Posts tagged ‘film’

Love Buzz: 2025 Mill Valley Film Festival

The 2025 Mill Valley Film Festival is upcoming this weekend and there is a treasure trove of Asian and Asian American films on the docket. Among these are some of the buzziest films from the current film festival season.

The festival’s opening night film is Hamnet, Chloe Zhao’s interpretation of the backstory of the creation of Hamlet. Zhao has a decidedly singular vision and the film promises to be an eye-opening and unexpected journey. Hamnet premiered at the Telluride Film Festival a few weeks ago and as with all of Zhao’s films it garnered a lot of attention for its unconventional vision and storytelling.

Probably one of the most talked-about films at the recent Venice Film Festival, Park Chan-Wook’s newest joint No Other Choice has its Bay Area premiere at MVFF ahead of its theatrical release later this year. With an A-list cast toplined by Lee Byung-Hun (Squid Game; Mr. Sunshine; A Bittersweet Life) and Son Ye-Jin (Crash Landing On You: The Pirates), the film is a black comedy about a white-collar worker (Lee) whose world is turned upside down when he suddenly loses his cushy corporate job. As expected in a Park film, things go sideways quickly. No Other Choice garnered a long standing ovation (reported as anywhere from six to nine minutes) at Venice and has presold to 200 countries.

Taiwan represents at MVFF with Left-Handed Girl (dir. Shih-Ching Tsou), another festival favorite that premiered at Cannes. Set in the night markets of Taipei, the film follows a single mother and her two daughters as they navigate life in the big city. The film is Taiwan’s nominee at the Academy Awards for Best International Feature.

Diamond Diplomacy (dir. Yuriko Gamo Romer) looks at the popularity of baseball in Japan as well as among the Japanese American community, exploring the ways that the game reflected and facilitated US-Japan relations both on and off the field. An encyclopedic look at its topic, the film spans more than 150 years from just after the Civil War to the present day, with appearances by Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Ichiro Suzuki, Masanori Murakami, and many more. The film is an intriguing examination of how sports, politics, celebrity, and soft power intertwine.

Chang Chen (A Brighter Summer Day; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; The Soul) stars in Lloyd Lee Choi’s directorial debut, Lucky Lu, which also premiered at Cannes. The film follows a New York City delivery driver, played by Chang, through a harrowing series of events as he roams the city in search of an acquaintance who’s run off with a large sum of his money.

Living The Land premiered at the Berlinale last February where director Huo Meng won the Silver Bear for best directing. The film is set in 1991 and looks at life in a small village in China as its inhabitants live through the vast changes in the country at the time.

Along with these feature films there are a plethora of shorts by Asian and Asian American directors among the festival’s several shorts programs. It’s a great chance to see these films in the friendly confines of MVFF, since unlike the feature films many of them might not get widespread distribution.

All in all, this year’s MVFF is an excellent opportunity to catch the newest and hottest Asian/American movies.

Rise Up: Frameline San Francisco International LGBTQ+ Film Festival review

Because shit is so chaotic in the US right now I almost forgot about the Frameline LGBTQ+ film festival this year, but fortunately a friend reminded me that it was happening. I was lucky enough to do a quick pivot and catch a few select films at the festival.

The Hong Kong indie film Queerpanorama, directed by Jun Li, was definitely the edgeist of the films I saw. I’ve seen two of Jun Li’s previous films, Tracey (2021) and Drifting (2021), both of which focus on people on the margins of society in Hong Kong, and Queerpanorama follows in the same vein.

The premise is simple: A young guy in Hong Kong has a series of one-nighters with a variety of men. He asks them a bit about their life story before sex, then assumes their identities with the next hookup. It’s actually more benign than it sounds, without being overly dramatic or sensationalistic and in some ways it shows how we take on parts of everyone we encounter. It’s also about finding connections in a busy, anonymous city. The film captures the loneliness of modern life, as embodied by the fragility and strength of lead actor Jayden Cheung’s delicate physicality.

The conversations in the film are quite tender, often contrasting with the vigorous sex scenes that follow them, and the film emphasizes that the talking and the fucking are just two different ways of trying to connect. At the same time, the main character always keeps his distance, pointedly mentioning his boyfriend as well as specifying that each encounter is a one-off. The character endlessly circles, never fully engaging despite the physical intimacy, underscoring the difficulty of truly engaging in these times.

Taiwan’s Silent Sparks (dir. Ping Chu) is much more conventionally styled, a moody and brooding film that recalls classic film noir, but queer. An ex-con gets out of prison and tries to adjust to life on the outside but the world of crime keeps calling to him. The twist here is that the film explores the homosociality of prison and gangster films and reveals the unspoken homoeroticism in many of them. It’s a classic crime film setup but it says the quiet part out loud.

The South Korean narrative Lucky, Apartment (dir. Kangyu Garam) follows a lesbian couple in Seoul dealing with societal expectations, metaphorically represented by a very stinky apartment just below theirs. The film cleverly connects past and present and ultimately demonstrates the significance of chosen family and creating community across generations. Director Kangyu Garam uses a light touch in her critique of homophobia, societal pressures to marry, gender roles, and other issues facing queer women in Korea.

Jota Mun’s documentary Between Goodbyes follows Mieke, a queer South Korean adoptee as she navigates between her Korean family and her life in the Netherlands, where she was raised by a deeply religious single mother. A much harsher critique of the capitalist system that promoted Korean adoptions than Deann Borshay Liem’s groundbreaking Korean adoptee film First Person Plural (2000), the film is an intersectional look at the ongoing impact of international adoption.

I also caught the shorts program It’s a Family Affair, which included a handful of Asian films.

Tara (dir. Ashutosh S. Shankar) follows the story of a transfemme in India who starts dating a hunky new man, but the kicker is that his family isn’t opposed to her based on her trans identity but on the fact that she’s dalit and he’s brahmin. The film is a sensitive look at caste-based prejudice in India.

Correct Me If I’m Wrong (dir. Hao Zhou) is a quirky little look at the lengths a Chinese family will go to in order to straighten up the girly boy scion of the family, including various traditional remedies that attempt to cure what ails him. The results, however, are dubious.

Grandma Nai Who Played Favorites (dir. Chheangkea) is a droll and entertaining tale of the foibles of the ghost of a Cambodian grandma who reappears to comment on her queer grandson’s impending nuptials to a woman.

The highlight of the festival for me was Rashaad Newsome and Johnny Symons documentary Assembly, which follows the creation of Newsome’s multi-layered Afrofuturist performance piece of the same name. Although Newsome and Symons are very different types of filmmakers their collaboration on Assembly somehow managed to effectively mesh their very disparate aesthetics. During these grim times in the US and beyond it was a tonic to see a piece of art that addressed difficult questions with joy, hope and beauty. I entered the film in a very dark state of mind and left afterwards uplifted and inspired.

During his introduction to Queerpanorarma, director Jun Li spoke about the optimism and happiness he witnessed visiting Frameline in 2015 when the community was celebrating the legalization of gay marriage, as compared to now, when things both in Hong Kong and the US are much more dire. We are definitely in some rough waters right now but events such as Frameline offer hope that creativity, joy, and passion will somehow see us through.

Winter Again: Harbin film review

The South Korean historical action thriller Harbin opened recently in the US and as expected it’s a gorgeously appointed piece of commercial cinema. Based loosely on the true story of Korean independence fighter Ahn Jung-Geun, the movie is set in 1909 at the very start of Japan’s occupation of Korea. The film is full of A-list stars, beginning with Hyun Bin (Crash Landing On You) as Anh, as well as Park Jeong-Min (Reply 1988; Hellbound), Jo Woo-Jin (Hard Hit; Mr. Sunshine, The Drug King) and Lee Dong-Wook (Goblin: The Lonely and Great God), among several others. (I believe that Woo Jung-Sung also makes a cameo as a drunken arms-dealing hermit but he’s so covered with matted hair that I wasn’t quite sure.)

Beautifully shot by Hong Kyung-pyo (Parasite; Broker; Burning), the movie opens with a striking overhead long shot of Ahn wandering across a dark frozen lake that’s laced with white fissures. Set in the titular northern province of China, Hong also takes advantage of Harbin’s icy wintertime, with shadowy leafless trees framed against gray skies and snowy cityscapes creating a bleak, moody atmosphere.

Woo Min-Ho has directed two outstanding films starring Lee Byung-Hun, the corporate crime film Inside Men and the political thriller The Man Standing Next, as well as the Song Kang-Ho vehicle The Drug King, which has a retro Tarantino vibe, and in those films as well as in Harbin he evokes a strong sense of place and history. In Harbin, Woo stages several tense scenes in swaying train cars, their constrained spaces contributing to the tension of the action, while other scenes utilize a chiaroscuro lighting scheme, with characters’ faces in deep shadow or obscured by hats, which echoes their moral and ethical ambiguity. Woo also effectively uses wide shots and long takes, as when he frames Ahn in a wide shot as he stumbles through the wreckage of a bombed-out building, his lone figure dwarfed and surrounded by the numbers of dead bodies he finds. The framing magnifies his anguish and contributes to his sense of overwhelming grief and guilt.

Hyun Bin as Ahn is Hyun Bin, meaning he is broodingly handsome even with long unkempt hair and dirt on his face. He effectively conveys Ahn’s single-minded han, but I couldn’t help but wonder what Lee Byung-Hun or Hwang Jung-Min or Ha Jung-Woo, all of whom possess mad acting skilz, would’ve brought to the role.

The movie has been at the top of the box office in South Korea in the three weeks since its release and it has a particular resonance at this moment in time. A Japanese official in the film observes, “Korea’s common people are the most troublesome. Their nation gives them nothing, but in times of national crisis they wield a strange power,” and this sentiment applies directly to current events in South Korea. President Yoon Suk Yeol has just been arrested for illegally declaring martial law at the start of December, as well as having been impeached, in large part due to citizens protesting in the streets every day for the past six weeks despite the freezing cold winter weather in Seoul. After the events depicted in Harbin, Japan occupied Korea for 35 more years, but after much armed resistance and much blood spilled by independence fighters, Korea eventually regained its sovereignty. Harbin is a reminder to those currently demonstrating in Seoul that the road to freedom may be long but ultimately justice can be served.

As someone facing the potential for an authoritarian regime here in the US, I also was uplifted by the film. Despite its typically dramatic flourishes, it’s still heartening to see a story where resistance matters and where evil forces can be vanquished. No matter how long it takes, the people of Korea didn’t give up and continue to not give up, which is a narrative that I need to see right now.

Experimental film in the time of coronavirus: CROSSROADS 2024 film festival recap

The Crossroads 2024 experimental film festival happened at Gray Area in San Francisco Aug. 30-Sept. 1, 2024, and it was excellent. I soaked up a lot of movies and saw a lot of friends so it was a very fine and enjoyable event. My very subjective diaristic experience below.

Day One

Got my new COVID vaccine on Friday afternoon so I was expecting a hangover sometime after that but by the time early evening had rolled around I was still feeling okay. So I headed over to Gray Area for the Opening Night screening, which was mobbed with experimental film stans. It was good to see such a big turnout for something that is relatively niche.

Program One included Simon Liu’s latest maximalist extravaganza, Single File (2023). Opening with an image of two people looking out the window at Hong Kong’s cityscape, the film is a frenetic, densely layered kaleidoscope overlaid with a percussive electronic soundtrack. The words Promise Rebuild flicker onscreen towards the start of the film and towards the end the film includes images of a large mass of people in the streets, which would now be illegal in Hong Kong. Created in the aftermath of the 2019 protests and the 2020 implementation of the repressive National Security Law in Hong Kong that criminalizes dissent, the film reflects this moment in the Special Administrative Region when oppositional voices have paused but not ceased and where they wait for a more opportune and less dangerous time to speak.

Day Two

Vaccine hangover kicked in and I felt mildly achy and feverish so I spent the day on the couch watching Korean dramas, which in some ways are stylistically the farthest I could get from experimental films. Hoped to feel better for Day Three on Sunday. However, although I couldn’t attend in person, I did manage to catch several of the films via the magic of online press screeners.

Among those I enjoyed Niyaz Saghari’s Ripple Effect (2024), an elegy to Iranian martyr Navid Afkari, who was executed by the Iranian government for participating in protests in 2018. The film opens with the brief quote, “The diver plunges into sea (death), but also into life (eternity), where he will discover the primordial waters of life” (Pierre Lévêque), and the film’s central imagery is a rephotographed clip of Afkari diving into a pool of water, suggesting that even in death Afkari remains a symbol of resistance.

I also liked Bisagras (2024), by Venezuelan filmmaker Luis Arnías, which was filmed in Senegal and Brazil and which utilizes contrasty black and white footage, with some negative imagery, to explore the linkages between slavery and colonialism in Africa and the Americas.The film’s ambient soundtrack is a nice change from a lot of the angsty noise-based soundtracks from a lot of the other films in the festival.

Day Three

COVID vaccine hangover completely gone as of Saturday night so I rallied to see three more shows on Crossroad’s final day at Gray Area. Consuming that much experimental content made it all a blur but I did enjoy new work by Deborah Stratman and TT Takemoto.

I appreciated the economical interweaving of images, text, and sound in Stratman’s Otherhood (2023). Rather than overexplaining, Stratman gives the viewer the benefit of the doubt, which creates a much more satisfying viewing experience.

TT Takemoto’s latest gem, For Jina (2024) is an ethereal blend of hand-manipulated film imagery combined with a dense, evocative soundtrack. The film is a tribute to Mahsa “Jina” Amini, an Iranian woman who died in police custody in 2018 after being arrested and beaten for wearing an “improper” hijab. Takemoto lifts the emulsion from photos and footage of Iranian women protesting after Amini’s death as part of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement as well as from the 1979 Women’s Day marches in Tehran, re-affixes it to clear leader, colorizes it with nail polish and then digitizes and slows down the footage to highlight the fleeting moments they’ve captured in the process. The film’s final image is of a woman defiantly shouting, suggesting that her voice will not be silenced. Though more fragmentary than some of their longer pieces, this short still demonstrates Takemoto’s sure hand with re-imaging found images and their continued interest in memorializing and elevating historical events that are threatened with erasure.

All in all, this year’s Crossroads was a great chance to see many experimental films as well as catch up with the many experimental filmmakers who were in attendance. As well as watching movies, these kinds of events are all about building community and I appreciated the chance to hang out, eat tortas, and shoot the breeze. It’s always a pleasure to get out and get away from my individual screens at home and to interact with real live people, along with watching movies on the big screen.

NOTE: Through Oct. 12 go here to watch Crossroads Online Echo, a streaming selection of Crossroads programming. Free!

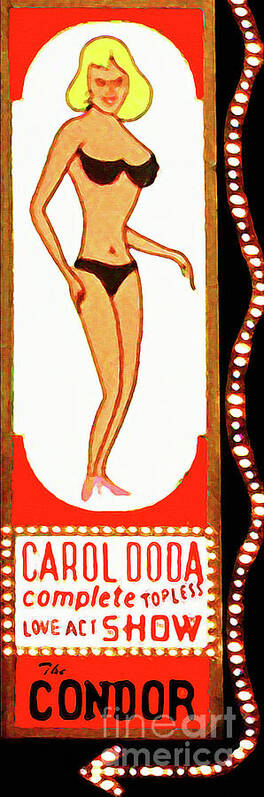

Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood: Carol Doda Topless At The Condor film review

San Francisco’s North Beach is right next to Chinatown, so growing up in the Bay Area I vividly remember seeing the giant neon sign at the Condor Club at Columbus and Broadway every time my family made the trek to the city for a wedding banquet or a red egg party. I always wondered who the woman in the billboard was and why she had bright red lightbulbs on her bra but of course it was not to be discussed with my parents or any other adults who happened to be driving the car. Once I got older I learned who Carol Doda was in a general sort of way but I didn’t know too many details about her life or how she came to have her likeness in lights at a club in North Beach, so I was happy to learn more via the new documentary, CAROL DODA TOPLESS AT THE CONDOR (dir. Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker), which takes its name from that very neon sign that mystified me as a kid. Doda started her career as a go-go dancer and cocktail waitress there back in the early 1960s and when she became the first performer to go topless in 1964 she became a sensation.

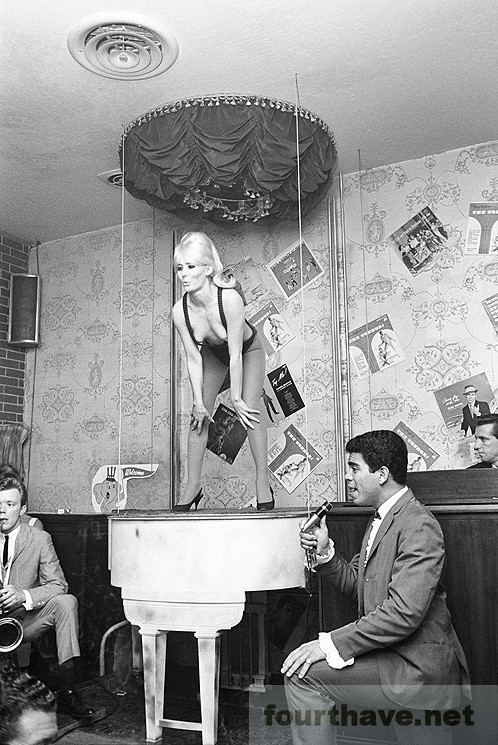

The film does a good job evoking the time and place when San Francisco was the hippest place around. In the early 60s the beatniks were fading away and the hippies had not yet taken over, but San Francisco was still the place to go for vacationing Midwesterners looking for edgy entertainment. Doda was at the center of the scene and people lined up around the block to see her dance and sing in her g-string. The film tells her story through interviews with Doda’s contemporaries as well as from archival interviews with Doda herself (she died in 2015) and features copious amounts of archival footage from back in the day.

For the most part, like most biographical documentaries the film emphasizes the positive. It hints at a bit of the darker side of Doda’s story including her unhappy marriage at a young age and her estrangement from her children from that marriage and there is one scary shot of the very large needle used for silicone breast enhancement (Doda went from a 34B cup to a 44DD using silicone). There’s also a harrowing tale of a fellow dancer who developed gangrene in her breasts because the silicone blocked her milk ducts when she tried to nurse her infant, but the film isn’t an expose of the wrongdoings of the boob job industry. Instead it focuses on the perspective of Doda and the other dancers interviewed who describe the financial and personal freedom that topless (and later bottomless/nude) dancing afforded them. The movie frames Doda as a proto-feminist who actively chose her profession and places her in the context of the sexual revolution, the Summer of Love, and the women’s liberation movement, arguing for the agency and self-determination of Doda and her fellow dancers.

The film also traces the rise and fall of North Beach, which by the 1980s had become a much seedier place, as illustrated by the questionable death of Jimmy “The Beard” Ferrozzo, one of the managers at the Condor. Ferrozzo had some unfortunate encounters with organized crime and in 1983 he was crushed to death after hours one night by the hydraulic piano that Doda danced on top of in her show. The film also points out that in the 60s, couples and businessmen made up a big part of the audience at Doda’s shows, but by the 80s it was primarily single dudes, probably in raincoats.

All in all the film is a fascinating, wide-ranging and entertaining look at the era, with Carol Doda literally emboding that era. It’s a fun watch and it satisfied my curiosity about that giant neon sign and the woman that it represented.

Recent Comments