Posts filed under ‘Uncategorized’

Fun With Ropes: Saving Mr. Wu movie review

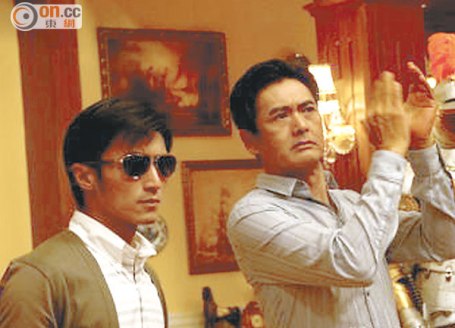

Andy Lau’s latest mainland China vehicle, Saving Mr. Wu, released in the U.S. this weekend with not a lot of fanfare. As far as I can tell it’s the first stateside release from United Entertainment Partners, one of China’s big distribution entities. As noted in the Hollywood Reporter in June 2015, “UEP touts itself as the number-one movie distribution network in China, with the company claiming it covers 90 percent of major cinemas in the country.” That same article noted that longtime Sony executive Steve Bruno joined UEP in June to lead its North America division, which will bring Chinese films to the U.S. and Hollywood films to China. Saving Mr. Wu is its maiden voyage into the North American movie market.

Saving Mr. Wu is a fast-paced, hard-boiled piece of crime filmmaking, with director Ding Sheng, who also serves as witer and editor, moving things along at a rapid clip. The pacing is similar in many ways to classic Hong Kong crime films, with very quick edits and terse dialog interspersed with bursts of action. The film’s cinematography is also evocative, depicting a mostly nighttime 21st century Beijing full of wide boulevards, high-rises buildings, and sleek automobiles.

The film is based on the real-life 2004 kidnapping of well-known Chinese television actor Wu Ruofu (who plays a supporting character in the film), with Andy Lau in the title role. Andy basically plays a fictionalized version of himself, and as such he’s very good at it. Unlike his recent role in Lost and Love, where he played a farmer, here he doesn’t have to hide his preternatural good looks, the fine tailoring of his clothes, or his $500 haircut, which is totally fine. Andy’s real life superstardom also makes the reverence some of the kidnappers exhibit towards him seem genuine, and when he croons a song to comfort his fellow kidnappee, a mournful sad sack who exists mostly to be the kidnappers’ punching bag, the rendition is heartfelt and understated. Wang Qinyuan is also effective as the kidnapping mastermind Zhang, a sneaky sociopath who dreams of a big heist that will lift him out of his petty criminalism. Liu Ye plays against his usual saintly and righteous type (one of his roles was playing a young Mao Zedong in the 2011 propaganda extravaganza Founding of a Party) and manages a bit of swagger as the lead cop on the case. Also excellent is Lam Suet as Mr. Wu’s trusted friend from Wu’s days in the military. Lam makes the most of his considerable bulk and his legacy of menace from many Hong Kong gangster roles to evoke a hard-ass, no-bullshit attitude.

Interestingly enough, unlike many movies that have to run the gauntlet of the PRC’s SAPPRFT censorship boards, the film gestures towards social critique. When Mr. Wu asks Zhang why he leads a life of crime, Zhang replies that the system in China is stacked toward the rich and powerful and that because of cronyism, ordinary joes like himself never have a fighting chance. Later in the film Mr. Wu acknowledges that he owes a lot of his success to luck and good fortune, rather than simply hard work and talent. The film also suggests that such a brazen kidnapping, which takes place in the middle of a crowded nighttime street in Beijing, wouldn’t have been possible in Hong Kong, where there’s a more evident respect for the rule of law.

The film is a bit dense in the details, flashing back and forth across several different time frames, and at time director Ding seems unsure of the strength of his storytelling, most clearly seen in his reliance on unnecessary title cards to identify the many characters big and small who zip rapidly across the screen. But the movie as a whole is well-made, sleek, and tense, with a gritty, realistic feel. Like last year’s excellent Black Coal, Thin Ice, Saving Mr. Wu is another notable addition to the roster of recent film noirs coming out of the PRC.

Saving Mr. Wu

directed by Ding Sheng

AMC Metreon

Century Daly City

and other locations throughout North America

Shall We Talk: Coming Home and Office movie reviews

In an interesting coincidence, two famous Chinese-language film directors have films opening in the U.S. this weekend, but their respective movies might puzzle the casual viewer expecting a certain type of cinematic output from each director. But on closer inspection both movies are in some ways throwbacks to early periods of each director’s filmmaking careers.

Starting with Hero (2002) and continuing through House of Flying Daggers (2002), Curse of the Golden Flower (2006), and The Flowers Of War (2011), Zhang Yimou for the most part in the 21st century made a series of glossy commercial films that have been successful marketed in the West, and he capped off this run of box-office hits by overseeing the much-lauded opening ceremony for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. So viewers who only started following Zhang’s career in the 21st century might think that his oeuvre is all about wire-fu, movie stars, a hypersaturated color palette, and an affinity for spectacle. But Zhang started out in the 1980s as one of the so-called Fifth Generation of Chinese directors who were noted for their realistic styles and politically astute commentary. Often depicting the ordinary lives of peasants in China’s rural countryside and usually starring Gong Li, Zhang’s first several features were poetic ruminations on the effects on everyday people of various types of systematic repression. These movies, including Ju Dou, Red Sorghum, Raise the Red Lantern, and The Story of Qiu Ju, made Zhang the darling of the arthouse film festival set, so it was a bit of a surprise when he busted out with a string of martial-arts fantasies at the turn of the 21st century. But those later films were pretty big at the box office and thus many folks only know Zhang as a director of big-budget spectacles, so it might seem like a surprise that Zhang’s latest film, Coming Home, includes neither martial arts nor brightly colored costumes and sets. Astute observers, however, will realize that the movie actually harkens back to Zhang’s earlier Fifth Generation output from the 1980s and 90s.

Coming Home is a family drama set during and just after the Cultural Revolution in China and is based on the novel The Criminal Lu Yanshi by popular Chinese author Yan Geling (whose novella 13 Flowers of Nanjing was the basis of Zhang’s recent film The Flowers of War). The movie opens as former professor Lu Yanshi (Chen Daoming) surreptitiously arrives back at his town after escaping from a re-education camp. His devoted wife Feng Wanyu (Gong Li) attempts to meet him but is thwarted by the Chinese secret police and Lu is sent back to prison. Lu and Feng’s teenage daughter Dandan (Zhang Huiwen), an aspiring ballerina, resents her dad’s outlaw status since it’s messing with her career plans to play the lead soldier/dancer in the school play, which Zhang drolly depicts as leftist musical featuring dancers en pointe who are wielding rifles in the service of the revolution. Cut to several years later, after the end of the Cultural Revolution in the mid-70s. Lu again returns home but Feng has become addled from either a blow to the head, PTSD, early-onset Alzheimer’s, or a combination of all three, and thus doesn’t recognize him. The film then follows Lu’s attempts to reconcile with the amnesiac Feng.

Coming Home’s muted mis en scene at first seems a million miles away from the brightly colored, glossy sheen of Zhang’s martial arts movies but the film’s meticulous art direction, featuring scuffed walls, dull brick and wooden buildings, and threadbare wool coats and trousers, reflects Zhang’s careful attention to period detail and authenticity. The usually glamorous Gong Li tones down her customary high-wattage gorgeousness to play the dowdy teacher Feng, but in her performance she seems to have acting awards in mind, as she weeps piteously over Lu’s absence, then affects a glassy-eyed dolor to simulate mental confusion. (In fact, Gong was nominated for the first time for Best Actress for Taiwan’s 2014 Golden Horse award but lost out to Chen Shiang-chyi. In glorious diva fashion Gong subsequently pitched a fit, calling the Golden Horse unprofessional and vowing never to attend again.)

Although Gong is a bit off, Chen Daoming right on the money as the long-suffering Lu. His world-weary eyes and sorrowful demeanor speak volumes about Lu’s personal traumas and his experience becomes a metaphor for the human cost of China’s various social and political upheavals. Through Chen’s sensitive and understated performance the film becomes an allegory about the erasure of memory and the amnesia of the Cultural Revolution. In this way the movie hearkens back to director Zhang’s earlier films that focused on political and cultural critique, which preceded his more recent, more commercial output. Zhang also recently released another film set during the Cultural Revolution, Under The Hawthorne Tree, but his next project is the blockbuster Andy Lau-Matt Damon China/US-coproduction action fantasy The Great Wall. So he’s nothing if not versatile—

Also releasing in North America this weekend is the latest from Johnnie To, Office. Like Zhang’s movie, Office at first may seem like an anomaly in its director’s catalog but in fact the film, which is a musical comedy, has a lot in common with To’s past work. Though To is best known in the West for hardboiled crime movies like The Mission, Election, Exiled, and his last film, Drug War, he’s got a much more varied back-catalog than that. To got his start directing at Hong Kong’s television studio TVB and there he directed everything from romances to comedies to martial arts historicals, including the famous period drama The Yang Family Saga. His prolific filmmaking output includes the fantasy action films The Heroic Trio and The Executioners, the comedy farces The Eighth Happiness and The Fun, The Luck, The Tycoon, and Stephen Chow vehicles Justice, My Foot and The Mad Monk. Although his crime films have won him much love among Asian film fanpeople, To’s most commercially successful movies have been romcoms such as Needing You and Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart 1 & 2.

So it’s not as far-fetched as it might initially seem to be that Office is a musical, with all of its leads (except Chow Yun-Fat) singing at least one song in the film. The movie is a typical workplace drama infused with cogent commentary about the crisis of capitalism, The storyline follows two young acolytes at their first days on the job at Jones & Sun, a seemingly innocuous Hong Kong cosmetics company that’s actually in the throes of backstabbing and backroom deals. President Ho (Chow Yun-Fat) has a wife in a coma and Chinese investors knocking at his company’s door, while CEO Cheung Wai (Sylvia Chang) struggles to keep the company’s profits up and its products relevant. Salesman Wong Dawai (Eason Chan) is climbing the corporate ladder and is not averse to using personal relationships, including ones with CEO Cheung as well as fellow office drone Sophie (Tang Wei), in order to advance. Youngsters Kat (Tien Hsin) and Lee Xiang (Wang Ziyi) round out the ensemble.

But despite a stellar cast who admirably perform both acting and singing duties (with Cantopop superstar Eason Chan being the best and Tang Wei the worst among the vocalists), the real star of the show is the astounding art direction and set design by acclaimed veteran William Chang Suk Ping, who has won renown as the production and/or costume designer for innumerable classic Hong Kong films including In The Mood For Love, The Grandmaster, and Dragon Inn. Office was shot completely on a soundstage, with some outdoor scenes simulated via green screen, and Chang’s beautiful, stylized set dictates the mood of the film. Comprised mostly of brightly colored bars and rails, the set resembles a massive, skeletal architectural cage that encloses the action and the characters and lends a hermetically sealed, slightly claustrophobic feel to the film. The artificial staginess of the movie, with its simulated spaces and multiple levels of activity, recalls a Broadway musical more than a movie musical, with the set dominated by a huge, slowly revolving clockface. No pretense of realism is made in the film’s use of space, color, and structural elements, which adds to the knowing fakery of the movie’s design.

Despite To being the titular director, the film displays the strong influence of Sylvia Chang, who wrote and produced the film as well as playing the lead as CEO Cheung Wai, and who has an impressive resume as the director of films such as Tempting Heart (1999), 20 30 40 (2004), and Murmurs of the Heart (2014). Chang’s hand is clearly evident in the narrative’s complex personal relationships and its focus on the collateral damage of corporate machinations. To’s romcom background also comes the fore as the movie’s love hexangle recalls the similarly structured romantic entanglement in his 2014 movie Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart 2.

The weakest element of the movie’s musical conceit is its curious lack of interesting choreography. Despite taking place on a boldly designed stage set that cries out for equally bold movement through and across it, the movement during the musical numbers is surprisingly limited. The action during the songs in Office consists of mostly of synchronized head nods and a few characters walking in rhythm together. Office could stand to take a few lessons from Bollywood musicals, whose song and dance numbers fill every inch of the frame with dynamic, kinetic movement.

But all in all, the movie is a fascinating beast that promises to be brilliant up on the big screen. After first seeing in via online screener with tiny white subtitles I’m looking forward to watching it again in a movie theater where it belongs, and so should everyone, in my humble opinion.

dir. Zhang Yimou

opens Fri. Sept. 18

dir. Johnnie To

opens Fri. Sept, 18, 2015

The Show Stoppa: Kristina Wong’s The Wong Street Journal

I don’t know if I’ve ever met Kristina Wong face to face but she’s very present in my various newsfeeds. So as is often the case with 21st century social media relationships, at least in a facebook-friends kind of way it seems like I know her. Thus it’s only appropriate that her new solo show, The Wong Street Journal, opens with a quick discussion of her online presence and how its addictive quality has affected her life. Although eighty minutes isn’t all that long in the cosmic scheme of things, during the length of her performance Wong deftly illustrates the difference between superficial twitter wars and a thoughtful and intelligent discussion of various trigger topics like race, colonialism, white privilege and savior mentality, or what she dubs “nuance versus likes.” At the same time Wong is never didactic, preachy, or monotonous and skillfully keeps the show bubbling along at a fast and funny pace. Bursting at the seams with imagination and powered by Wong’s energetic performance, the show breaks down its subject matter with wit, humor, and intelligence.

Despite its title, the show doesn’t have a lot to do with the stock market—instead it’s an amusing travelogue to Northern Uganda, where Wong confronts her (yellow) savior complex and her honorary white person status. After a rapid introduction outlining Wong’s social media addiction and her lust for likes, the 80-minute show follows Wong as she travels to Africa for a quick artist’s residency at an NGO that gives micro-grants to women in the region. There she encounters underground hiphop producers, community activists, and the changing state of Uganda after its decade-long civil war. The story moves along rapidly, driven by Wong’s engaging and slightly neurotic but always self-aware persona as she comes to grips with her first-world privilege while inadvertently recording a rap album that later climbs the charts in Uganda.

Wong’s gift for lightly and intelligently dealing with hot-button topics like the tumultuous history of Northern Uganda and misperceptions of Africa as a region (which she outlines via the saga of celebrities adopting babies from various countries on the continent), makes The Wong Street Journal highly accessible yet continuously thought-provoking. Wong includes a brief but very useful explanation of white privilege for those who might need it, and which seems especially relevant post-Charleston, followed by the amusing revelation that in Uganda Wong is considered white.

She makes the most of her low-fi aesthetic, most prominently evidenced in the show’s fun and clever felt props and backdrops which include big red felt hashtags and a rolling scroll of felt scenery of Uganda complete with removable velcro’d animals, and which are sewn by Wong herself (proven by the sight of Wong assiduously sitting at a sewing machine fabricating fake dollar bills before the start of the show). There are also a few well-placed bits of video and audio supplementing the story but for the most part it’s all Wong all the time as she fills the stage with her kinetic and engaging, high energy performance.

As Wong notes, the show is all about delving deeper into a subject than a cursory facebook thread can do, proving the value in taking action in real life instead of being glued to the screen night and day. As someone whose primary visual aesthetic experiences are mediated (that is, I watch a lot of movies) it’s always fun for me to see live theater and Wong’s show is one of the most original that I’ve witnessed in a while. I’m looking forward to the next chapter in her ongoing performative observations.

The Glamorous Life: Human Capital film review

So there was a brief frisson of recognition amongst my film and art pals this morning to the video of Swedish director Ruben Östlund reacting to the news that his film Force Majeure hadn’t been nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Though it was pretty cheeky of Östlund to assume his film was a shoo-in, a lot of us artist types could totally relate to his mild freakout in a New York City hotel room (“Don’t undress!” pleaded his companion) as he faced this unexpected diss. Since constant rejections are part of the film/art world game, I definitely had a sympathy flinch or two when I watched the clip on my newsfeed. Östlund has since said that his reaction was sincere, (though some observers think he was pranking, especially since the video showed up on his production company’s youtube channel), but whether or not his mancrying was staged or spontaneous, it wasn’t too far from how I’ve felt many a time in the past. Of course, only five films from around the world get nominated and most do not, so Östlund is in plenty good company.

Another great movie that didn’t get nominated for the Oscar is Human Capital, Italy’s entry into the foreign-language sweepstakes. Opening this weekend, the movie is a cleverly structured look at class, privilege, greed, and desire in contemporary Italian society. The film opens with a quick sequence of events in which a bicyclist is hit by a car on a lonely country road, with the car’s driver continuing on without stopping. The movie then flashes back six months to deconstruct the events leading up to the hit-and-run from the various points of view of several key players including Dino, a scruffy social climber who mortgages his house to buy into a shady hedge fund, Carla, the anxious wife of said hedge fund’s unctuous manager Giovanni, and Serena, Dino’s teenage daughter who is involved with Carla and Giovanni’s spoiled son Massimiliano. Along the way the film touches on the social and economic divides within Italian society and the price that some people are willing to pay in order to advance themselves.

The film is sleek and fast-moving, efficiently weaving together the disparate versions of the story into a satisfying whole. Director Paolo Virzi has a sharp eye for social foibles and finds a lot of bone-dry humor in the characters’ dire situation. One amusing scene in which a group of catty drama aficionados critique the state of contemporary theater arts demonstrates Virzi’s knack for quickly and clearly delineating character traits and interpersonal tensions. He also elicits uniformly solid performances from his cast, lead by newcomer Matilde Gioli’s levelheaded turn as Serena—also good are veteran actors Fabrizio Bentivoglio as the cluelessly ambitious Dino and Valeria Bruni Tedeschi as the mournful, jittery Carla. Though based on a novel originally set in Connecticut, the story makes an effective transition to the suburbs of Milan, with Giovanni’s luxe marble villa, complete with indoor swimming pool and private tennis courts, contrasting with the Dino’s messy middle-class abode.

Director Virzi uses the multiple-point-of-view narrative technique, popularized in Kurosawa’s Rashoman back in the 1950s, to underscore the vast chasm between the stratified social classes in contemporary Italy. All of the characters believe in the veracity and reliability of their perspectives and for the most part can’t see beyond their own noses, suggesting a lack of empathy that contributes to social anomie. The exception to this is Serena, whose great sympathy for the plight of others makes her the moral center of the film. Virzi privileges her perspective by concluding the film’s fractured narrative structure with Serena’s point of view, which adds a small spark of hope that humanity might still rise up from the depravity, greed, and selfishness embodied by the other characters in the film.

A quick tip: this week is the start of the 13th Noir City Film Festival at the glorious Castro Theater in San Francisco. The ten-day festival is chock full of treats, many projected from 35mm prints. Favorite noir actors including Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Ryan, and directors Fritz Lang, Douglas Sirk, and Robert Siodmak, among many others, have films in the program, which is always a great time. Don’t miss it—I certainly won’t.

Human Capital

Opens January 14,

Landmark Opera Plaza, San Francisco

California Film Institute, San Rafael

January 14-24, 2015

Castro Theater

San Francisco

The Ferguson Masterpost: How To Argue Eloquently & Back Yourself Up With Facts

I’m in Asia right now so I’m viewing the Ferguson grand jury verdict aftermath from afar, but this article is an outstanding resource for talking about all the issues around it. I can’t add too much more to it since it’s thorough and comprehensive.

In The Still of the Night: Hong Kong Cinema film series

2014 was a pretty good year for Hong Kong movies and this year’s Hong Kong Cinema, the San Francisco Film Society’s annual film series from the former crown colony, reflects this uptick in cinematic quality. Recent output from brilliant directors Ann Hui, Pang Ho-Cheung and Fruit Chan are part of the mix, superstars Chow Yun-Fat, Tang Wei, Nicholas Tse, and Louis Koo (twice) are featured players, and the films run the gamut from crime thriller (Overheard 3) to youth romance (Uncertain Relationships Society) to wuxia pian (The White Haired Witch of Lunar Kingdom) and beyond. The series also includes a twentieth-anniversary screening of Wong Kar-Wai’s glorious slice of Hong Kong-meets-the-Nouvelle Vague, Chungking Express, which is definitely worth a watch on the big screen. A few other highlights follow.

From Vegas To Macau (dir. Wong Jing) is a cheesy quasi-sequel to Hong Kong’s many, many successful gambling comedy movies from the 1980s and 90s. Although luminaries including Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Andy Lau Tak-wah made their mark in gambling epics from that time, one of the pillars of the genre is God of Gamblers (1989), starring Chow Yun-Fat and directed by Wong Jing. In From Vegas To Macau Chow and Wong reunite in an attempt to resurrect their glory days, and by extension the glory days of Hong Kong movies, and the current film is a reminder of the best and worst of those times. In the plus column is Chow cutting loose in a wacky Hong Kong comedy, which helps to counter his mostly disappointing 10-plus years sojourn to Hollywood and which enables him to regain his crown as the Chinese god of actors. Appearing in the sidekick role, Nicholas Tse is an earnest straight man, and Chapman To overacts mightily to insure that Cantonese-language cinema’s laff-riot slapstick tradition continues.

For anyone who’s only familiar with Chow Yun-Fat’s iconic work as a soulful gangster in John Woo movies (and who haven’t seen him as a childlike amnesiac in the original God of Gamblers), this zany farce should be an eye-opener, as Chow turns on the high-pitched giggle and the crazy dance moves as a Ken, the godly gambler/con man at the center of the film. Watching a Wong Jing movie is kind of like blindly sticking your hand into a big mysterious barrel—you never know what random trash you’re going to pull out, and From Vegas To Macau is no exception. Wong strings together a series of vignettes and set pieces without regard to narrative logic, each scene clashing violently with the the others, and the tone of the film swings from action to slapstick to farce, with kung fu, booby-traps, CGI-enhanced card-shuffling, and fat-chick jokes all a part of the overstuffed mix. While it’s not a good movie in any sense of the word, its manic energy and illogical construction combined with the spectacle of Chow Yun-Fat goofing his way through a typical Hong Kong comedy makes it a decent timepass.

At the other end of the cinematic spectrum is Ann Hui’s The Golden Era, starring Tang Wei (Lust, Caution) as iconographic Chinese author Xiao Hong, who worked during the Republican era in China (she was born in 1911 and died in 1942) and who was one of the first modern-day female writers in the country to gain recognition. The film is beautifully made, with a lot of money evident in the stunning cinematography, costumes, and art direction, and boasts an excellent cast, but at three hours it’s overly long and at times glacially paced. The film makes liberal use of direct address, including an opening speech by Xiao Hong herself as she announces her birth and death dates, adding a self-reflexive layer to the narrative structure. Tang Wei is thoughtful and arresting as Xiao Hong, who was born into a patrician Chinese family but subsequently lived in poverty and uncertainty for much of her short life. However, her performance lacks a sense of agency and ferocity that a more intense actor might have brought to the role. In addition, those viewers unfamiliar with Xiao Hong’s body of work might be at a loss as to her significance, although many of the supporting characters repeatedly attest to her importance in China’s literary canon. Still, it’s interesting to see what director Hui has done with a generously budgeted film set in historical mainland China, since much of her oeuvre have been in the vein of A Simple Life or The Way We Are, which are much more quickly sketched stories deeply rooted in contemporary Hong Kong. Although there are stylistic differences between those movies and this one, Hui’s filmic intelligence shines through, as she’s made a smart and intriguing picture about the intersections of history, art, politics, and creativity.

Splitting the difference between Wong Jing and Ann Hui is Pang Ho-Cheung’s Aberdeen, which is an engaging look at contemporary Hong Kong through the lens of several intertwined relationships. The film follows the lives of the members of two related families, including a thirty-something actress/model (Gigi Leung) who is transitioning from her ingénue stage to something less well-received; her husband (Louis Koo), who is concerned that their daughter isn’t as pretty as he thinks she should be; his sister (Miriam Yeung), who’s obsessed with her fraught relationship with her late mother; and her husband (Eric Tsang), a doctor who’s making time with his receptionist. Intercut with these various subplots are a beached whale, unexploded WWII ordnance in the heart of Hong Kong, fantasy sequences with larger-than-life lizards, and Taoist funeral rituals. By interweaving these disparate elements director Cheung examines notions of beauty, fame, family, and loyalty amidst the backdrop of modern-day Hong Kong. The film continues in the vein of much of Cheung’s past work exploring Hong Kong life and relationships, which range from the brilliantly satirical Vulgaria to the rom-com Love In A Puff to the dark and disturbing Isabella.

In some ways Aberdeen recalls the glory days of UFO, the United Filmmkaers Organization production house that back in the 1990s was responsible for a slew of dramedies including Dr. Mack; Heaven Can’t Wait; Tom, Dick, and Hairy; and Twenty Something. UFO movies were smarter and less formulaic than the typical commercial Hong Kong output of the time and starred early 1990s superstars like Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Tony Leung Ka-Fei, Karen Mok, Jordan Chan, and Anita Yuen, all of whom were looking for prestige projects that were a break from Kong Kong’s usual kung-fu historicals or generic crime movies. Aberdeen carries on in this tradition, which stars current A-listers Louis Koo, Miriam Yeung, Eric Tsang, and Gigi Leung, as well as appearances from Hong Kong movie vets Ng Man-tat and Carrie Ng, in a quality production by a name-brand director. For the most part, although flawed, Aberdeen is infinitely more intelligent and watchable than much recent commercial Hong Kong cinema and gives its cast members a good opportunity to stretch out and to exercise their acting chops.

Hong Kong Cinema runs from Nov. 14-17, 2014 at the Vogue Theater in San Francisco. Go here for ticketing and full schedule.

Cool Like That: Who We Be book review

Jeff Chang’s latest book, Who We Be: The Colorization of America (St. Martin’s Press), dropped last week and it arrives as the United States is in the midst of another particularly fraught period of racial politics. As recent events in Ferguson, MO have indicated, Chang’s book argues that we as a country and a culture are a long way from becoming the post-racial society supposedly heralded by the election of Barack Obama, yet despite the seemingly dire straits that we’re in, all is not hopeless. In WWB Chang recounts the effects of the changing demographics in the U.S. since the mid-twentieth century, from desegregation through multiculturalism to the shooting of Trayvon Martin and beyond, investigating the ways in which visual culture intersects with current and historical events.

WWB is an amazing tome, encompassing topics as broad as the civil rights movement and as focused as Budweiser’s “Wassup” ad campaign. The book is an outstanding look at the ways in which we as a people in the United States since the mid-twentieth century have moved through a sea change of perceptions, representations, and reflections of racial relations.

Beginning in the 1960s, Chang’s book interweaves topics as diverse as the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy,” the 2001 World Trade Center attacks, the subprime mortgage scandal, Occupy Wall Street, and the psychology of advertising. Chang focuses on a range of culture creators including cartoonist Morrie Turner, whose comic strip Wee Pals featured a multiracial cast of kids, Faith Ringgold, an early advocate for the Black Arts Movement, Daniel Martinez, known for his performance art/museum tag/culture bomb from the 1993 Whitney Bienniel, and Shepard Fairey, designer of both the Andre The Giant “Obey” street art campaign and the 2008 Obama “Hope” image.

Chang does a great job exploring the ways in which real life, visual art, and commerce interact and influence each other. For instance, Chang explores a proto-multiculti Coke ad campaign from the early 70s that tried to latch onto the youth culture and nascent ethnic studies movement of the time but that didn’t mention any of the harsher realities of, say, the Watts riots. Another section of the book drills down into the racism and elitism of the 1980s and 90s New York visual arts scene, including a particularly culturally tone-deaf incident surrounding the white artist responsible for “The Nigger Drawings.” Chang closely examines this volatile period during which contemporary arts gatekeepers like the New York Times, gallery directors, and curators were forced to confront their biases against creative work by artists of color and queer artists, which reached a crescendo during the controversial 1993 Whitney Bienniel, which was vilified by the art establishment as “a theme park of the oppressed.” Chang then discusses the ways in which these so-called culture wars in turn lead to the commercialized multiracialism of the United Colors of Benetton “Colors” magazine and ad campaign.

Chang also astutely looks at what he calls “the paradox of the post-racial moment,” wherein the U.S can elect Barack Obama president, yet still has trouble reconciling Obama’s biracial identity. Chang’s analysis is particularly keen when exploring the current confused state of race relations in the U.S., describing what he calls the tendency for many people to be “colormute,” that is, to avoid talking about race for fear of being accused of racism. He ironically notes the convoluted logic behind those who frown on discussing race in any way, stating, “If bad people had used race to divide and debase . . . then good people would be polite to never acknowledge race at all. It was better not to say anything than to risk being seen as a racist.”

Chang concludes his book with two contrasting case studies–a detailed look at George Zimmerman’s murder of Trayvon Martin and the rise of the DREAM Act, the proposed federal legislation that addresses the citizenship status of undocumented young people brought to the U.S. while children. By juxtaposing these two cases Chang emphasizes the fact that, while the Martin killing demonstrates that the U.S. remains far from being a post-racial society, there is still reason for hope, as seen in the increased activism by immigrant youth of color under the DREAM Act.

Chang’s writing is clear and accessible, and his analysis is thoughtful, concise, and innovative. Though by no means a dis on the theory queens among us (and you know who you are), after recently wading through a few visual culture publications, it’s a pleasure and a relief to read an author who writes with clarity without sacrificing intelligent intellectual commentary. Who We Be is a significant and essential addition to the study of contemporary U.S. art, culture, and politics.

Jeff Chang is on a book tour to promote WWB! Find out more here.

Que Caramba Es La Vida: Mill Valley Film Festival 2014

The Mill Valley Film Festival’s 2014 edition starts this weekend and as per usual it’s a star-studded affair, with guest appearances by the likes of Hilary Swank, Jason Reitman, Billy Joe Armstrong, Ellie Fanning, Laura Dern, Metallica, and many more Hollywood glitterati. The program also boasts an outstanding lineup of documentaries, including several by local filmmakers, so the reasons for driving across the Golden Gate Bridge (or the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge, depending on your homebase) are manifold.

This year the festival is spotlighting Spanish-language cinema from around the world, including the excellent documentary Que Caramba Es La Vida, an intriguing portrait of the fierce and talented women mariachis of Mexico City. Directed by veteran German filmmaker Doris Dörrie, the movie documents the experiences of several female performers working to make a mark in a field dominated by men. The film is shot mostly verite-style with no narration, as each of the women describes how she came to be a mariachi and why she continues in the business. Some come from mariachi families, with parents or grandparents who performed before them, while others are the first in their families to perform. A particularly compelling story is that of Maria del Carmen, a mariachi singer who lives with her single mom and young daughter in a small apartment in Mexico City. Del Carmen’s mother recalls that even as a girl, her daughter Maria had a voice “that went right through you,” and this is pretty apparent after hearing del Carmen soulfully belt out a couple songs in the Plaza Garabaldi, which is home to scores of mariachi bands plying their trade every night. The film depicts del Carmen’s everyday performance prep routine, as her mom and daughter help her with her makeup and hair, as well as revealing her concerns for her daughter’s future as a female growing up working-class in Mexico. The movie also follows Las Pioneras, a group of older female mariachi groups whose members who are now in their sixties and seventies and who started out as mariachis in the 1950s as teenagers and young women. The last quarter of the movie follows the Dia de los Muertes celebrations in Mexico City, neatly contextualizing the mariachi tradition. Que Caramba Es La Vida effectively looks at some of the social and cultural milieu surrounded the women, including the effects of drug dealers, misogyny, poverty, and crime on their ability to keep performing.

Mexican music of a different sort is profiled in For Those About To Rock: The Story of Rodrigo y Gabriela. Rock journalist and first-time director Alejandro Franco narrates his very accessible portrait of the popular Mexico City guitar duo, from their roots in the capital listening to thrash and heavy metal like Megadeth, Metallica, and Slayer as teenagers. Both subjects are fluent in English and were raised in middle-class Mexican families, so their stories for the most part are very different from their mariachi counterparts in Dörrie’s film. The film is a standard biopic of a successful musical outfit so, unless you’re a big Rodrigo y Gabriela fan, the movie is less compelling than Dorrie’s movie. The film starts out strong, quickly and succinctly contextualizing the Mexico rock music scene, but bogs down in the middle as it becomes a fairly linear recounting of R&G’s career.Although the film is about musicians, one of its shortcoming is that there isn’t actually enough of R&G’s music in the earlier part of film, so if you’re unfamiliar with the duo you might not know what the fuss is all about. The film makes the mistake of telling and not showing, which weakens its impact—there are a lot of talking heads explaining things and not enough things happening instead. Whereas Que Caramba takes place on the streets and in the plazas of Mexico City, For Those About To Rock happens mostly in recording studios, backstage, and at clubs, and concerts, and is more of a fannish tribute about legend-building than an incisive look at the duo. There is also not much dramatic tension—the director refers to the story as a “fairy tale’ and it’s presented as such, with R&G destined to achieve their rock star ambitions. The viewer learns very little about either musician’s personal life or any deep, compelling reasons for why they make music other than “it’s fun”, and the film lacks a strong sense of a cultural context for who they are and where they came from. The film ends with about ten minutes of live concert footage that only underscores the relative paucity of music in the rest of the film, which may be enough of a reason for admirers of Rodrigo y Gabriela to watch the film.

The Mill Valley Film Festival eleven days beginning on Oct. 2 in various theaters in and around Mill Valley. Go here for complete schedule and ticket information.

Ruffneck: Keaton, Laurel, and Hardy at the SF Silent Film Festival

Buster Keaton’s The General is one of those movies that are on every cinephile’s best-of list, and with good reason. Elegantly structured, coolly executed, and funny as hell, the film was Keaton’s own favorite, although it was the movie that almost ruined his reputation when it first came out. It took a long time to shoot, was prohibitively expensive, and absolutely did not make bank when it was released—Keaton’s rep as a comedic star took a big hit and his studio reined him in after The General‘s box office failure. The movie was anything but well-received when it was released in 1926, although it’s now considered a classic.

The storyline follows a railroad engineer and wannabe Confederate soldier during the Civil War (nimbly played by the diminutive Keaton) who traces the theft of his beloved railroad engine, named The General, behind Union lines. The movie features some of the most beautifully choreographed stunts of the silent era, involving huge piles of rolling logs, steam engines on collision course, and the spectacular demise of a full-size locomotive. The sight of an actual train engine falling many dozens of feet from a bridge to a riverbed is still amazingly impressive, even in this age of CGI and digitally created special effects. The film is Keaton at his best, with its stripped down, symmetrically structured narrative, its large-scale, dangerous, and perfectly executed stunts, and its underdog hero struggling within a vastly unsympathetic world.

Silent film comedy of an entirely different sort are the Laurel and Hardy two-reeler short films, Two Tars (1928) and Big Business (1929). Two Tars follows a day in the life of a couple of sailors on leave in Los Angeles as they go joy-riding among the California chaparral with a couple of dames. Although Stan and Ollie play sailors, all of the action in the twenty-minute movie takes place on a pair of landlocked Southern California roadways. Featuring Laurel and Hardy’s signature physicality and escalation of destruction, the short also includes some very suggestive digital manipulation of a gumball machine as well as several excellent Stan Laurel pratfalls. The short concludes with an epic traffic jam that would make Godard proud that illustrates the primal allure of large-vehicle destruction, the weaponization of cow pies and rotten tomatoes, and a gal getting a faceful of black ink.

Big Business is even more of a felon’s wet dream, as a small misunderstanding rapidly escalates into complete mayhem, resulting in an entire house vandalized down to its spinet piano and brick chimney. L&H play door-to-door Christmas tree salesmen plying their wares in the sunny, overexposed 1920s Southern California suburbs, which were about as sparsely populated as the high desert at the time. The two get into a scrap with a feisty homeowner and soon the axes are out and windows, doors, and a Model T fall victim to the OTT belligerence of the battling adversaries. The humor derives from the extreme reactions of both Stan and Ollie as well as their antagonist, played with righteous fury by L&H regular James Finlayson.

All three of these comedy classics are screening as part of Silent Autumn, the San Francisco Silent Film Festival’s one-day event on Sept. 20 at the glorious Castro Theater. Also notable are screenings of new restorations of The Son of the Sheik, starring the beautiful Rudolph Valentino, and the German expressionist classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. As per usual with all SFSFF events, each program includes live accompaniment, by silent film score maestro Donald Sosin as well as the always innovative Alloy Orchestra. Go here for complete schedule and ticket info.

Typical Girls: Kenji Mizoguchi film series at the Pacific Film Archive

The Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley comes through once again with another outstanding series, this time focusing on legendary Japanese filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi. Running through the end of August, this set gives you the chance to see much of Mizoguchi’s amazing oeuvre on the big screen and in glorious 35mm.

Along with Akira Kurosawa and Yasajiro Ozu, film historians consider Mizoguchi one of the Holy Trinity of golden-age Japanese filmmakers—the work of these seminal directors spanned much of the early and mid-twentieth century and has received massive critical attention. Among those three, however, Mizoguchi’s star has dimmed a bit, due in part to the somewhat unrelenting bleakness of his films. But his portrayals of the plight of women in a patriarchal society are pretty key, and his intricate camerawork and direction are still fresh and revelatory. The PFA series is a great chance to witness Mizoguchi’s masterful use of the filmic medium to examine the effects of a brutal and uncaring society on individuals caught in its strictures.

Mizoguchi’s brilliant use of the camera is in full effect throughout the series. Famous for including a minimum of close-ups and often shooting his scenes in extended master shots (a style dubbed “one scene, one cut”), he performs a kind of cinematographic butoh, with ultra-slow, beautifully choreographed push-ins, pans, and dollies that mesh with the characters’ actions and dialog in an intricate, intertwined choreography.

The PFA series include most of Mizoguchi’s well-known jidai-geki (historical dramas) like the popular ghost story Ugetsu, winner of the Silver Lion Award for Best Direction at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, and The Life of Oharu, a masterpiece that’s a sad tale of a woman’s oppression, told with clockwork precision and driven by a bravura performance by Kinuyo Tanaka. In addition to his more famous historicals, the PFA is also screening several of Mizoguchi’s modern-day films. Mizoguchi is recognized for his period pieces, yet like his compatriot Akira Kurosawa he also directed several films that scathingly examine issues and problems of 20th-century Japan. As with his period films, these modern-day movies often center on the plight of women in a straight-laced society. Osaka Elegy (1936) is a bleak, brilliant, and economical portrayal of the social strictures that constrained women in a pre-feminist age. Elegy is buoyed by Mizoguchi’s sympathetic portrayal of the female protagonist, surrounded by exploitative, weak, or cowardly male figures who lend little support when the heroine falls on hard times. A proto-noir filled with deep shadows and geometric compositions, the film displays Mizoguchi’s mastery of the medium even in the 1930s.

Also from 1936, Sisters of the Gion is a surprisingly modern and unsympathetic take on the hard-knock geisha life, full of Mizoguchi’s gliding camerawork and one-take marvels. Hard-as-nails Omacha and her more sensitive sibling Umekichi are two low-end geisha in the Gion, Kyoto’s licensed pleasure district, who are struggling to make ends meet by landing “patrons,” customers who are mostly old wizened married guys. The film is a cutting indictment of the capitalist system that’s all about the money and is a good example of a Mizoguchi keikō-eiga (tendency film), which literally displays his socialist tendencies. Omacha is the deal-maker, trying to manipulate the system to escape the oppression of poverty, sexism, and misogyny, while Umekichi desperately believes that the system will work in her favor. The PFA series screens Mizoguchi’s remake of Sisters of the Gion, A Geisha (1953), which updates the story to postwar occupied Japan and which stars the famed Ayako Wakao in one of her first film roles.

The PFA series concludes with Mizoguchi’s last movie, Street of Shame (1956), which is an excellent example of Mizoguchi’s use of film to examine social problems. The story concerns a group of prostitutes in postwar Tokyo who struggle to overcome an andocentric culture insensitive to the needs of women. In a role that’s a departure from her parts in the period films Rashomon and Ugetsu, Machiko Kyo plays Mickey, a material girl who’s not above stealing her co-workers’ customers or blithely overextending her credit at local shops. Ayako Wakao as Yasumi is a no-nonsense working girl who plans to escape the brothel by becoming a moneylender and shopkeeper. The men in the film are for the most part weak, craven, or venal, preying on the female protagonists and only valuing them for their bodies or their beauty, or despising them for their vocation. Yet Mizoguchi makes it clear that the women are prostitutes only because they are given little other choice in society. In one amusing scene one of the women who’s left the profession to marry a small-town cobbler returns to the brothel. She laments that marriage is worse than selling her body to strangers as her husband forces her to work in the shop from morning to night, then expects dinner and sex at the end of the day. Mizoguchi’s narrative uses the women’s plights as a critique of capitalism, an exploration of the uncertainty and despair of post-war Japan, and an indictment of the constraints of a patriarchal society.

While many of Mizoguchi’s films are available on DVD, Mizoguchi is absolutely a big-screen director. His subtle use of the camera and his epic portrayals of women and men struggling to overcome their fate deserve to be appreciated in a movie theater and, as usual for this excellent venue, the PFA serves up his films as they were meant to be seen.

Kenji Mizoguchi: A Cinema of Totality

June 19, 2014 – August 29, 2014

Pacific Film Archive

2575 Bancroft Way

Berkeley CA 94720

Recent Comments