a combination of James Bond and a low-rent Tony Stark, complete with transparent floating holographic computer readouts and ridiculous gadgets. With its illogical leaps in time and space, the movie is great if you think of it either as one long dream sequence or as one long Andy Lau watch commercial.

Red 2 (Lee Byung-Hyun parts only)

Because I was fortunate enough to watch this on a plane I could skip over all but the scenes involving Lee Byung-Hyun, which absolutely elevated my viewing experience. In this one LBH demonstrates his much improved English diction and gets to play out a greatest-hits of Asian male action tropes. In his introductory scene he appears buffed out and naked, back and front, then goes on to assassinate someone with origami while wearing a kimono. Along the way he also brandishes two guns at time in a shootout, displays some high-kicking hung fu, and, in a pretty fun car-chase/shootout, practices a bit of Tokyo-drifting with a gun-toting Helen Mirren. As per usual LBH looks sharp in a tailored suit and holds his own as he grimaces and swaggers with John Malkovich and Bruce Willis. Somehow the audio on my seat-back monitor got switched to Japanese in the last five minutes of the movie so I missed out on all of the banter in the denouement, but I’m sure it was awesome and clever, and it was actually kinda fun seeing Helen Mirren dubbed in Japanese. In my fangirl dreams she and LBH have a thing for each other—spinoff sequel?

English Vinglish

I LOVED THIS MOVIE. The best thing I’ve seen in a long time, English Vinglish is a lovely family dramedy anchored by Sridevi’s charming performance as a woman trying to balance between duty and self-worth. Sridevi is brilliant as a beleagured Mumbai mom and housewife who comes into her own on an overseas trip to New York City by herself. I probably also liked it since the main character is a mother on a long trip away from her family, which, seeing as I was on a long trip away from my family, made me feel all sympathetic and stuff. Also, Sridevi wears some of the most excellent floral-print saris I’ve ever seen.

Fukrey

Another winner and another example of the resurgence of commercial Hindi-language cinema (aka Bollywood), Fukrey (“slacker”) is a bit like The Hangover, B’wood-stylee. The plot involves a quartet of Dehli townies who long to attend the local college despite their apparent lack of intellectual gifts. Among those aspiring students are Coocha and Hunny, a pair of cheerful losers who earn their living as dancers in costumed street productions of religious Hindu mythologicals, and who apparently have a foolproof way of predicting winning lottery numbers that involves arcane dream interpretation. Their interplay in particular includes some extremely funny comic moments and the two riff off of each other as deftly as Martin and Lewis. Dreamy musician Zafar is stuck in a rut—three years after graduating college he’s still fruitlessly pursuing his musical aspirations, which causes his sensible and levelheaded girlfriend, who also teaches at said college, no end to angst. Lali works at his dad’s popular restaurant and sweet shop and also aspires to attend the local college, though he currently can only take correspondence courses. Somehow the four protagonists get caught up in an increasingly tangled morass of financial woe, eventually ending up in debt to the tune of 2.5 million rupees to the local drug boss, a toughie named Biphal (the excellent Richa Chadda from Gangs of Wasseypur 1 & 2) who has “Sinderella” tattooed on the back of her neck. The plot twists and turns ala its spiritual predeccesor, the equally clever and irreverent Delhi Belly, making great use of that city’s crowded, dusty locale to accentuate the characters’ sticky situation. The comedy is deft and skillful and, despite many chances for overdoing it, director Mrighdeep Singh Lamba directs with a fairly understated hand. The characters are somewhat broadly drawn at first but become complex and sympathetic and Lamba has excellent and economic visual storytelling skills—his narrative structure and editing cleverly tie together all of the loose ends of the wide-ranging story. This is the best kind of movie to watch on a long plane flight, with a nice long running time that eats up hours, a fun, lighthearted romp of a story, and amusing and likeable characters. Throw in a few quick episodes of song and dance and you have a winner. Great stuff—

Vishwaroopam

An outstanding Tamil-language spy film written and directed by and starring the amazing Kamal Hasan. This is only the second Tamil film I’ve seen (the first having been Puddhupettai, starring the wonderful Danoush,) but it definitely won’t be my last. The film starts off in New York City as an upwardly mobile NRI woman (Pooja Kumar) describes her marital issues to her sympathetic psychologist. Somehow, through a series of complicated and indescribable narrative turns, the film ends up in the middle of an Al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, where the plot takes a lengthy digression. The story then wends its way back to New York to further explicate links between Al-Quada terrorists, uranium, an oncology lab, and radioactive pigeons. A bomb scare and much frenetic action follows. Lead actor and director Hasan, who gets to show off his hand-to-hand martial arts chops as well as his classical Indian dancing skilz, among many other talents, anchors the film with his charismatic performance as the super-spy with a complicated personal life who wryly notes, “I have a lot of emotional baggage.” The movie’s production values are top-notch, the songs by Shankar, Ehsaan and Loy are outstanding, and the war scenes pull no punches, with men, women and children blown up, shot, strafed, and otherwise becoming collateral damage in the vicious guerilla fighting. The only weak link is Kumar as the clueless wife—she’s not quite able to pull of her character with much conviction, though admittedly she’s not given a lot of to work with.

Ip Man: The Final Fight

I only got to watch the first five minutes of the latest installment in the ongoing Ip Man saga before the in-flight movie system on the plane was shut off. This chapter, directed by stalwart Hong Kong director Herman Lau, chronologically follows the unrelated Donnie Yen pair of Ip Man movies as well as the unrelated Wong Kar-Wai version, The Grandmaster. Yau did direct Ip Man: The Legend Is Born, the prequel starring Dennis To as baby Ip Man, so there might be some thematic continuity there but for the most part the Ips are all running in parallel universes. Since the flight attendants had already confiscated the headphones by the time I started watching the movie it was a silent viewing experience for me, but I did get to see a very nicely staged encounter in which Ip Man challenges an eager young disciple to a battle to knock the grandmaster off of a square of newspaper laid on a kitchen floor. I watched the rest of the movie a few weeks later after I got back home and it didn’t disappoint, as a fun little slice of bygone Hong Kong ala Echoes of the Rainbow. Anthony Wong is great as the middle-aged Ip Man, carrying himself with dignity, grace, and the inimitable Wong Chau-sang swagga. The movie also includes familiar Hong Kong cinema faces including Anita Yuen as Mrs. Ip, Eric Tsang as a rival martial arts master (who has an outstanding duel with Ip Man that’s a marvel of cinematic fight choreography in the way that it makes two non-martial artists look incredibly suave and skilled), and Jordan Chan and Gillian Chung (yes, that Gillian Chung) as a couple of Ip Man’s disciples. In the face of the continued encroachment of China’s commercial film industry on the Hong Kong moviemaking world, it’s nice to see a genuine HK film with actual Cantonese dialogue (albeit with Ip Man and Mrs. Ip feigning broad Foshan accents). Bonus points for Anthony Wong not being afraid to play an old, albeit very cool, dude.

Rumour Has It: Caught In The Web movie review

Although local multiplexes and arthouses are stuffed to the gills with prestige Hollywood Oscar-bait at this time of year, for some reason there are also three new films by top Chinese directors opening this weekend in San Francisco. Bay Area Asian cinephiles can thus take a break from furry-footed halflings, lost-in-space astronauts, and ironic 1970s flashback films.

Chen Kaige’s Caught In The Web looks at the corrosive power of gossip, fueled by the virality of the internet. Gao Yuan Yuan stars as Ye Lanqiu, a woman who’s just received a terminal cancer diagnosis. Riding home on a city bus she sits in a daze, oblivious to the bus conductor chivvying her to give up her seat to an elderly man. As is per usual in this modern world, the encounter is recorded via cameraphone and uploaded to the web by an ambitious young Internet journalist, with the assistance of her hits-happy editor, who salivates with the prospect of posting a trending topic to her online news site. The video goes viral, with an ensuing outcry from China’s netizens, and Ye, dubbed “Sunglasses Girl” by nosy web-dwellers, soon becomes the target of a hyperaccelerated storm of controversy, with her life and character minutely scrutinized and critiqued.

With 600 million registered users and 60 million active users per day on weibo, the Chinese version of twitter, China has a ridiculously busy online culture and the film cleverly indicts the hearsay, rumor, and conjecture spawned by that culture and the lightning-speed with which a person’s name can be dragged through the mud. By focusing on the interweb’s vicious gang mentality Chen, the director of Farewell, My Concubine, (one of the seminal critiques of Mao’s China), also obliquely references the Cultural Revolution’s practice of betrayals and outings and the rapidity with which lives can be destroyed and reputations ruined based on politics, whim, and speculation. Chen also takes aim at China’s nouveau riche, as Ye’s boss Shen Liushu, a corporate oligarch, is a bossy patriarch who lords his financial dominance over his conspicuously consuming wife. Chen Ruoxi, the Internet news editor, (played by Yao Chen, in real life aka the Queen of weibo) mirrors Shen’s arrogant ruthlessness as she estimates page hits and site visits while disregarding the human cost of her calculations.

Though it bogs down a bit in the second half with some treacly stuff about finding meaning in life while you can etc, it’s a pretty lively little flick that shows a reinvigorated Chen Kaige in good form. With 2012’s pretty-but-stilted historical drama Sacrifice it seemed like Chen was stuck in a rut, but Caught In The Web shows that he’s still got something to say, and can say it in a brisk, contemporary style. His social critique is as trenchant as when he made Farewell, My Concubine (1993) and Yellow Earth (1984) and he’s adapted his filmmaking style to match the up-to-the-minute subject matter—the film’s rapid-fire editing suits the amped-up topic as each scene is cut with overlapping sound, jump cuts and truncated dialogue that echoes the hyperfueled activity of the internet.

Also opening this weekend in SF are two other new films by well-regarded Chinese directors. The Roxie Theater screens A Touch of Sin by Jia Zhangke (Platform; Still Life) which got a five-star review from the NY Times and which intertwines four stories of contemporary China in a bleak allegory about the disintegration of human interconnectedness. Playing at the AMC Metreon, Personal Tailor, probably the most commercial of the three films from China opening this week, is directed by Feng Xiaogang (If You Are The One; Back to 1942; Aftershock), which means that despite its seemingly lighthearted topic about a company that brings its clients’ fantasies to life, it’s likely full of veiled social critique. It also stars the brilliant Ge You (Let The Bullets Fly), which is always a plus.

Caught In The Web opens Friday, January 3, 2014

Landmark’s Opera Plaza Cinemas, 601 Van Ness, San Francisco (415)771-0183

Landmark’s Shattuck Cinemas, 2230 Shattuck Avenue, Berkeley (510) 644-2992

Sky Pilot: Airplane movie film festival, aka back-of-the-seat insommia filler

So I got on the plane from Frankfurt to SFO on Sunday and I was horrified to discover that there were no back-of-the-seat individual video screens on the flight. I could not remember the last time I was on a flight longer than an hour without personal video service and since I was staring an 11-hour transatlantic flight in the face, I was pretty pissed off at myself for booking on United Airlines, which is apparently so impoverished that it can’t afford to upgrade its fleet to 21st century standards. That bit of first-world bitching aside, I started to think about the many films I’ve seen lately on those tiny little embedded monitors, so herewith follows the first in an irregularly scheduled series of reviews from the airplane movie film festival. All details from a haze of jet lag, leg cramps, and crappy airplane food.

The Great Gatsby: a fun and spectacular adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic book, this one by the reliably lurid Baz Lurhmann, who transformed the book into a video game complete with swooping camerawork, hiphop, and Leo DeCaprio brooding as the titular character. Toby Maguire not in a spidey-suit is good as Nick Carraway, the Jazz Age babe in the woods. Another little surprise was Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan in a small role as a Jewish bootlegger (since apparently Indian is the new Oriental). I haven’t read Fitzgerald’s book (what?) and I have no allegiance to its plot particulars so I enjoyed the movie as a standalone piece, with the Jay-Z soundtrack and anachronistic mylar party streamers adding to the shiny fun.

The Silent War: Tony Leung Chiu-wai as a blind guy helping the military crack codes in 1949 China. I either missed the plot point or it was never clarified as to whether Tony was helping out the Communists or the Nationalists, and I missed the last twenty minutes of the movie due to starting the film too late (a recurring error on my part), but the art direction was pretty authentically period and Tony and Zhou Xun, who plays a sleek Chinese spy, both acquit themselves pretty well. My movie-viewing experience probably suffered from seeing the film on a tiny digital screen, so if I get the chance I’ll watch it again to get the full effect of the nice cinematography and slick 1940s costume design, since I love the look of peplum skirts, finger rolls, and tweed coats.

Star Trek: Into Darkness. A dumb and dreadful followup to the excellent Star Trek reboot from a few years back that features a very Anglo Benedict Cumberbatch as Khan, which is weird since the character was memorably portrayed in previous incarnations by Mexico-born Spaniard Ricardo Montalban. Cumberbatch is properly menacing and he bellows in his best Shakespearean actor mode, but since Montalban’s archetypal Khan is permanently etched in my brain, Benny’s blue peepers and pale skin threw me off. Zachary Quinto continues his excellent vocal mimicry of Leonard Nimoy (who gets a brief cameo, looking very aged) and Chris Pine grimaces as young Captain Kirk. British actress Alice Eve is good as Dr. Carol Wallace, but her character’s braininess doesn’t preclude her a fan-service scene in her underwear. As a busty blonde she also has a passing resemblance to her TOS predecessor, Yeoman Janice Rand, which means that she & Capt. Kirk will probably get busy some time in future installments. Zoe Saltana as Lt. Uhura mostly exists to be the emotional proxy for the stoic manly men in the movie since every time a crisis comes up the movie cuts to her looking shocked or sad.

Iron Man 3: another film viewing tragically cut short due to my inept movie-watching time management. Robert Downey Jr. swaggers and smirks and Gwyneth Paltrow takes up space, and I suspect one’s enjoyment of the film is directly related to how much you like RDJ’s schtick. He’s a really good actor but I’m having trouble remembering the last non-Iron Man movie I’ve seen him in lately (Zodiac? Sherlock Holmes?). I wanted to see the end of the movie to find out more about The Mandarin, the neo-Orientalist character here presented as a middle eastern/western Asian character by half-desi actor Ben Kingsley. But alas my seatback screen went haywire halfway into the movie and I couldn’t get it to work in time to watch the whole thing. So I took a nap instead.

A Werewolf Boy: a charming little South Korean fable about a girl and her lycanthrope, here played with shaggy-haired K-pop charm by Song Joong-ki. This movie was one of the top grossing films in S. Korea last year so, although teen romances aren’t usually my thing, I wanted to check it out to get a sense of the South Korean pop culture gestalt. Although it’s supposed to be set “forty years ago,” around the 1970s, there were some glaring anachronisms in the art direction and costuming, but despite its shoddy mise-en-scene the movie was a fun little timepass. This is the second wolf-girl teen romance movie from Asia that I’ve seen recently, the other being Mamoru Hosoda’s animated movie Wolf Children, so I’m thinking—are werewolves the new vampires? Or if I want to put a cultural studies frame around it, what do the popularity of these films say about the ongoing transnational hybridity of Asian identities? Sorry, been writing a lot of academic proposals lately so my mind is locked in theoryspeak.

Gangsta’s Paradise: On The Job movie review

The international film world is a trendy place, and programmers are constantly mining national cinemas for the next big thing. Among Asian countries, in recent years Hong Kong, South Korea, and Thailand have became the source for hot and happening directors such as Johnny To, Kim Ki-Duk, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and more, as film fests try to scoop the latest and hottest genre and arthouse directors to liven up their programming. This year’s flavor seems to be the Philippines, as four new Filipino films premiered at Cannes this year. I call it the “Brillante Mendoza effect,” since that director has had a run of movies screening at tony international film fests like Toronto, Hong Kong, and Cannes, where Kinatay famously and controversially won the Best Director prize, after which Roger Ebert declared it was “the worst film in the history of the Cannes Film Festival.” Filipino movies have started to get more respect in Asia as well where, interestingly enough, they are often disregarded or ignored by their more established cousin industries in Hong Kong, Japan, and China. Veteran actors Nora Aunor and Eddie Garcia both won acting awards at the 7th Asian Film Awards in Hong Kong this year, and also won big at the Asia Pacific Film Festival in Macau and the Asia Pacific Screen Awards in Brisbane, Australia. So much like sisig and adobo are the food truck flavors of the month, Filipino cinema has become the new darling of international film set.

Erik Matti’s On The Job was one of the Filipino Four that screened at the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes this year and in the past few years his work has been popping up at festivals in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. Unlike Mendoza, his arthouse countryman, Matti’s a longtime veteran of Filipino commercial film and television production, starting out directing adverts for Filipino TV and moving on to direct a slew of genre product including horror, crime, and comedies.

A gritty, entertaining crime thriller, On The Job was produced for commercial distribution in the Philippines, not for international arthouse audiences, but Matti’s confident control of the material elevates the film from a mainstream genre picture to something more.

The movie opens with a no-nonsense sequence showing Tatang and Daniel, a pair of sketchy dudes, shooting down a man execution-style in broad daylight in a crowded street. Despite their faces being fully exposed the two killers are fearless, seemingly unconcerned about witnesses or the possibility of arrest. It soon becomes clear why they can stroll the streets murdering people—right after they do the deed they’re taken off to prison, where they’ve been residing as convicts for years, hiding in plain sight while the police search fruitlessly for them.

On the case is Senior Detective Acosta, a veteran cop, paired up with Atty. Francis Coronel, an up-and-coming young federal investigator whose father-in-law is a big-time politician. Acosta and Coronel’s relationship parallels that of Tatang and Daniel, drawing classic genre connections between cops and criminals.

On The Job plays up the corruption of the PI police and politicians and their links to their shadow partners, the criminals doing the dirty work of assassinations. Matti’s film boasts a strong premise, hyperkinetic roving handheld camerawork, great sound design, and smoky filtered lighting, with bursts of violence punctuating the narrative. Matti draws out strong performances from his cast, which includes heartthrob Piolo Pascual as Coronel, the upstanding young federale who falls into a pit of corruption once he starts investigating the case. Despite being very pretty, Pascual is believable as a driven and determined investigator whose family connections are a dubious benefit. Anchoring the film is veteran Filipino actor Joel Torre as Tatang, the middle-aged convict/killer who’s hoping to escape his shitty life situation by taking on contract assassinations.

What’s missing is a sense of exactly why Daniel, the younger convict, would willingly become a coldblooded assassin. Tatang, the older of the pair of cons, has a full backstory complete with a two-timing wife and a daughter he’s putting through college, but Daniel’s life is a bit sketchy. It’s not until more than halfway into the movie that we see evidence of a girlfriend or any other positive interpersonal relationships besides his friendship with Tatang. I get that he’s in prison and this might be a way to gain his freedom, but he doesn’t seem to feel a lot of remorse for the ruthless murders he commits. The movie doesn’t effectively reveal how the Daniel started out or where he’s going, only where he is right in the moment. This robs the film of some emotional impact beyond the visceral repulsion of his violent killings. However, his relationship with Tatang, his mentor-in-crime, is strongly developed and its ultimate conclusion is powerful and unexpected, yet logical in the scheme of the characters’ dynamic.

On The Job opens this weekend across the U.S. and has a chance to be a breakout Asian film in both arthouse and mainstream cinemas. Because of the genre’s enduring popularity and accessibility, crime films like OTJ have become the lingua franca in the international film world, and Matti may be the latest Asian director to cash in on the ongoing crime film wave.

Opens September 27

AMC Metreon in San Francisco

Century Tanforan 20 in San Bruno

Milpitas Great Mall in Milpitas

Union City 25 in Union City

Century 14 in Vallejo

Don’t Take Your Guns To Town: Drug War film review

A new Johnnie To joint in U.S. movie theaters is an event to be celebrated and this month sees the stateside release of Drug War, To’s latest crime film. The prolific Hong Kong filmmaker has directed more than fifty movies since the 1980s and in the past ten or twelve years or so he’s become an international film festival darling, but only about a dozen of his movies have seen theatrical releases in the U.S. (the last being Vengeance in 2009). Drug War is his first crime film set in mainland China (his first ever was last year’s rom-com Romancing In Thin Air) and while it may look and feel very different from his earlier Hong Kong-based classics, in its subtle challenges to the status quo in the Chinese film industry Drug War demonstrates that To and his Milkyway Image production house are still creatively shaking things up.

The plot involves Timmy Choi (Louis Koo), a Hong Kong drug manufacturer working in China who is summarily busted in the film’s opening sequence. In order to save his skin and escape the death penalty under China’s draconian anti-drug laws, Choi agrees to aid a crew of mainland cops, lead by Zhang Lei (Sun Honglei), in organizing a sting against his compatriots. The film then follows the uneasy alliance of Choi and Zhang as they trace Choi’s fellow drug-runners up the supply chain.

Drug War is in some ways a much more a standard policier than your usual To movie. Soi Cheang (Motorway; Accident) is credited as a second unit director and might have had a hand in shaping the look of the film, but the change in milieu from To’s usual Hong Kong stomping grounds to mainland China might also account for the difference in the film’s visual texture. The movie is shot in a predominantly blue palette with mostly natural lighting that feels more Ringo Lam-like than Milkywayesque. To also uses the wide-open, smoggy spaces of industrial China and its endless six-lane highways and anonymous cities as metaphors for the blurry ethical and moral road his characters travel down.

Nowhere to be found is the surreal high-gloss sheen of To’s earlier Hong Kong-based crime films such as Exiled, Election, or PTU, which were gorgeous visual paeans to the beauty and decadence of the former Crown Colony’s criminal societies. The grit coating the economy cars and paneled trucks cruising along Drug War’s Chinese roadways contrast starkly with the glossy sleekness of the luxury vehicles speeding down the roads of nocturnal Hong Kong in Milkyway classics like The Mission. Even the perpetually glamorous and handsome Louis Koo is scuffed up, his famously tanned, square-jawed visage occluded by scabs, burns, and an unsightly white bandage across the bridge of his elegant nose.

The film also displays little of To’s previous quirkiness, possibly reflecting the reduced influence of long-time collaborator Wai Ka-Fei or the recent death of longtime Milkyway screenwriter Kam-Yeun Szeto. Although there’s some submerged humor in the spectacle of a couple coke-addled flunkies driving endlessly through the vast Chinese landscape, as well as in the inclusion of a pair of deaf-mute brothers who man a drug manufacturing plant, for the most part the movie plays it pretty straight.

There’s also much less action than in To’s previous work, but when the guns do come out the excellent shootouts demonstrate To’s easy mastery of the action genre. This is especially notable in a brief yet effective gun-battle inside a drug manufacturing plant that escalates from handguns to rifles to explosives with military precision. The film’s climactic showdown recalls the ending of Expect The Unexpected (1998), nominally directed by Patrick Yau but most likely ghost-directed by To, in which a shootout leads to bloody and indeed unexpected results.

Sun Honglei shows some range as the stoic Mainland cop who once undercover transforms into a jovial drug dealer, but in contrast to the naturalistic tone of most of the movie his performance skates dangerously close to hamminess. Louis Koo is somewhat wooden as the enigmatic Timmy Choi but this is possibly appropriate, since he’s portraying a man with a lot to hide. When Choi mourns his recently deceased wife, however, Koo’s performance lacks the pathos and depth of emotion that a more skilled thespian such as Francis Ng or Lau Ching Wan might have brought to the scene. Interestingly, the most engaging supporting characters are the seven Hong Kong character actors, including Milkyway stalwarts Lam Suet, Michelle Ye, and Gordon Lam, who make cameo appearances as drug dealers in the second half of the film. This perhaps unconsciously reflects To’s comfort zone in dealing with Hong Kong performers vs. the less familiar mainland actors.

Though Drug War may not be quite as fabulous or fully realized as some of his earlier classics it’s an entirely respectable and watchable product that has a certain grim integrity. The film is one of the first that To’s made while working under SARFT (State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television), China’s infamous censorship board, yet despite the censor’s approval To manages to infuse the film with a complexity of morality not found in many commercial Chinese films. Both cops and criminals are ruthless, amoral, and obsessed, using any means necessary to achieve their respective goals, and all meet similar fates in the end. The most interesting supporting characters are the aforementioned Hong Kong criminals as well as the deaf-mute drug manufacturers who, along with Louis Koo’s Timmy Choi, are the only characters with visible family ties. In contrast, aside from Sun Honglei as Zhang and Crystal Huang as a female detective, the mainland cops blend together in an anonymous blur. Some observers claim that the film is a parable for the fraught state of Hong Kong-China relations and To himself has spoken of the way in which he used the film as an experiment to see how far he could go in transplanting his Hong Kong-style crime movies to the mainland. If To in one of his first mainland productions has managed to sneak in some sociological critique under the noses of censors and push the envelope of acceptability under SARFT regulations then that bodes well for his fortunes in China. In the future it will be interesting to see how he copes with the strictures of working on the mainland and if he can maintain his vision and aesthetic despite SARFT’s watchful eye.

Many thanks to Ross Chen, Kevin Ma, Sanney Leung, Chuck Stephens, and Shelly Kraicer for their imput and assistance in this piece, especially their vital insights into Johnnie To’s clever subversions of SARFT restrictions.

Drug War North America showtimes

Recent Comments