Posts filed under ‘film festival’

Let It Shine: 2023 San Diego Asian Film Festival

Just got back from a quick and dirty one-day trip to San Diego to attend the San Diego Asian Film Festival (SDAFF). SDAFF is the biggest film fest in North America focusing on Asian/American films and artistic director Brian Hu and his team consistently program an outstanding blend of art house, genre, and indie films. Since I ride for Lee Byung-hun, I got the impetus for my trip when I found out that SDAFF was screening his latest film, CONCRETE UTOPIA (which is also South Korea’s entry in the upcoming Academy Awards). I had a bit of airline credit I had to use by the end of the year, plus a few points to spend on a rental car and a hotel so I made the decision to take a jaunt to sunny San Diego.

I arrived Sunday morning just in time to have some excellent chicken jook and to see a few friends at the filmmakers’ brunch. SDAFF is known for its great hospitality and this year was no exception. Then it was off to the movies, starting with the shorts program Astral Projections. MANY MOONS (dir. Chisato Hughes) was the standout film in this program, an essay film about the 1880s forced expulsion of almost the entire Chinese population of Humboldt county. Since I’d made THE CHINESE GARDENS about a similar occurrence up in Port Townsend Washington back in 2013 the topic was of particular interest to me. Hughes did a great job layering interviews, text. archival images, and other visual elements to question the facts and fictions around this notorious event.

After another pit stop at the reception area for a couple slices of pizza and some butter cookies I then saw the nouveau martial arts film 100 YARDS. Set in 19th century Tianjian, the film is co-directed by brothers Xu Junfeng and Xu Haofang, the latter of whom is known for writing Wong Kar-Wei’s THE GRANDMASTER, and this movie similarly attempts to re-imagine and revisit the martial arts genre, but with less success. Although the smoky greys and browns of the mis en scene create a striking visual tableau and the costumes, props and set design were all great, there were way too many fights and not enough character development to hold my interest. It was hard for me to care much about the main character’s daddy issues, although Jacky Heung and Andy On brought the skilz to their fight scenes.

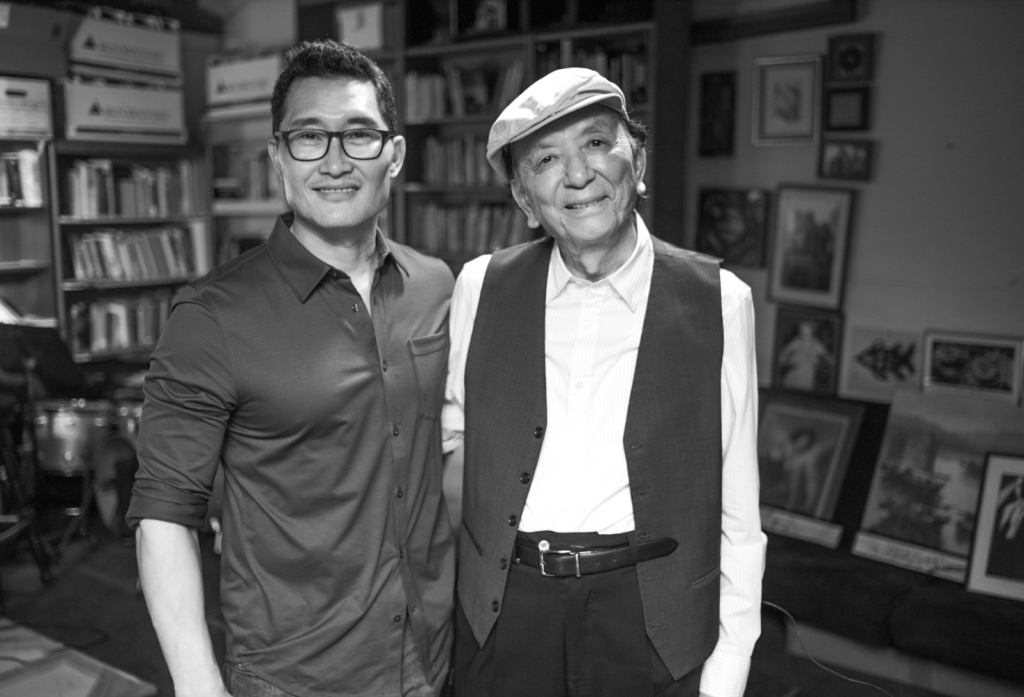

I then moved on to Yu Gu’s documentary, EAST WEST PLAYERS: A HOME ON STAGE. As Gu notes, she had less than an hour to cover nearly sixty years of the history of the legendary and influential Los Angeles-based Asian American theater company, but the film does an excellent job of doing just that. Gu pairs older and newer veterans of EWP such as George Takei, Daniel Dae Kim, James Hong, Tamlyn Tomita, and John Cho to discuss the significance of the troupe as a voice for Asian Americans in the theater. It was fun to see clips from the trove of archival footage of EWP as well.

By then I was contemplating how I would squeeze in time to grab a bite for dinner but decided to forgo eating to line up for the main event of my trip, CONCRETE UTOPIA. I first heard about this movie from my friend Anthony Yooshin Kim, who’d seen it at CGV in Los Angeles a few weeks prior. Unfortunately at that time there were no plans for a wider theatrical release in the US so when SDAFF announced it as part of its lineup I decided to catch it there, since I wanted to see it on the big screen. A dystopic story about the residents of the only apartment building left standing after a massive earthquake levels Seoul and starring A-listers including my man Lee Byung-hun, Park Bo-young, and Park Seo-jun (who makes his US debut in THE MARVELS this year), the movie did not disappoint. The film has everything that makes South Korean cinema so pleasurable—outstanding special effects, brilliant acting, imaginative storytelling, well-drawn, complex characters, and sharp social critique. Lee Byung-hun does an outstanding job modulating his character, making his character arc compelling and believable. Park Seo-jun and Park Bo-young are also great as a young couple whose lives and values are literally shaken up and turned upside down by the catastrophe. Despite its fantastical premise the movie never wavers in its examination of humanity under extreme duress.

CODA: This past week I had the fangirl pleasure of joining a zoom press conference for CONCRETE UTOPIA that featured Lee Byung-Hun and director Um Tae-hwa. It was fun to share the same virtual space as Lee, even if we didn’t directly interact. I tried to restrain my cyberstalker stanning as best I could but I’m not sure if I was entirely successful. CONCRETE UTOPIA is set to open in New York and Los Angeles on Dec. 8, and will go into wide release across North America the following weekend.

A More Constructive Use of Leisure Time: CAAMfest 2023 review

I had an interesting conversion recently with a friend who’s worked in the independent Asian American film community for a long time. He postulated that in some ways, Asian American film festivals have achieved everything they set out to do when they first started up back in the 1970s, which to him meant increasing the visibility and voices of Asian Americans in the US filmmaking landscape. In some ways I think he’s on target, with Everything Everywhere All At Once winning the Best Picture Oscar this year and streamers regularly programming Asian American content of all types. So where do we go from here? The 2023 CAAMfest shows all of the pros and cons of Asian American narrative plenitude.

CAAMfest opening night film, Joy Ride (dir. Adele Lim), is a great example of what happens when Asian American voices are mainstreamed—namely, that we’ve come far enough that we now have silly sex comedies from an Asian American perspective. I didn’t hate this movie and I did laugh in some parts but to my mind it was pretty predictable and pretty much lacking in emotional depth of any sort. The cast works hard and is charming and agreeable but all of their hard work can’t disguise the film’s sloppy story construction and gaping plot holes. Twenty years ago we all would’ve eaten this kind of movie up as progress but now that we’ve got a lot more options I feel less forgiving about this kind of simplistic execution. We don’t necessarily have to support representation for the sake of representation.

Similarly, Land of Gold (dir. Nardeep Khurmi), about a Sikh American long haul trucker who acquires a young Mexican American stowaway in his rig, is told in fairly conventional strokes. Currently airing on HBO Max, the film does feel like a made-for-TV movie in its standard narrative beats. Lead actor/director/writer Nardeep Khurmi is solid as the truck driver with some family issues to work out but I was very annoyed by child actor Caroline Valencia as the stowaway. She’s the kind of precocious and self-assured kid performer who feels like she’s been taking tap-dancing and voice lessons since she was wee and thus lacks any discernible authenticity as an actual child. But other reviewers have praised her performance and Land of Gold won both Best Narrative and the Audience Award at CAAMfest so what do I know? Again, twenty years ago this film would have been groundbreaking but now it seems less so to me. That said, I did love seeing the world of long-haul truckers and appreciated the small details, like the fact that every truck stop now serves Indian food and that there are homespun gurdwaras along the highway to allow the Sikh drivers to worship as needed.

More poetic and less formulaic is The Accidental Getaway Driver (dir. Sing J Lee), about an elderly Vietnamese driver for hire who gets caught up with three escaped convicts on the run in Southern California. The film does a good job connecting generational trauma with life on the lam, utilizing beautiful emotional dreamlike images and a gritty, dark mis en scene to create an unusual visual texture. Lead actor Hiệp Trần Nghĩa is great as Long, the driver who forms an unexpected bond with Tây (Dustin Nguyen), one of the convicts who is also Viet. Dustin Nguyen, who debuted as a teen star way back in the 1980s on 21 Jump Street, is excellent as the world-weary convict searching for a chosen family. He’s now sixty years old (!) and he’s come a long way from his heartthrob beginnings to become a sensitive and nuanced performer. Although at first it appears to be a crime film, with a noirish look and feel, the movie ultimately is about the relationships formed between the characters as they find solace and connections with each other.

Liquor Store Dreams is So Yun Um’s debut feature documentary and she guides the film with a sure hand. The doc is an expansion of her short film Liquor Store Babies (2014) and the longer version allows Um to elaborate on several of the themes she touched on in her short. Um updates the story of her Korean immigrant parent’s immigration experiences in the US to include pandemic era, expanding her scope to include a thread on reconciliations between black & Korean communities in Los Angeles. Her kind and smiley Dad is a healing presence throughout the film.

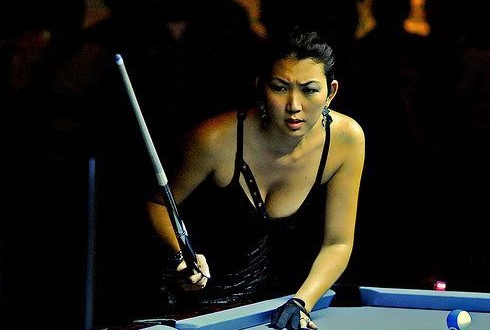

Another example of how Asian American voices have reached the mainstream, Jeanette Lee vs was produced by ESPN for their 30 for 30 series of profiles of sports figures. Director Ursula Liang brings a decidedly Asian American perspective to the story of Korean American Jeanette Lee, aka The Black Widow, who in the 1990s was one of the most famous and popular professional pool players in the world. Liang describes the many obstacles Lee faced to reach success in her sport including childhood scoliosis and a battle with cancer later in life, as well as the racism and misogyny she dealt with throughout her career. Liang also includes a moving interview with Lee’s elderly mother who describes her fear that her daughter will predecease her. By focusing not only on Lee’s professional journey but her struggles with white supremacy and patriarchy Liang injects a bit of Asian Americanism into a doc made for a general audience.

Twelve Days, Hong Kong director Aubrey Lam’s dramatic romance had no edge. The story, about a doormat wife and her asshole husband, is an AITA post come to life. It’s hard to feel much sympathy for either character since both the husband and wife are ciphers with no interior lives or motivations. With all of the interesting indie films coming out of Hong Kong these days it’s telling that this sleek, vacuous and politically inoffensive piece of aggravation is what the Hong Kong Film Council chose to showcase.

The uncatagorizable hybrid feature Starring Jerry As Himself (dir. Law Chen) was one of my favorite films from the festival but it’s impossible to explain this film’s appeal without spoiling it. Suffice to say I found it entirely satisfying and completely unpredictable, with dramatic music, solid performances, and good cinematography that makes good use of its Florida location, where nothing is as it seems and everything is fleeting and unreadable.

Wisdom Gone Wild, Rea Tajiri’s latest experimental documentary, is a lovely, thoughtful, and surprising portrait of Rea’s aging mom and her progression into dementia. The film shows dementia as a blessing that can become a new language and way of perceiving and combines a gorgeous sound design with home movies, contemporary footage, archival photos, a spare voiceover and Rea’s mom’s own gems of perception. I especially liked the evocative use of midcentury songs such as Smoke Gets In Your Eyes and other standards from the American songbook. The film is a brilliant example of how to say more with less and how to have faith in your viewers’ ability to discern meaning without excessive explanation. To my mind it is really the best thing in this year’s festival. Wisdom Gone Wild’s freeform, improvisational structure, guided expertly by Rea’s accomplished, confident hand, results in a film that’s not afraid to take risks and make bold and surprising choices.

Rea Tajiri’s documentary is the kind of film that I want to see from Asian American cinema in the 21st century, and not just horny road trip movies. I hope that we don’t simply aspire to insert Asian American characters into the same old genre movies. I want to be confounded and surprised by Asian American movies, not shown the same stories we’ve seen before. Otherwise we may find Asian American filmmaking to be obsolete and irrelevant, as it becomes just another cog in the commercial moviemaking machine.

Summum bonum: 2023 SFFILM festival

The 2023 edition of the SFFILM Festival took place this year in mid-April , with in person screenings in San Francisco and the East Bay. This was a streamlined version of the festival, with just two or three screenings of most films and taking place at just three venues, the Castro and CGV Cinemas in San Francisco and BAM/PFA in Berkeley, plus one show on Opening Night at the Grand Lake in Oakland. The number of programs was down from 105 in 2023 and 130 in 2022 to 96 this year. It was a bit trickier catching films but I managed to see three excellent non-fiction films, each of which challenged documentary filmmaking conventions.

With King Coal, director Elaine McMillion Sheldon creates a poetic elegy to Appalachia, at once dreamlike and hard as nails. The film is a stylistic departure from her earlier verite-style films Heroin(e) and Recovery Boys, both of which looked at the opioid crisis in the region where she was born and raised. King Coal blends observational filmmaking with several staged, unscripted sequences featuring two young girls and was shot in the heart of the heartland where coal mining was the backbone of the economy for decades. The film is a fascinating hybrid that sympathetically portrays the plight of a region that has long been exploited for its natural resources, at great human cost. King Coal does make the case that white working class people are victims of capitalism, which may skirt a bit too close to arguments about “economic anxiety,” ignoring the presence of white privilege. But McMillion Sheldon’s cinematic vision is so compelling and so lyrically realized that in this case I’m willing to overlook a little bit of societal myopia.

In The Tuba Thieves director Alison O’Daniel, who is hard of hearing, creates a film that questions the presence and absence of sound from the perspective of mostly Deaf characters. As might be expected from its title, the film takes as a jumping off point a series of thefts of tubas from Los Angeles area schools over the span of a few years, but its scope is wide-ranging and only tangentially touches on those events. The Tuba Thieves consists of several short vignettes that look at sound and silence, including a dramatization of the premiere of John Cage’s 4’33” to a somewhat bemused audience in upstate New York, archival footage of the organizers of Prince’s 1984 concert at Gallaudet University (the famous institution for Deaf and hard of hearing students), a recreation of a concert at the legendary San Francisco punk venue The Deaf Club, and parallel narrative threads focusing respectively on a Deaf drummer and a hearing teenager in a marching band whose tubas are among the stolen items referenced in the film’s title. O’Daniels’ film makes creative use of open captioning, creating poetically descriptive titles that enhance and embellish the sounds and dialog in the film.

Another particularly telling element is the recurring discussion of sonic booms, which are created when an aircraft travels faster than the speed of sound. Instead of including the actual sound of the phenomenon, O’Daniels instead shows pictures of planes breaking the sound barrier. In these ways the film privileges the perceptions and points of view of the Deaf and hard of hearing community. The result is a fascinating take that draws attention to what most hearing people take for granted—the way that sound interacts with the environment and with daily life.

Milisuthando, Milisuthando Bongela’s semi-autobiographical eponymous essay film, is a long and dense look at South Africa just before and just following the end of apartheid. Comprised of much archival and broadcast footage, personal reminiscences, some sit-down interviews, and the filmmaker’s own astute observations in voiceover, the film explores South Africa’s fraught and convoluted history of race relations. Milisuthando examines a multitude of topics including Nelson Mandela, white guilt and white privilege, school integration, and the perils and pleasures of interracial friendships, among many others. Bongela allows many passages in her film to run a bit longer than may be comfortable to viewers accustomed to the rapid pace of most commercial films, a technique that works to good effect in both stimulating introspection and creating discomfort. It’s a good film and one that I plan to revisit to tease out more of its nuances.

NOTE: SFFILM had most of its San Francisco screenings at CGV Cinemas (formerly the AMC 14), an outpost of the huge South Korean cinema chain, which opened in 2021 in the middle of the pandemic. The theater was my go-to whenever I wanted to see a blockbuster Hollywood or Korean movie all by myself and the handful of times I saw a film there there were usually about a half-dozen other customers in attendance. Once or twice I was the only person in the entire theater (and possibly in the entire multiplex) and for some reason the venue either didn’t have or never turned on the air-con, which made it much less appealing to go to. For whatever reason, business has continued to not be good and in late February CGV announced that it would be closing the San Francisco branch as of March 1, with sporadic events such as SFFILM continuing in the space. With the future of the Castro Theater still in limbo and the closure of the last movie theater in downtown Berkeley in January 2023, big-screen moviegoing in the Bay may be very limited in the future.

Deeper Into Movies: San Francisco Jewish Film Festival 42

The San Francisco Jewish Film Festival just completed its 2022 run, which marked a return to in-person programming after two pandemic years during which the festival was almost exclusively online. As usual the programming spanned a wide range of genres and films.

The festival opened with the Israeli narrative, Karaoke, which looks at a middle-aged Tel Aviv married couple whose lives are upended when a swinging bachelor moves into the penthouse of their apartment building. The film is a subtle study of a seemingly banal and ordinary couple, unobtrusively revealing its story with restraint and insight. There’s a whisper of queerness that’s too understated to be called a twist but the information adds complexity to the overall effect of the film.

Another narrative, Haute Couture, is much more conventional and much less successful in its storytelling. Although beautifully shot and nicely acted, the film lacks much depth in its characterizations and is at its core deeply problematic. The story follows Esther, a seamstress in the Dior fashion house who meets Jade, a streetwise young French Arab woman, and takes her under her wing by giving her an apprenticeship at Dior. Though on the surface Haute Couture seems forward-looking by including actual Arab characters in a film set in France, most of the characters’ various cultural identities are plot devices that are quickly skimmed over, including a token trans character who primarily serves as window dressing. Even Esther’s Jewish identity is quickly introduced but ultimately irrelevant to her actions. Esther also utters some pretty egregiously racist comments, but the film uses the old trope of including an even more racist character to make Esther seem less offensive by comparison. Structurally, the movie races from one contrived plot point to the next, and Jade’s worshipful acceptance of her “rescue” from her ghetto roots reeks of white saviorism.

More successful were several documentary and essay film selections in the festival. JFF Director of Programming Jay Rosenblatt is a noted experimental filmmaker (his most recent accolade being an Academy Award nomination for Best Short Documentary) so it’s no surprise that the festival included films that depart from the standard narrative or documentary fare.

Oakland resident Pratibha Parmar’s My Name Is Andrea explores the life and legacy of radical feminist theorist Andrea Dworkin. Dworkin’s a controversial figure and has been reduced to a cartoon character over the years so revisting her work is a revelation, and the film showcases her charismatic presence and her unrelenting examinations of misogyny in contemporary US culture. Parmar re-enacts key moments in Dworkin’s life as played by several different actors including Ashley Judd and Christine Lahti, interspersed with archival footage of Dworkin herself in all her astute, well-spoken, and passionate glory. The film is visceral, gripping and ultimately brilliant and makes a strong case for the continued relevance of Dworkin’s perspective and theories on violence against women—she ain’t wrong, people.

A more conventional documentary, Bernstein’s Wall (dir. Douglas Tirola) looks at the life of legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein as told almost exclusively in Bernstein’s own words. The film is archival archival archival, with Tirola taking a trove of footage and shaping it into a cohesive, engaging narrative. Although Bernstein himself never spoke publicly about his queerness, the film also includes excerpts from private missives between various intimates including mentor Aaron Copeland, Bernstein’s siblings, and his depressed wife, who describes herself as “the governess.” Nicely done and eminently watchable, the movie paints a respectful picture of Bernstein as a driven, ambitious, and somewhat frustrated artist whose consuming career may not have been very kind to some of the people closest to him.

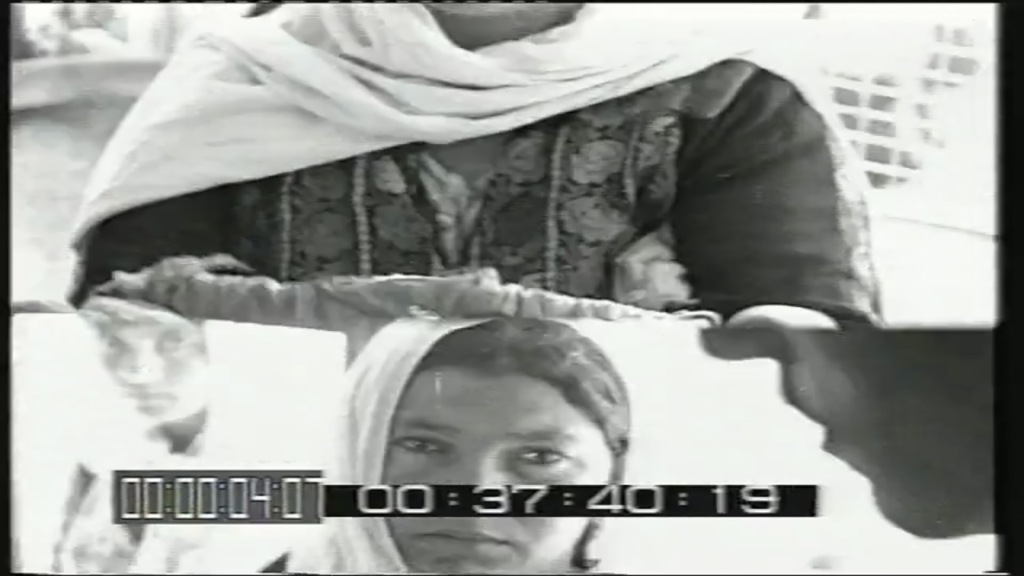

In A Reel War: Shalal, director Karnit Mandel describes her experience trying to track down the whereabouts of the lost film archives of the Palestinian Liberation Organization that were seized by Israel during the 1982 Lebanon war. This incisive essay film emphasizes the importance of images in cultural memory and the way that cultural erasure and forced amnesia act as a forms of imperialism.

Babi Yar: Context, focuses on the genocide of the Jews in Ukraine during World War II. Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa (winner of the JFF Freedom of Expression Award) makes the case that residents of Ukraine were complicit in one of the most infamous Nazi atrocities, the 1941 massacre of nearly 34,000 Jews who over the course of two days were shot and buried in the Babi Yar ravine near the city of Kyev. The film, which is completely without narration, tells its story exclusively through archival footage and a reconstructed sound design. Although the evidence is circumstantial, Loznitsa deftly makes the argument for Ukranian complicity through footage such as the hero’s welcome that Nazi officials recieved in Ukraine and cheerful Ukranian women and children digging mysterious trenches. These are later followed by chilling testimony of both Jewish survivors and German perpetrators of the executions who described the massive scale of death. Although the film skirts toward atrocity porn, it nonetheless makes a cogent argument for the Ukranian collaboration in the “holocaust by bullets” that occurred at Babi Yar.

Save It For Later: 2021 SFFILM Festival

Before COVID-19 upended our lives I was a big-screen film snob. Living in San Francisco, with its year-round calendar of world-class film festivals as well as rep theaters such as the Pacific Film Archive, the Roxie, and the Castro, it was easy to consume a steady diet of a huge range of cinematic treats solely in movie theaters. All of that changed with the pandemic, and as we enter the second year of the age of coronavirus pretty much all film festivals have shifted online. The SFFILM Festival’s 2021 edition was no exception, and as usual it presented a broad spectrum of international programming. Though my time was very impacted I was able to catch several outstanding movies.

I really enjoyed South Korean director Lee Ran-hee’s impressive debut feature, A Leave, which is a small slice of life about an out-of-work laborer who’s been suing his former employer for the past five years. While manning a protest station in Seoul with a few other diligent souls his daughters who are living apart from him in a Seoul exoburb have entered their teen years and grown up without him. When he returns home for a brief week he cleans the house, fixes the sink, does itinerant labor at a small furniture-making shop and gradually re-enters his family’s life. But his duty as a protestor calls him back to Seoul despite his older daughter’s pleas for him to abandon his quixotic cause. Gritty and realistic, this humanistic portrait shows the crushing weight of workers who live hand to mouth in a neoliberal economy.

Also outstanding was Iranian director Firouzeh Khosrovani’s personal documentary, Radiograph of A Family. Tracing her parents’ relationship starting in the 1960s from their meeting in Switzerland, when her father, who was educated in the West, met her mother, who was younger than her husband, more conservative and more religious. The film follows their lives together in both Europe and Iran, where her mother became a teacher and an activist during the Islamic revolution. Using archival footage and photographs, home movies, and fictional and non-fictional dialog Khosrovani creates a delicate, fascinating portrait of a family caught up in great historical events.

Roberto Salinas’ unobtrusive observational documentary Cuban Dancer follows aspiring ballet dancer Alexis Valdes from age 15 from his home in Cuba to the US where he trains in Florida at a private dance academy. The film includes some failures and some successes as Alexis adjusts to his life in a very different environment from the nurturing world he left behind in Cuba, as he gradually learns English and makes friends in the US. This is the third documentary I’ve seen about Cuban performing artists this year, the other two being the outstanding Los Hermanos/The Brothers and the somewhat more pedestrian but still enjoyable Soy Cubana. Cuban Dancer falls somewhere in between the two of them, as it lacks the cultural and political context of Los Hermanos but has a sturdier and more compelling narrative than Soy Cubana. Postscript: Alexis Valdes went on to attend the San Francisco Ballet School and is now an apprentice dancer in the company.

The festival also included several mid-length films with running times between 30-50 minutes. Created as promotional material for his album of the same name, hip hop artist Topaz Jones’ essay film Don’t Go Tellin’ Your Momma is structured around replicating the Black ABCs, the iconic flashcards created in the 1970s by a pair of Black educators in Chicago in an attempt to center African American culture. Jones’ film similarly focuses on the Black experience, blending archival footage, staged vignettes, and interviews with Black intellectuals. Tiffany Hsiung’s mid-length documentary, Sing Me A Lullaby, follows her mother Ru Wen’s journey back to Taiwan to find her own mother who she hasn’t seen since she was five years old. This emotional doc captures the sense of loss and longing among exiles as it traces Ru Wen’s poignant story.

The last film I managed to see was Chloé Mazlo’s narrative feature, Skies of Lebanon. Charming and inventive, the film follows the lives of Joseph, a Lebanese rocket scientist and Alice, a Swiss expat who moves to Lebanon in the 1950s to escape her oppressive family life. Joseph and Alice fall in love and marry, raising their daughter in 1960s Lebanon among a large and affectionate family. Beginning in 1975, the long destruction of the Lebanese Civil War takes its toll and gradually most of Alice and Joseph’s extended family flees Beirut, including her beloved daughter Mona. Like Radiograph of A Family, this film looks at the effect of history’s upheavals on everyday individuals. Director Mazlo is a French Lebanese animator and artist and Skies of Lebanon, her first feature film, uses claymation, subtle CGI, theatrical devices, magic realism, and surrealism, as well as some really beautiful, economical storytelling, to spin its engaging tale.

Though I appreciate the ease of viewing that comes with streaming films at home on my laptop it’s still no substitute for watching movies in a theater with a crowd of like-minded cineastes. Still, until it’s safe for us all to go back to the cinema, I appreciate SFFILM’s thoughtful and varied programming. It’s a balm in a year of deprivation.

Talent Is An Asset: 2021 SXSW Online, part one: Film Festival

When the COVID-19 tsunami hit the U.S. back in March 2020 Austin’s SXSW film and music festival was one of its first casualties. The entire event was dependent on live performances and screenings and with the country going into lockdown there was no chance it could happen that year, so the whole shebang was cancelled outright. But subsequent film festivals began pivoting to fully online and this year SXSW was an entirely online event, including films, music, conference panels, and networking. Luckily for me, this format also gave me the chance to attend my first SXSW and I ingested a huge amount of content from the comfort of my own home. Because of the sheer volume of performances that I consumed Imma split my review into the film side and the music side, starting with the cinematic treats I watched.

The festival included two documentaries about influential and innovative pop stars that have flown somewhat under the mainstream radar. Poly Styrene: I Am A Cliche looked at the life of the leader and vocalist of the legendary UK punk band X-Ray Spex. As a baby punk back in the 80s one of the best things about early punk and new wave was the presence of women of color such as Pearl E. Gates, Pauline Black from Selecter, and Poly Styrene. Poly was not only a punk icon but also a woman of color icon and it was great for me to have a Black woman role model who could belt it out with the best of them. The film traces Poly’s meteoric brilliance as the leader of X-Ray Spex at age 19, as well as her struggles with mental illness and her involvement with the Hare Krishna sect later in life. Told from the POV of her daughter Celeste Bell, who is credited as the film’s co-writer and co-director, the film interweaves her narration with a plethora of archival footage and photos. As a mixed-heritage child (or half-caste, the term that was in common usage at the time) raised by a single mother in 1960s Britain, Poly (nee Marianne Joan Elliott-Said) faced a fair amount of casual racism and ostracization. The film shows the range of Poly’s artistic endeavors outside of her singing career, including several passages from her journals (read by Ruth Negga), as well as her unique and idiosyncratic fashion sense which she developed in her teens and which she highlighted in her years as the face of X-Ray Spex. Celeste Bell’s somewhat mournful narration adds a gravitas to the film as she searches for the truth of her mother’s life and legacy. But throughout it all the story is driven by the power of Poly’s clarion voice and poetic vision.

The Sparks Brothers, directed by Edgar Wright (Shaun of the Dead; Baby Driver) explores the iconic cult band Sparks, utilizing a ton of archival footage, interviews with the band’s many admirers including Bjork, Giorgio Morodor, Todd Rundgren, and many more, accompanied by Sparks’ excellent and eclectic pop music. Emulating the cheeky and off-kilter attitude of its subjects, the film follows Russell and Ron Mael, the two brothers who founded Sparks, from their childhood in Southern California through their long and winding musical career. The film captures the brothers’ sardonic style as seemingly British invasion cult darlings (belied by their SoCal roots) with their first hit in the UK, This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us, through their survival in the fickle world of rock music in the more than four decades since. I’ve always been a fan of Sparks and their unique and twisted pop stylings, led by Russell Mael’s dramatic and operatic high tenor and Ron Mael’s sophisticated keyboards and songwriting, so this movie was a fascinating look at their career trajectory. Always ahead of the pop music curve, the film demonstrates the Mael brothers’ influence on disco, new wave, EDM, synth pop and much more. It also shows how their highly visual and cinematic presentation, with the more traditionally rock styled Russell contrasting with Ron’s odd Hitler/Chaplin persona, made them a perfect fit for the MTV era, when they scored their new wave hits The Number One Song In Heaven and Beat The Clock. Throughout the film their wit and intelligence shine through.

Two other docs in the festival looked at politics and current events. The United States vs. Reality Winner is a procedural agitprop doc ala CitizenFour, Laura Poitras’ Oscar-winning film about Edward Snowden, another famous whistleblower. Snowden even makes an appearance in this film, as do several other commentators who contextualize Winner’s case. The film follows Winner’s mom as she tries to get a fair trial for her daughter who has had the book thrown at her for exposing Russia’s influence on the 2016 US presidential elections. As with CitizenFour and other films of its ilk, The United States vs. Reality Winner has a definite opinion and relentlessly pursues it.

In contrast, Nanfu Wang’s documentary In The Same Breath, which looks at the beginnings of the coronavirus pandemic in Wuhan and in the US, is all about doubt and questioning and its lack of clear answers reflects the confusing times we’re still enmeshed in.Included in the film is some stunning security camera footage of the very earliest days of the pandemic in Wuhan that shows how quickly the virus spread and how unprepared health officials were in their initial response. The film beautifully expresses the ambiguity and uncertainty of the COVID-19 era while sounding a warning about the inherent untrustworthiness of governments both in China and the US.

The Fabulous Filipino Brothers, Dante Basco’s directorial debut, is in some ways a spiritual successor to the iconic 2001 Asian American film The Debut. That movie, which starred Dante and also included appearances by his three brothers Dion, Derek, and Darion and sister Arianna, is much beloved in the Filipino American community for its lighthearted look at FilAm culture, traditions, and identity. The Fabulous Filipino Brothers is is similarly Filipino AF and it was interesting to watch more than 20 years after The Debut made its premiere. It’s set in Pittsburg, CA and loosely revolves around an upcoming wedding in a big-ass Filipino family. Many Bascos were involved in the making of this film, including the four Basco brothers in lead roles, with narration by Arianna. The film is a bit rough around the edges and never transcends its sitcom aesthetic, but all four brothers are talented performers and each does well in their respective vignettes. Their agile comic timing and ability to hold the screen makes me wonder why their careers didn’t take off after the success of The Debut, but as usual the answer is probably racism. A humorous side note: one of the characters is in a depressive funk which he deals with by composing atonal electronic music that sounds a bit like some of the stuff I heard at the SXSW music festival.

I also caught a couple excellent short films of the many that were included in the festival. Águilas, by Kristy Guevara-Flanagan and Maite Zubiaurre, follows a group of volunteers who scour the Sonoran desert near the Arizona border looking for the remains of those who have died attempting to migrate on foot to the US. A short, intense look at those who carry out this grim duty, the film is suffused with empathy for the people who have lost their lives traveling from their home countries as well as those who search for their last remains.

Red Taxi, by an anonymous director, utilizes interviews with cab drivers on both sides of the Hong Kong-Shenzen border that were shot during the massive 2019 Hong Kong protests. The short documentary provides an interesting contrast between the pragmatic hopefulness of the Hong Kong cabbies and their PRC counterparts, who for the most part don’t have much sympathy for people of Hong Kong who were speaking out against the government at the time. It’s an interesting snapshot of the times and shows the divide in opinion on either side of the border without judging or taking sides. It’s also telling that the director has chosen to be anonymous, reflecting fears of the oppressive new National Security Law in Hong Kong that effectively punishes residents for speaking out in any way against the Beijing regime.

Next up: Part two, in which I attempt to encapsulate the huge number of international performers I saw on the music side of this year’s SXSW.

Ride The Lightening: 2019 San Francisco Documentary Festival

Round two of my film festival travels from the past few months. Although it’s been running annually since 2001, for some reason I’ve never attended San Francisco Documentary Festival before, due in part to the general glut of film festivals of all stripes in San Francisco. DocFest, as it’s more popularly known, is one of several organized by the San Francisco IndieFest throughout the year—in addition to this and the original IndieFest the others being the horror-focused fest Another Hole In The Head and the SF Indie Shorts Festival.

Opening night film Cassandro the Exotico! (dir. Marie Losier) focused on the life and career of the openly gay lucha libre wrestler Saúl Armendáriz, better known by his ring name Cassandro, who was born and raised in El Paso. The film follows Cassandro as he considers winding down his career following nearly 40 years and many injuries after his start in the ring at age 15. The film frankly discusses Cassandro’s struggle with addiction, pain, and facing homophobia and he is a fascinating and engaging main character. Losier shot the film on 16mm and the movie’s rough, anti-slick aesthetic perfectly meshes with Cassandro’s gritty backstory. At times there is a visible hair in the gate, which at first is a distraction but then becomes part of the film’s mis en scene. After seeing way too many formulaic PBS-style docs at some of the film festivals I’ve been screening at it’s nice to see something with a looser, more original look and feel.

17 blocks (dir. Davy Rothbart) is verité-style doc following the Sanford-Durants, an African American family who live just seventeen blocks from the US Senate building in Washington DC. Rothbart beautifully structures more than 20 years of footage, shot in large part by the family itself, into a moving portrait of survival and strength. Although the film is powerful and effective and advocates for stronger gun control laws, it only lightly touches on some of the broader structural causes for the Sanford-Durant family’s problems including toxic masculinity, racism, and white supremacy. Despite the reference to the US Senate in the film’s title the film is oddly apolitical and the family’s problems exist in a bit of a vacuum. I would like to have seen a bit more context for the problems the family faces.

Framing DeLorean (dirs. Don Argott and Sheena Joyce) is a slick and clever re-presentation of the case of automobile impresario John Delorean, with documentary interview footage interspersed with reenactments of key moments in Delorean’s career as played by Alec Baldwin and other actors. It’s sort of high-concept meta but it works, and the film has just the right amount of irreverence to propel the story.

Murder in the Front Row: The Bay Area Thrash Metal Story (dir. Adam Dubin) a bit rough around the edges but it’s full of the DIY energy of the 1980s East Bay thrash scene that spawned metal legends such as Metallica, Megadeth, Death Angel, Slayer, and Exodus, among others. The film’s structure wanders a bit and to the casual observer less familiar to the various personalities the interviewees may hard to keep track of as they move rapidly from band to band. The film also glosses over some of the darker elements of the story such as Dave Mustaine’s substance abuse problems as one of the factors for his dismissal from Metallica and the random property destruction recalled by many of the interviewees (which I understand is because rock and roll, but come on). The film never escapes being fannish and unlike the best music docs doesn’t go into some of the more sociological reasons for the popularity of the genre. But as a former Bay Area punk it was fun for me to watch since the thrash scene at the time ran in parallel circles to the hardcore scene that I inhabited, and the film captures a lot of the anarchic energy of the time.

In contrast to the nihilistic feel of Murder In the Front Row, I Want My MTV (dirs. Tyler Measom and Patrick Waldrop) is a slick, fast-paced, fun and kicky doc that hits all the high points of the history of the groundbreaking cable channel, including hair metal, Michael Jackson, Madonna, race, misogyny, and even a touch of whiteness. The film explores a time when rock was still king, now more than 35 years ago, connecting the Monkees, Top of the Pops, and A Hard Day’s Night, although it doesn’t touch on earlier other antecedents like Hollywood musicals. Very professionally executed, the film moves from MTV’s humble and somewhat chaotic beginnings to its utter dominance in the late 80s, demonstrating how music videos at the time affected the commercial pop music industry, and concludes with youtube effectively ending MTV’s symbiotic relationship with the music videos it engendered. The film is pretty focused on black and white America, with only a tiny glimpse of Psy at the very end, and lacks contextualization, relying on personal anecdotes to tell its story. Not that the movie has to be a scholarly treatise but there’s been a ton of critical and cultural analysis has been done on MTV and its effects that the movie doesn’t really address. But it’s a fun ride nonetheless and the movie is loaded with crowd-pleasing archival clips.

Motherload, Liz Canning’s affectionate tribute to the world of cargo bikes, delves into the appeal of bicycle-based transportation and how it could change the world. Canning effectively weaves her personal experiences of discovering the glories of bike transport into a broader story of the growth of bicycles as a means of combatting climate change and other environmental crises and while a tad utopic, the film should be very popular with the biking crowd.

Long Dark Road: 2019 Noir City film festival

Party Time, Pickup On South Street, 1953

The 2019 edition of the Noir City film festival just finished another excellent run and there was a party atmosphere for the 10-day festival as the Castro Theater hosted full houses for almost every show. As usual Noir City had value-added features including live music in between some shows, screenings of rare clips and trailers, and informative and edifying introductions by Noir City founder Eddie Muller and other knowledgable film noir geeks/authors. The movies I attended were uniformly good, but a few stood out due to the significant combination of a great cast, a strong script, and excellent direction.

Some of the festival’s offerings fell a bit short on one of the three key elements above, making for less than satisfying results. For instance, legendary director Michael Curtiz (Casablanca; Mildred Pierce) helmed The Scarlet Hour (1956) with a sure hand, and the script is classic noir, about a femme fatale and her hapless sap of a boytoy who are involved in a jewel heist. But rookie actresss Carol Omhart isn’t quite up to scratch in the lead role and despite its other strong elements the film falters on her uneven performance. Conversely, The File On Thelma Jordan (1950) includes an excellent performance from Barbara Stanwyck and moody and evocative direction by Robert Siodmak but the script’s improbable plot twists diminish the film’s overall impact.

Struggling, Nightfall, 1957

Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall (1957) is a much more successful endeavor. Although not possessing the mournful beauty of his classic noir Out of the Past, Nightfall still showed Tourneur’s strong directorial touch. The film’s two thugs, played by Brian Keith and Rudy Bond, feel truly menacing and Aldo Ray as the protagonist on the run conveys a strong sense of a man struggling to keep his bearings in the shifting sands of noir-world danger. A very young Anne Bancroft is Ray’s love interest and her performance displays a strength and gravity beyond her years. The film has just the right touch of fatalistic peril and dread to keep the viewer engaged.

Complex, Pickup On South Street, 1953

One of my favorite films of all time, Pickup On South Street (1953), was part of a trio of movies directed by Sam Fuller in this year’s festival, and it fully demonstrates a film firing on all cylinders, with acting, script, and directing all top-notch. Fuller’s kinetic directorial style and his intense, fast-paced script brilliantly complement Richard Widmark and Jean Peters’ performances as streetwise characters who are constantly maneuvering to survive. Thelma Ritter contributes a stellar performance as an aging stool pigeon, delivering a complex and emotional turn that forms the moral center of the movie.

Sultry, The Crimson Kimono, 1957

The festival also screened Fuller’s 1957 film The Crimson Kimono, which is notable for including a Japanese American character, Joe Kojaku (played with sultry subtlety by the doe-eyed James Shigeta), in a romantic lead. The film also includes a sympathetic and mostly Orientalist-free representation of the Los Angeles JA community with Nisei characters who speak in unaccented English and who are human beings instead of exotic caricatures. The film falls a bit short, however, in its analysis of race relations as it suggests that Joe’s experiences with racist microaggressions are a figment of his imagination. SPOILER: He does get the girl, however, which for mid-1950s America was pretty revolutionary.

Tense, Odds Against Tomorrow, 1959

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), a tense crime thriller produced by and starring Harry Belafonte, also possesses the magic combination of script, cast, and direction. The film shows a darker side to Belafonte’s usual upbeat persona as he plays Johnny, a nightclub singer facing dire straits due to his gambling addiction. After loan shark enforcers threaten his family with harm Johnny teams up with a couple of other shady characters including Earl, a racist from Oklahoma played by Robert Ryan, and David (Ed Begley), a fallen-from-grace cop. They three attempt to pull off a risky bank heist but the meat of the story is the strong character development of both Johnny and Earl. Director Robert Wise (West Side Story; The Sand Pebbles) delves into both characters’ personal lives to give weight and heft to what’s at stake for the two. As a result the film’s climax and conclusion are exceptionally tense and gripping. Also, unlike The Crimson Kimono, racism doesn’t get a pass in this film SPOILER and in fact Earl’s flagrant bigotry is a key culprit in the failure of the heist. END SPOILER Bonus points for supporting roles from Shelly Winters as Earl’s long-suffering girlfriend and Gloria Grahame as the sexy neighbor upstairs, as well as for the excellent score by John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The festival concluded with a pair of hard-boiled films from 1961. Sam Fuller’s third installation in this year’s festival, Underworld USA, is a bleak little number full of vengeance, double-crosses, and grudges. Cliff Robertson snarls his way through the film as a safecracker out to get the thugs who killed his dad some twenty years prior. With almost no redeeming characters the film is an existential ode to the shady side of life, where the only motivations are revenge and survival.

Twisted, Blast of Silence, 1961

The festival closed with the excellent and underappreciated Blast of Silence, a low-budget gem directed with a stylish and jaded eye by Allen Baron. Baron also stars as Frankie Bono, a creepy hitman who presages Travis Bickle in his angst-ridden interior monolog and his twisted, affectless approach to killing. The film follows Frankie as he plots his next hit and depicts his sad and stilted attempts to make meaningful human contact beyond his gruesome professional responsibilities. Bleak, hard-boiled, and grim, and set in the dead of winter between Christmas and New Year’s day, Blast of Silence is like an icy slap of cold air on a winter’s day.

Recent Comments